I need to preface this presentation by confessing that this is, strictly speaking, not a research paper but a commentary on the current state of play within the dance world (and I refer primarily to dance as art in that respect), though I will refer to research by others as well as drawing upon my own research interests in the area of arts and cultural policy. It could well end up sounding like a polemic followed by a call to arms.

I come wearing my full complement of hats—dancer, dance educator, dance maker, dance critic, and academic. This last hat includes my current position as lecturer in the postgraduate program in Arts in the School of Creative Arts at the University of Melbourne where I lecture in Arts and Cultural Policy. I should state up front that this presentation relates specifically to the Australian dance field, which is generally felt to be in fairly dire straits. However, I am sure that much of what I say will be familiar to our international visitors. This presentation has been titled “Re-defining the Field—Expanding the Field.” In fact I want to knock down the fences of the field to create a borderless place somewhat akin to Suzanne Kozel’s illustration in her keynote address of the cellular construction of our bodies’ connective tissues within which networks can emerge, evolve and adapt to changing circumstances and needs. We are in a stage of transformation and transition and need to be open to diverse alternatives in terms of both practice and policy.

Having said that I want to knock down the fences I nevertheless find myself using the term “field” quite frequently as a way of defining the various elements that contribute to dance’s social and industry functionality. As my friend and colleague Shirley McKechnie often reiterates we are a structure-seeking species. Society demands organisational structures. Pierre Bourdieu’s notions of field, players, habitus (the rules of the game) and capital offer a useful and flexible model that escapes the rigidity of some anthropological models. Bourdieu recognises our capacity to adapt, while maintaining a degree of acceptability because of our understanding of the structures and conventions that rule the field of play. We know how to vary our conduct according to the position we might occupy in the field, and we read others according to their position in the field.

So in this presentation I am looking particularly at three aspects of the dance field: the education and training system, the structure of what the politicians like to refer to as ‘the arts industry” and the policy system that to a very large degree benignly regulates art form practice through our reliance on its beneficence. These are the fields that tend to dominate and shape our behavioural patterns and expectations, capturing and limiting our perceptions or beliefs of what is and is not possible. We need to move beyond these boundaries.

So far in this conference there have been two frequently recurring themes: sustainability and ecology. My focus on sustainability varies slightly from Kim Vincs. She referred mostly to the possibility of individuals making a sustainable living within dance. My concern is for the sustainability of the art form itself, its need of nourishment that supports development and innovation. Of course that cannot happen unless artists are able to dedicate sufficient time to the practice of their art and craft. We do not tolerate casual practice in our doctors, our accountants or our corporate CEOs because we know that implies less than the optimum performance. It is just as imperative for artists to engage intensively in their art form if their art is to fulfil its function in society—to speak with a clear and compelling voice, to reflect and create an awareness of the cultural milieu that shapes us as social beings. Lack of opportunity to do this has implications for the nation’s cultural health.

Ecology—the 'e' word has been around a long time—it refers to an interdependent system. If one element suffers then the system will need to adapt, and depending on the areas of weakness, the system could collapse resulting in extinction. In this respect I see the dance field as a food chain—with each element feeding off the one below. Each element has an essential role to play in supporting the total system.

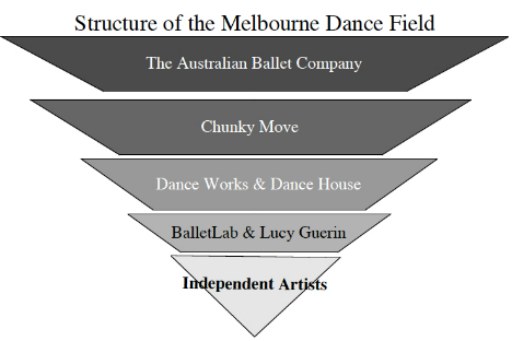

This illustration is a simple schema of the Melbourne dance performance scene—it would be matched by a similar structure for most of our other capital cities

This illustration is a simple schema of the Melbourne dance performance scene—it would be matched by a similar structure for most of our other capital citiesRather than drawing it as the typical pyramid structure I have inverted the structure because that best reflects the relative levels of resourcing, power and public profile for each sector. At the top we have the Australian Ballet—our national flagship, which by comparison to all other sectors seems incredibly well resourced—of course it needs to be, with a substantial ensemble of dancers and all the ancillary supports that are needed to keep it running. It is enormously hardworking, giving more performances in larger venues than any other company in the country, consequently reaching a far larger audience. In the eyes of most of the potential dance audience, this is DANCE! Because of its substantial dependence on box office to sustain the organisation, this leaves it with limited time for creative development. While it does commission new work the time constraints and fragmented access to dancers places significant limits on the choreographers’ opportunities to experiment.

