Manipur, lovingly called the Sanaleipak or the land of gold, had various clans and tribes rooted in her soil. The seven major clans Khábá, Cenglei, Luwáng, Khuman, Moiráng, Angom and Ningthoujá integrated to form the Meiteis. The hill people like the Nagas, Kuki-Chins and the Mizos added palpably to the ethnic culture of this state. The culture of the people at large is observed clearly in the traditional ethnic festival the Laiharaoba.

Indigenous festival of Manipur

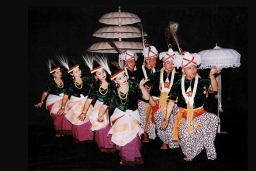

A dance sequence of Laiharaoba. Photo courtesy Dr Thoiba Singh.

A dance sequence of Laiharaoba. Photo courtesy Dr Thoiba Singh.Many scholars have translated the word láiharáobá into English. But the most commonly accepted one is Shakespeare’s phrase "the pleasing of the god" (in Parrat & Parrat, 1997, p. 189) with a modification to "the pleasing of the gods" (ibid). In this the gods are worshipped and are pleased by the participants of láiharáobá. Again there is another interpretation of láiharáobá as "the merrymaking of gods". In this case the participants take the role of gods and are involved in merrymaking.

The láiharáobá is the original source of dance and music, rites and ritual, indigenous games and primitive life of Manipur. In short it may be a vestige totemistic belief and the culture of Meitei is derived from the Láiharaoba. (Singh, R. K. Achouba 1991-92, p. 10)

One cannot trace the origin of láiharáobá in the history of Manipur. It is said that the láiharaobá was first performed at Koubru Hill and the then performance called the Kaubru Haraorol was a shorter version of the present láiharaoba and it did not contain certain sequences like lamthekpa, kangleithakpa etc. Later on at Nongmeijam Hill, kangleithakpa and other rituals were included and they represented a marriage of the lái (god) khoiriphaba. The Pundit scholar Atombapu Sharma (1951, p. 4) is of the opinion that:

The root ‘Harao’ in Manipuri is the meaning of the word ‘Harsa’ (merrymaking) in Hindi. It is formed by suffixing ‘Ba’ of Krt in the Middle voice and it means Sannaba that is to play. ‘Láiharaoba’ when expanded stands as Láigi=of God+haraoba=playing, and it is in the Sasthi Tatpurusa Samasa (compound). The antecedent word ‘Lái’ of such a compound is the name of God. The Manipuris at times used to worship God as symbols of sex. The Meiteis think the union of the Earth and the Heaven to be the Samba Murti i.e. the first object of meditation of the Yogi-s (meditating personalities). In this way they worshipped the Samba-Murti to be the union of father and mother and thought the union to be the sexual union generating the whole universe.

Sanskritisation and Manipur

A study of the history of Manipur reveals that Vaishnavism 1 started establishing itself from the time of King Kyamba. Vaishnava preachers from Tripura, West Bengal, Mathura and Orissa came to Manipur during Cherairongba's time. One of the distinguished preachers was Rai Banamali, who arrived in 1703. Cherairongba offered him land, house and constructed a Radha-Krishna temple. He was accepted as the guru (master) of the king when Cherairongba was initiated to Vaishnavism.

The social and cultural life of Manipur registered changes following the inflow of this religion. Delving into the characteristics of these changes I would argue that it was not an isolated stream of change. This process of transformation happened at many places in the mainstream of Indian social life through the ages. Social reformers have named it the Sanskritisation Process. Professor S. K. Chatterjee first used the word Sanskritisation in the year 1950. In introducing the word Sanskritisation, Chatterjee (1974, p. 42) comments:

The Progressive Sanskritisation of the various pre-Aryan or non-Aryan peoples in their culture, their outlook and their ways of life, form the keynote of India through the ages. And in the course of this Sanskritisation the affected people also brought their own spiritual and material milieus to bear upon the Sanskrit and 'Sanskritik' culture which they were adopting and thus helped modify and to enrich it in their own circles.

