As one of Australia’s leading contemporary dance ensembles, South Australian-based Leigh Warren & Dancers has graced stages across the world—often performing to sell-out crowds with their innovative and award-winning productions. However, it’s in the realm of community dance—through an intimate series of performances for patients receiving treatment at a hospital in their hometown of Adelaide—that the company has been most deeply rewarded.

The notion of taking dance outside its traditional stage setting and into the very heart of a community has always appealed to Leigh Warren—artistic director at Leigh Warren & Dancers, one of Australia’s most respected contemporary dance companies. Throughout its 18 year history the company has engaged in numerous community dance projects—but none has had quite the impact on both the audience and the dancers themselves as Medico Manoeuvres—a series of specially choreographed dance pieces for ward patients at an Adelaide hospital.

Designed as diversional therapy, the performances were presented at Flinders Medical Centre (FMC) in 2007 and 2009 through its Arts in Health programme that integrates art and cultural activities into the life of the centre for the benefit of patients, visitors and staff. It’s the largest and most diverse program of its kind in Australia.

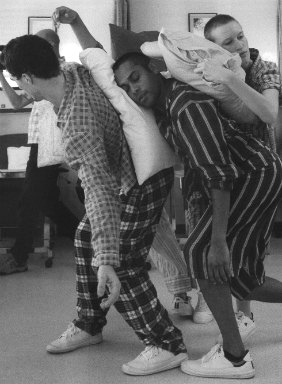

Medical Manoeuvres by Leigh Warren & Dancers at Flinders Medical Centre. From L – R: Adam Synott, Deon Hastie and Gala Moody. Photo: Alex Makeyev

Medical Manoeuvres by Leigh Warren & Dancers at Flinders Medical Centre. From L – R: Adam Synott, Deon Hastie and Gala Moody. Photo: Alex MakeyevLeigh was introduced to the concept of diversional therapy in 2006 by Adelaide neuroscientist, Professor Ian Gibbins, who approached him to work on the community programme, Science Outside the Square.

“Our presentation was about the connection between the mind and body movement and how synaptic pathways in the brain change when you dance or witness movement,” says Leigh. “From that project I discovered how movement and music, when combined in dance, can create a diversion from self consciousness, which has the ability to change mood and behaviour generating a sense of wellbeing.”

An invitation followed for Leigh to undertake a residency at the FMC and design a series of performances for patients in wards ranging from oncology and paediatrics, to renal dialysis and the mental health unit.

“The aim of diversional therapy is to distract the patient with a welcome and non-confrontational surprise,” says Leigh. “In that moment of distraction and engagement, they stop thinking about their condition and their body experiences enormous relief. Later, when they recall the moment, it brings further relief and benefit.”

In designing the individual dance pieces, Leigh worked closely with the clinical nurse consultants on the relevant wards to determine music selection and how best to utilise the different settings without compromising patient care or comfort.

“These performances had to result in a win-win situation for the patients and the dancers, so consulting with those nurses was a crucial part of the design process,” says Leigh. “It informed every element—the choreography, the music and the costumes.”

For the paediatric ward, dancers donned pyjamas and entered the space unannounced with pillows under their arms—before performing to an upbeat soundtrack.

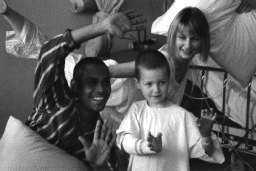

Medico Manoeurvres by Leigh Warren & Dancers at Flinders Medical Centre. From L – R: Deon Hastie, patien and, Lisa Griffiths. Photo: Alex Makeyev

Medico Manoeurvres by Leigh Warren & Dancers at Flinders Medical Centre. From L – R: Deon Hastie, patien and, Lisa Griffiths. Photo: Alex Makeyev “At the start, the kids had no idea what was going on—some thought the dancers were just new patients arriving,” says Leigh. “The pillows were integrated playfully into the performance and many of the kids joined in. In the end, pillows were flying everywhere. It was extremely uplifting and importantly, had the desired effect of creating a welcome surprise and a gentle distraction for the children.”

The oncology ward called for a subtler approach. While pillows and pyjamas were again incorporated, the use of the beautiful Alina by composer, Arvo Pärt evoked a more tranquil atmosphere.

“This piece was very delicate and tender, with the dancers softly cradling the pillows in their arms,” says Leigh. “It was remarkable to watch the reaction of the patients who weren’t quite sure if they were hallucinating because the routine had started so organically. Watching, you could almost see the patients leaving their bodies and travelling across the room – just giving themselves up to

the performance.”

One of the most moving moments for Leigh and the dancers took place in a general ward, where a woman lay close to death, her daughter by her side.

“The mother was falling in and out of a coma and we weren’t sure whether to go ahead,” says Leigh. “But her daughter felt she would love the feeling of such gentle movement taking place around her. As the dancers performed, the daughter would describe what was happening to her mother. The woman would wake for a moment and engage in the process and then lapse back. The daughter was elated her mother had been able to experience such a beautiful vision of tenderness and connection and they’d been able to share that moment together.”

Another morning performance for psychiatric patients resulted in an incident free afternoon.

“For this piece the dancers dressed in nurse’s uniforms and performed to tango music,” says Leigh. “The pleasure and amusement the patients experienced in those first few moments of the dancers coming in, when they thought perhaps the nurses had gone a little loco, just seemed to bring about a really peaceful afternoon, which was great for patients and staff.”

The residency was an equally rewarding experience for Leigh and the dancers.

“It certainly helped me as a choreographer,” says Leigh. “It’s an awareness thing. Working away from the stage in the community, especially in a medical arena, requires you to be very aware of response. It’s crucial in the design phase to be able to ‘read’ people and understand the different situations in which you’ll be delivering the work and how it might be interpreted.”

For the dancers, the challenges came at a practical and emotional level. The wards were far removed from the comparative safety of a theatrical stage: props replaced by life-supporting medical equipment, surgeons and nursing staff instead of production and lighting crew and an audience which could not only be seen, but was held captive in their hospital beds.

“Over time, they began to read the emotional state of a particular space extremely well and learnt to control their reaction to that instead of being washed over by it,” says Leigh. “I think an experience like that can only give a dancer more confidence to perform in a whole range of settings.”

The project resonated particularly for dancer Chris Hewitt, who performed in 2009.

“Initially, Chris was quite anxious about the performances,” says Leigh. “He’s a very caring, sensitive person and, like many people, wasn’t comfortable in hospital environments. As it turned out, he found the experience so rewarding he’s now making connections with other medical centres around Australia which have similar arts programmes and hopes to get a pilot programme up in Victoria.”

Leigh has also been approached by another South Australian hospital to design similar performances for their women’s and children’s unit. While keen to pursue the request, he admits he has much to learn about diversional therapy and would like to see the formation of a group of medical and artistic professionals, to look at the area full-time.

“There’s so much more I want to understand about this subject, but I believe the potential benefits are huge,” says Leigh. “For me, it’s important to see dance having a deeper relevance for people – a life and purpose beyond the stage setting. I love the mystery of the theatre and the emotions you can provoke through a traditional stage production but it’s also important to have the breadth to reach out and do other things – and what could be more rewarding than to bring even the briefest relief to another human being through the experience of dance?”