Next in the scheme is our state funded contemporary dance company Chunky Move—with its purpose-built studio. Chunky Move has thought quite strategically about how to function—it does not maintain an ensemble but contracts dancers as needed, although it has now built up a fairly consistent pool of performers on which to draw. It has done this for two reasons—firstly to allow for maximum creative flexibility to undertake very diverse projects; secondly to avoid the financial strain of maintaining an ensemble. It does however have the advantage of a permanent home and management structure, which it also offers as a resource for a limited number of independent and emerging artists. Chunky Move is an example of a company striving to adapt to current conditions. They have been proactive in presenting work in different milieu and in different formats, in finding ways to engage audiences and using their relatively stable position to provide leverage for selected independent artists.

Thirdly we have two other funded organisations—Danceworks—a company with a long history of encouraging choreographers—but which is now reduced to an almost anorexic state—presenting only occasionally and for short seasons, and Dancehouse—an organisation established to provide a space for independent artists to rehearse, make work, do classes and present performances. It produces a limited number of curated seasons. Additionally, independent artists can self-present in either of its two performing spaces. It has become an important hub for exchange of ideas and development of new work, but is also struggling to sustain itself. The audiences for both these organisations will typically be generated from within their own domain—people with a vested interest in new and experimental work.

Underneath all of this is the independent sector—the group with the most creative flexibility, but with the least resources, limited to working in a piecemeal fashion. While there are a number of mature choreographers of stature, a great deal of activity is fuelled by young dancers entering the profession. In today’s world they have significantly diminished opportunities to move through the traditional rout—becoming part perhaps of a small ensemble, learning what it means to be an artist, observing the making and staging of work. Such small ensembles were once fertile ground for developing choreographers; giving them the chance to try their wings, get their work seen, receive feedback.

However, in the early nineties many of these companies were reduced to intermittent project funding resulting in loss of continuity, loss of work for dancers, loss of infrastructure and loss of a consistent audience profile. This has had negative outcomes both for artists and for audience development. As a result of this erosion of the small company network, the vast majority of graduates become, perforce, independent artists. If they are going to dance, then they have to go it alone—gathering a bunch of friends, hopefully getting a grant, usually totally inadequate, and within the timelines of the grant-making procedure, producing a work which usually will have a brief showing to a small audience, mostly of the already converted. Under those conditions much work is undercooked and malnourished. Limited showings mean limited feedback. Limited audiences, with a vested interest, means ideas are not tested or challenged. The work is in danger of being self-serving, and self-replicating—with a decreased palette of aesthetic interests and possibilities. The whole thing becomes self-defeating, leading to the oft asserted, but I believe incorrect view, that there is a diminishing audience for contemporary dance.

I must hasten to add that there is some truly exquisite work coming from mature artists who choose to work in the independent sector. Yet even their work has such a limited reach that it can contribute little to expanding the experience of a wider, less dance-literate audience who might well be moved to embrace a broader spectrum of dance performances if they could be introduced to some of this work.

A 2002 report for the Cultural Ministers’ Council 1 —the small to medium performing arts sector states:

The Working Party found overwhelming evidence that the Small to Medium Performing Arts Sector is essential to the artistic vitality and the ongoing development of Australia’s performing arts. It is the main source of new Australian works in the subsidised performing arts. The Sector provides access to the arts, offers many employment opportunities and in particular gives young and regionally based Australians opportunities to participate (5)

The research did not include the independent sector, which is growing significantly largely because the small to medium sector is diminishing. This means that it is the independent artists who must try to fill the gap – create the diversity, bring in the innovation, and presumably build audiences. They go willingly, with an enthusiasm for their art, and a missionary belief in its worth, but are ill equipped to deal with the environment they enter—the policy system is failing them—the lower end of the food chain is suffering from chronic malnutrition, putting the ecology in danger of collapse. Yet, as the previous diagram suggests, the whole art form is balanced perilously on the tiny shoulders of this creatively lively, but chronically malnourished independent sector—a growth area starved of sustenance.