M.N Srinivas (1989, p. 56) opines on Sanskritisation thus:

Sanskritisation may be briefly defined as the process by which a ‘low’ caste or tribe or other group over [sic] the customs, ritual, beliefs, ideology and style of life of a high and in particular, a twice-born (dvija) caste ... It normally presupposes either an improvement in the economic or political position of the group concerned or a higher group consciousness resulting from the contact with a source of the ‘Great Tradition’ of Hinduism such as a pilgrim centre or a monastery or a proselytizing sect.

He continues by remarking:

In the case of group external to Hinduism such as a tribe or immigrant ethnic body, Sanskritisation resulted in drawing in into the Hindu fold, which necessarily involved its becoming a caste having regular relations with other local castes. (ibid)

On a closer inspection of the Sanskritisation process in Manipur we find that the process brought about a unification of Manipuri social life with the mainstream Hindu society based on caste distinction. The system of varna 2 worship of the Vedic deities and Aryan religion rituals entered Manipuri social life as the people embraced Vaishnavism in the leadership of the King. The complete assimilation of Manipuri civilisation into the stream of ancient Aryan and Brahmin civilisation became possible.

The Brahmin priests brought the Meitei Yek-Salai under the Hindu gotra 3 system. The Hinduised clans or Gotra names were concocted by linguistic alteration in the following manner: Ningthouja-Sandilya, Angom-Goutam, Moirang-Atriya Angira, Luwang-Kashyap, Khuman-Madhukalya, Khaba Ngaba-Madhukalya and Bharadwaj, Chenglei-Vasishta. (Saha, 1994, p. 107).

It may be noticed that, as in other places, the promoters of this process of Sanskritisation were mainly persons belonging to the ruling classes of Manipur. Explaining the reason for this Srinivas (1989, p. 63) says:

Sooner or later, power has to be translated into authority, and it was precisely in this situation that Sanskritisation was important. He who became chief of king had to become a kshatrya whatever his origins. In those areas where a bardic caste existed the chief was provided with a genealogy linking him to a well-known kshatriya lineage and even to the sun or the moon. The indispensability of Brahmins is pointedly seen in the fact that in areas where there was no established Brahmin caste the chief had either to import them from outside, offering them gifts of land and other inducements, he even had to create Brahmins out of some ambitious local group.

Many have opined on the reason of the patronage of the Brahmins by the kings.

On their side the Brahmins had a positive approach to anyone who wielded power. Brahmins were predisposed to reverence power and they helped to legitimize power into authority. They performed the essential Vedic rites, which proclaimed the kingly status of the actual wielder of power and they sang his praises in Sanskrit. The rulers and his castes were in turn patent sources of Sanskritisation both in the support and patronage they gave to priestly and learned Brahmins and in providing a particulars model of Sanskritized life-style to those who came under their influence. (Saha, 1994, p. 63)

In Manipur it has been observed that the rulers and their patronised Brahmins were always inter-supportive of each other. The rulers would look after the total worldly welfare of the Brahmins and proffer social dignity on them. The Brahmins in turn would introduce new trends in literature and culture and actively co-operate to satisfy the desires of the rulers. Each and every characteristic cited by Srinivas as an 'instrument' in the process of Sanskritisation is found in Manipur.

We find the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Puranas play an important role in the process of Sanskritisation. These have helped Sanskritic Hinduism or the ancient Hinduism to smoothly enter into an alien society and culture. These epics have not only spread the tales of the Hindu gods and goddesses and related their greatness; they have also revealed the main viewpoints of Indian philosophy. However, their chief contribution is that they have been the medium of forming a common platform for the entire country. V. Raghavan (1956, p. 497) commenting on this aspect has said:

In religious dogma and cult puranas, agamas and tantras show how the great tradition absorbed different local cults and made a pattern and system out of the heterogeneous practices functioning at different levels. A common phenomenon is the sudden emergence in relatively full fledged form of a deity and its worship, for example, Ganesh, Durga and Radha and of cults and schools of thought like the Shaivite and Vaishnavite sects, the adoration of Kartavirya, Dattatreya etc. Though philosophers and Sanskrit religious authors ignored them, they were winning status among the people, and the time came when they first entered the popular books, the puranas, which provided a liasion between the learned classes and the masses.