In her research into the choreographic process Professor McKechnie identified it as a dynamical system—an exquisite microcosm of social adaptation negotiated between choreographer and dancers. A fundamental element of this process is the time to devise, adapt and finally commit—it is a complex decision-making process. In writing about the decision-making process, Townsend and Busemeyer referred to William James’ The Principles of Psychology published in 1890. What he describes beautifully captures the experience of art making.

The deliberation may last for weeks or months, occupying at intervals the mind. The motives which yesterday seemed full of urgency and blood and life to-day feel strangely weak and pale and dead…. something tells us that all this is provisional, that the weakened reasons will wax strong again, and the stronger weaken…and that we must wait awhile, patient or impatiently, until our mind is made up for good and all (1995 in van Gelder & Port p102).

The key element in this description is time. Artistic processes need time for ideas to germinate, break through the soil, blossom and bear fruit. The policy process however is driven by the desire for deterministic outcomes achieved within tight timelines. Productivity is the order of the day—but of what value will that so-called productivity be if it is undernourished, and the creative potential unfulfilled? The policy system that supports the arts, allows no room for prevarication or vacillation. It exists as a pattern of application deadlines, application guidelines, assessment criteria and acquittals, all couched in terms that line up with government policy agendas.

In cultural policy this impacts, in various capacities, upon the individual artists involved in the system—the amount of time and resources that they have to create work, the terms under which they are eligible, and, in consequence, the ways they are influenced to express their ideas. These artists are not just reacting to social trends, but to the limiting conditions of policy imperatives. The real values to society of the art experience disappear under the weight of statistics: resources outlaid, number of artworks completed, box office statistics and hypothesised economic spin-offs.

Yet we turn to this system because we cannot see alternatives—cannot find our way out of the policy field. Even the peer system itself, which we have prized so highly, can no longer cope with tasks demanded of it. Peers have an important role to play in terms of understanding the processes, recognising the trends, acknowledging and arguing for investment in artistic merit. However, peers cannot create resources – they can only identify the need. In that sense they are powerless, caught in an impossible vice between the frustrations of artists who fail to attract support and a government that appears deaf to their recommendations. As presently practised the peer assessment system is a strategy pointed towards redundancy.

We have become so inculcated into the habitus of this system, that we fail to recognise our adaptation is the result of a subconscious conformity to ritualised practices. The habitus, Pierre Bourdieu suggests, “ensures the active presence of past experiences, which, deposited in each organism in the form of schemes of perception, thought and action, tend to guarantee the ‘correctness’ of practices and their constancy over time” (1990, 54). Our capacity to find ways of working outside the system and to claim appropriate working conditions for adequate creative development, is undermined by our reliance on the policy system and an inability to imagine alternatives. We need to break down the fences, not shift the fence posts.

One of the strongest trends in policy since the mid-nineties has been the push for audience development. The second major research project led by Shirley McKechnie dovetails nicely with this obsession. Conceiving Connections goes beyond the market driven research that looks at demographics, education and income levels of arts consumers. It seeks to identify how audiences glean meaning from observing contemporary dance. What cues assist audiences? How might the knowledge gained influence choreographers? More contentiously, we also should be asking what is the relationship between choreographers and their audiences? It is a relationship often overlooked.

There is no doubt that contemporary dance demands a lot of an audience. The diversity of approaches to performance, to movement language and to content renders much work opaque to all but the initiated. Often it seems that the choreographer is happy to reach a small and exclusive audience. Program notes may prove totally mystifying, or be non-existent. The performance style may be inwardly focussed, offering little for the audience to relate to either in terms of symbolic representation or human communication. The movement material may be dense, a relentless stream of multi-directional action, so hyperactive that there is no time for contemplation and little hope of retaining movement patterns in the memory. Too often there seems to be a self-serving conviction that the desire to perform is justification enough. Audiences should be content to passively accept whatever is offered.

Choreographers, and dancers, are in love with movement. Choreographer Glen Tetley refers to dance as ‘heightened life’, a desirable end in itself for the maker and the doer. But what of the watcher? The training of the dancer does not prepare them to consider this issue. The perfection of movement is the only goal. There is little in our social conditioning or education that recognises the influence of movement language, even though we engage in reading it unconsciously. The dancer and choreographer, so strongly immersed in the medium, assume or ascribe an expressiveness that is not necessarily evident to the lay audience. The result can be a significant gap between the belief of the dance artist and the expectations of an audience.