In Manipur, too, we notice the propagators of Vaishnavism and the rulers stressed the translation and popularisation of the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas. Ancient manuscripts containing the translation of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana have been found. Public reading also played an important part in this. Srinivas (1989, p. 63) has said: ‘The fact that the institution of the harikatha, or public reading of the epics and puranas by trained masters of the art, was popular pastime and made it possible for Sanskritic Hinduism to reach even the illiterate masses.’ In Manipur, too Vaishnavism came to be propagated by means of public reading: folklores describing the vision of Sri Krishna in a dream of King Jaisimha and the taming of an elephant in Assam or the dream vision of the Rasalila, the acceptance of Vaishnavism by ancient gods and goddesses due to divine intervention etc told to people through the medium of public. Reading greatly influenced common man.

Besides these means, the various pilgrimage centres played an important part in the process of Sanskritisation as well.

Every great temple and pilgrim centre was a source of Sanskritisation and the periodic festivals or other occasions when pilgrims gathered together at the centre provided opportunities for the spread of Sanskritic ideas and beliefs. Several other institutions such as bhajan, harikatha, individuals like sanyasi and other religious mendicants also helped to spread ideas and beliefs of Sanskritic Hinduism. (ibid)

In Manipur we also see that the king himself and, through his encouragement, the subjects too would visit various pilgrim centres in order to gain virtue. The king went on a visit to Nabadwip whilst his daughter also spent the last days of her life there. The people of Manipur visited various Vaishnava pilgrimage centres like the river Ganga, Vrindavan etc. In conclusion we may critically judge the Brahmanical form of Hinduism as the main factor in the process of Sanskritisation. Hinduism is a religion which has the innate capacity of assimilating easily other streams of ideas within itself in an absolute oneness. The main philosophy of the Vedic Hindu religion was that there was one god who was omnipresent in all ages and places. He was worshipped in various ways and various forms but he remained the one and indivisible. All deities were but different forms and names of the same supreme god. The task of accepting the deities worshipped by the tribes, as a result of the Sanskritisation process would therefore gradually be assimilated into the fold of mainstream Hinduism. As Srinivas (1989, p. 60–61) says:

The idea of manifestation, which resulted in a deity or even an historic personality being made out to be a great god, was a potent source for the absorption of the deities of low castes and tribal people... Many Sanskritic deities worshipped in India today begin their existence in the dim past as the deities of low castes and tribes.

Thus the acceptance of deities of the low castes or tribes as avataras (incarnations) or devotees of Hindu gods and goddesses and getting their identification as such is possible mainly through myths or folklore. "Identification not only enables wide cultural gulfs to be spanned, but also provides a means for the eventual transformation of the name and character of the deity, and the mode of worshipping him" (Hodson, 1975, p. 5).

After the ingress of Vaisnavism in Manipur, many local gods and goddesses were identified as the avataras of Vishnu. For instance, the popular god Sanamahi gained acceptance as a devotee of Vishnu through the help of a folk tale, Pakhangba became the snake avatara of Sri Krishna and the first king of Manipur named Pakhangba has been identified as, according to the royal chronicle, the grandson of Babrubahana or the great grandson of Arjun and Chitrangada. "The legend of Arjuna and Chitrangada which is very well-known in India, became, one might say, the pivot for linking up Manipur with Brahmanical Purana tradition" (Chatterjee, 1974, p. 124).

However, it may be observed that in the areas where the Sanskritisation process was active, the rulers have on the one hand tried to spread the Brahmancial culture and on the other they have actively faced opposition from the conservative sects of society. It has been factually observed, however, that the disunited society, which is ultimately united with the mainstream of Aryan culture through the means of Sanskritisation, does not completely lose its social modes or religious rituals. Their traditional rites and culture run parallel to the Brahmanism Hinduism and social culture and there is also a mutual exchange of culture and rites. The two streams are neither completely separate nor can they be identified as one.

This is clearly seen in Manipur. The reforms heralded in Manipur by the introduction of Vaishnavism did not succeed in completely wiping out the traditional tribal culture. The effort put in to wipe it out proved futile. The forces opposing the Sanskritisation process have been always active, hence when King Garibnawaz tried to propagate this process with royal force it was strongly opposed time and again, because his intentions had been to completely annihilate the religion practiced by the Manipuri tribes and establish the Ramandi Vaishnavism.

Proof of this is found in the events where he showed disrespect to the local gods and goddesses, wanting to stop their worship altogether. In the year 1726, he buried the idols of nine Umanglais under a tree, breaking the images of Panthoibi, Sanamahi etc, confiscating the jewellery of the gods and goddess and destroying existent temples. Besides this, he burnt one hundred and twenty valuable texts. But King Bhagyachandra realised that no matter how philosophically and spiritually rich a new religion might be, the local culture would never be wiped out. He also realised that Hinduism, especially Gaudiya Vaishnavism with its humble devotion and philosophy that all gods and goddesses are but separate forms of the one almighty, and the belief in avatara (incarnation), could easily assimilate the existent folk religions and coexist peacefully without any visible opposition. Hence he had no intention of completely wiping out the local deities of rituals of worship. He established Govindaji the almighty and the traditional local gods and goddesses as his incarnations or devotees. The other procedures utilised by him in this process of Sanskritisation have already been mentioned above. Chatterjee compares this with the religious development in Japan. He writes:

Just as in Japan, Japanese Buddhism is not the pure religion of the Mahayana which came to Japan in the 7th century AD by way of China and Korea. The Japanese people still keep up their old pre–Buddhistic religion, the Shinto or ‘Way of the Gods’ and present day Japanese Buddhism is called by the name of ‘The Ryobu Shinto’ or ‘Mixed Shinto’. In this way, the Japanese from their own native culture and mentality have given something new to the Buddhism which came to them ultimately from India and Buddhism acquired in its Japanese environment a new horizon in the words of its thought and artistic self expression. The same has been the case with the Hinduism of Manipur. (in Singh, 1976 p. xii)

The indigenous religion that the people practised remained in its native form, while the Vaishnava religion acquired a new and unique look as the Meiteis absorbed it into a special dimension that became a blend of the old and the new.

Manipur Hinduism gradually became a synthesis of the old Meiteis religion with its gods and goddess and myths, its own legends and traditions, its social customs and usages and its priest and ceremonial [sic] and of Brahmanical Hinduism with its special worship of Radha and Krishna. Meiteis never gave up their culture and tradition. (Shyam, 2006)

However, the main instrument utilised by king Bhágyacandra in spreading Vaishnavism was dance. The Manipuri society is completely enamored of dance. As the ruling class enforced Caitanite Vaishnavism, the worship of the Vaishnava Gods (such as Rádhá and Krishna) was introduced and a year-long program of Vaishnava worship was set up. This Vaishnava religion played the pivotal role in the development of the classical dance tradition in Manipur. In each and every festival observed by them, dance is a must. Folk tales say that Shiva and Parvati danced the Rasalila in a valley surrounded by mountains while the serpent king lit it up with the dazzle of his crown jewels or ‘mani,' which is how ‘Manipur’ got its name.

We also learn that the seven gods and nine goddesses danced to create the world; a dance now referred to as Manipur’s primeval dance. Therefore during the laiharaoba festival the Maibis please the Gods through the medium of dance. Also during the festival the love story of the Khamba Thoibi is enacted in the courtyard of a temple. Everyone is permitted to join in the event. In Rasalila all the ladies in the community can participate in the dance as 'gopinis' 4 . In this context it may be mentioned that the ladies participated as gopinis portraying characters based on 'madhura rasa' 5 or Vaishnava philosophy sentiment. The Khamba Thoibi is portrayed through dance and later Khamba-Thoibi was regarded as the avatara or incarnations of Shiva and Parvati, the Hindu gods.

Worship of the deities Krishna and Radha through dance. Photo courtesy Dr Thoiba Singh.

Worship of the deities Krishna and Radha through dance. Photo courtesy Dr Thoiba Singh.This is clearly seen in Manipur. The reforms heralded in Manipur by the introduction of Vaishnavism did not succeed in completely wiping out the traditional tribal culture. The effort put in to wipe it out proved futile. The forces opposing the Sanskritisation process have been always active, hence when King Garibnawaz tried to propagate this process with royal force it was strongly opposed time and again, because his intentions had been to completely annihilate the religion practiced by the Manipuri tribes and establish the Ramandi Vaishnavism.

Proof of this is found in the events where he showed disrespect to the local gods and goddesses, wanting to stop their worship altogether. In the year 1726, he buried the idols of nine Umanglais under a tree, breaking the images of Panthoibi, Sanamahi etc, confiscating the jewellery of the gods and goddess and destroying existent temples. Besides this, he burnt one hundred and twenty valuable texts. But King Bhagyachandra realised that no matter how philosophically and spiritually rich a new religion might be, the local culture would never be wiped out. He also realised that Hinduism, especially Gaudiya Vaishnavism with its humble devotion and philosophy that all gods and goddesses are but separate forms of the one almighty, and the belief in avatara (incarnation), could easily assimilate the existent folk religions and coexist peacefully without any visible opposition.

Hence he had no intention of completely wiping out the local deities of rituals of worship. He established Govindaji the almighty and the traditional local gods and goddesses as his incarnations or devotees. The other procedures utilised by him in this process of Sanskritisation have already been mentioned above. Chatterjee compares this with the religious development in Japan. He writes:

Just as in Japan, Japanese Buddhism is not the pure religion of the Mahayana which came to Japan in the 7th century AD by way of China and Korea. The Japanese people still keep up their old pre–Buddhistic religion, the Shinto or ‘Way of the Gods’ and present day Japanese Buddhism is called by the name of ‘The Ryobu Shinto’ or ‘Mixed Shinto’. In this way, the Japanese from their own native culture and mentality have given something new to the Buddhism which came to them ultimately from India and Buddhism acquired in its Japanese environment a new horizon in the words of its thought and artistic self expression. The same has been the case with the Hinduism of Manipur. (in Singh, 1976 p. xii)

The dances of the community, especially those from the láiháraobá were taken and changed according to the needs of Vaishnava sentiment. So a unique form of dance evolved, which had within it the indigenous dance elements of Manipur. But the form took a new look when influenced by the religious doctrine. Two distinct types of devotional dance came into existence—the Natasamkirtana and the Rásalilá.

The Natasamkirtana, which is a community prayer to invoke God, is primarily a male dominated ritualistic endeavor. It has many branches like the Bangadeshpálá, Natapálá, Manoharasáipálá, and Dhrumel. One branch has flowered into a female community prayer called the Nupipálá. The Manipuri Rásalilá embodies the facets of nátya, that is, the ancient drama practice of India. But positive enriched features suggest a distinct evolution in technique and presentation. The tándava or the male form and lásya or the female form of dances is markedly brought into being here. The Rásalilá is structured according to the need of the Vaishnava religion practices. The Samkirtana is the prologue to the Rásalilá. The men carry the pum, the kartála, manjirá and dance in cholom style. There is a knee bent and a slight front bent of the torso that gives the characteristic of the body position of the cholom style. The essence of the dance is to play the instruments like kartála, pum, manjirá and dance.

Manipuri classical dance stands out markedly in the multiplicity of Indian classical dances for its special features derived from the inter mixing of the diverse people of the area. The other classical dances of India, which travelled from temple to stage, experienced modifications with the shift of the arena. Gradually the temple premise, that is, the place of origin, lost its importance. The current stage presentations are the only identity those dance forms have.

But in Manipur the classical dance is still presented as a temple performance and follows all the detailed rituals as at its origin. The reason behind the continuity to date of this tradition is the participation of the community. Dance was never extracted from the social festivity or ritualistic practices and developed for individual performance. The duty of the principal dancer is to lead a group of dancers to the place of performance and guide the ritual with their involvement in them. This is evident in both Láiharáobá and Rásalilá.

In láiharáobá the máibis lead the group while in Rásalila the makokchingbi guides the rest of the female artists enacting the gopis/sakhis i.e. the female participants as friends and devotee of the deities Radha and Krishna. The ceremony of rituals is always around the deity and in the public temple domain. For láiharáobá the areas in front of the village temples are used for celebration. Since the whole neighborhood joins in, the room of the deities becomes insufficient to accommodate the large number of people. So the deities, láibou and láiningthou, are brought out of the temple and placed in the open ground. The máibis face the shrine and dance the láicing jagoi. It is also believed that god becomes a part of this celebration and thus láiharáobá or the merrymaking of gods persists.

The same procedure is followed in case of the Rásalilá too. The deities Krishna and Rádhá are brought out of their rooms of the temple and placed in the centre of the Rásamandali. The participants go round facing them singing and dancing. In Gosthalilá the deities are taken out to the meadows and dances are performed on the ground. Interestingly, the máibis’ dance genre is reflected in the dances of Bhangi Pareng in Rasalila. The Khuntum 6 and Khutsá 7 jagoi 8 , the khujengleibi 9 hand movement are used repeatedly in Bhangi parengs.

The age-old symbol of ‘the snake biting its own tail’ called the Pákhángbá is manifested in all movements. Thus the curve of the number eight has become the foundation of the technique of the dance form. The máibis in láiharáobá move making complex patterns arising of the figure eight called the lairen mathek on the ground, the pungoibás in Natasamkirtana move with the pung making the interweaving movement of eight on the ground of the mandap, and the gopinis in Rásalila show signs of eight in the torso, hand and feet movements.

We see from the very beginning the people of Manipur accepted dance as an inseparable part of their lives. Hence during the popularisation of Vaishnavism by King Bhágyacandra, the dancing of the Rasalila of Radha—Krishna was also made popular. The main feature of this dance is that it has a totally religious function and is deemed to be very holy. There is no intention of performing it for amusement. It is usually organised in the courtyard of the temple of Govindaji as also in the temple courtyards of various localities. Raja Bhágyacandra's endeavor was to make it respectfully acceptable by the populace. Hence, dances were planned only on the devotional composition texts like Srimadbhagavata, Geeta Govinda etc. These Rásas were performed on a particular day in a sacred spot. Dances were also directed in a way so that the devotional aspect could be made prominent. ‘The Meiteis are now staunch Hindus, and through them Manipur has been made the easternmost outpost of Hindu culture in India. In modern times the Manipur Vaishnava dance—the Rása—has made a great contribution to the art of the dance as an expression of modern Indian culture’ (Chatterjee, 1974, p. 48).

In Manipur no separate classes of 'dancing women’ were created along the lines of dasiattam of the south India. In order to enhance the significance of the Rása dance, the king allowed his daughter Bimbavati Manjari to participate in the role of Radha. The costumes of the Rasa dance too were designed to enhance its devotional aspect. The dancer’s face is completely hidden behind a veil, the protruding poloi and poshwan (skirts) 10 covered a woman's body very well while the glinting of the embroidered work on the outfits serves to bring out an ethereal effect. The whole thing has been planned in such a manner so as to bring out only the emotion of devotion in the viewers.

The king also popularised myths centering on the Rása dance, for instance the divine decree to establish the idol of Sri Krishna, the dream vision for having the Rása dance. These could encourage the people to devotedly accept the Rása dance, the theory of Rádhá and Krishna and also to acknowledge the king and his family as devotees of Krishna. The descendants of King Bhágyacandra also continued this tradition unchanged. As a result there was a steady development in the procedure of this Rása dance—in songs, instruments, dramatisation, displaying of the emotional aspects etc. And it gradually succeeded in gaining the position of a complete classical Indian dance form, known as Manipuri.

On a closer look into the process discussed above, one finds uniqueness. While adopting the Hindu frame of living, as an effect of Sanskritisation, the Meiteis never dissociated from their innate indigenous sensibilities. So we find Hinduism taking a ‘Meitei-turn’ in Manipur. Where in India did the Samkirtana evolve as the abode of the refined tála-system, a methodical presentation of body language, a sophisticated percussion play, and an intricate ritual structure? Where in India did the Rásalila find such a heavenly environment with amazing costumes, sinuous movements, spectacular singing, and atypical conch playing? It was with the Meiteis, who with their artistic consciousness created their own presentation stamped with their individual awareness of art and culture. They in turn contributed a different flower on the branch of Hinduism, completely contrary to what is prevalent in the rest of India.