So what might be some strategies to help resource graduates to connect with the world they will enter, or which will help them to bypass systems that are failing them in their pursuit of a career in the arts? Firstly let’s consider the training institutions: given the constraints within which they all struggle to fulfil their mission are there simple strategies to assist their students to find a place for their work in the wider community?

- Why not have students attend several performances of work that is challenging and unfamiliar (it does not have to be, possibly should not be dance). Have them write a review, not of the performance, but of the experience of attending that performance and of their struggles to find a point of connection, and insight into its intent.

- Why not have a fieldwork unit that requires them to get to know their local government, how it works, who the key players are, what recognition of and support for cultural activities exists. An absolute requisite of this project would be to attend a council meeting and get to know the local councillors. Then devise a hypothetical project that taps into that community.

- Alternatively, why not ask them to find a form of dance—social, ethnic, religious, therapeutic with which they are unfamiliar. Meet with the people who participate in it—join in, get an understanding of what they value in it, then write a report which compares and contrasts that dance experience with their own. What are the similarities and differences? How might that serve as an opportunity for new work and new relationships—a sharing rather than an appropriation?

All of the above strategies place the students in a wider referential framework beyond the sheltered confines of their dance education. They provide opportunities to build community, political and social connections—all essential elements in any professional career.

Within the policy system we need to grasp the opportunities foreshadowed by social trends. Why not think how dance making at the entry level of the spectrum might leverage the current trend for younger generations towards a greater interest in a diverse cultural life, and their tendency towards what the futurists describe as a sort of tribal social grouping. How might this be conscripted as a fluid community base of networks and relationships of support and consumption?

How might the peer system itself become not a labour, not a reaction to the appalling constraints but an exciting visionary and proactive adventure? What reconception of the peer process might allow their role to expand beyond struggling with impossibly limited budgets that have no hope of addressing the impossible levels of demand?

Granted the problems here lie not within the funding bodies themselves but with the governments whose political will is at best limited, and relates largely to what the arts can do to sell Australia, the state, the municipality—arts as a marketing tool. Political will at the highest level is the only way we can significantly change the present policy situation. Let us hope the newly formed Council for Humanities, Arts and Social Services can make headway on this. How might we become more proactive—supplementing the hardworking efforts of our principal advocacy body, Ausdance.

I would like to end on a more positive note, with my final wrap in The Age for last year’s Melbourne International Festival of the Arts.

I wrote:

This year’s Melbourne International Arts Festival has offered a feast of body-based performance, providing us with pretty much the full spectrum of dance’s role in human society. We have seen dance and physical theatre as spectacle –and as anti-spectacle, as violent virtuosity, as youthful or avant-garde protest and as gentle and not so gentle comedy.

Dance as recreation has been an absolute star in the Dancing in the Streets program in Federation Square and around the state as part of the Bal Moderne events. Dance as courtship has featured prominently in the Australian Tango Festival, while dance as religious ritual and mystic experience featured in The Whirling Dervishes, Michelle Mahrer’s recently released film—Dances of Ecstasy and Incompatibility by Tony Yap and Yumi Umiumare.

Just to prove that dance is up there with the latest trends, technology has featured prominently in Lucy Guerin’s Plasticine Park, the Body on Screen program at ACMI, and Inside 03 – The Technology Project (2003).

The point is that this festival recognised and celebrated the diversity of functions that dance serves in society—providing an opening for dance lovers of all varieties to engage with the festival and an opportunity for those less well versed to sample a spectrum of dance covering performance, recreation and ritual. There was work that was intellectually challenging, shocking, entertaining and amusing, as well as the chance to dance.

I fear that, too often we forget there is a whole universe of dance forms and functions that are part of the total dance ecology. These have social appeal and meaning beyond our often highly individualistic choreographic pursuits. Melbourne Festival worked so well because its comprehensive programming acknowledged that spectrum, and left audiences begging for more. It was an absolutely joyous festival – one of the best dance festivals I have ever attended, not because all the work was fabulous, but because it was a true community celebration.

So – from all of this what do I want for the dance of the very near future?

- I want to see structures that no longer work for our art form and its ecology discarded.

- I want to see young dancers being brave and going out into their communities leveraging support, becoming known and valued for what they can contribution, standing for local government, making their voices heard and their actions seen.

- If the policy system no longer works for you then bypass it. Grow your own visions and find the right partners rather than writing yet another grant application. But do it with a sense of respect for those you hope will view your work and for all the wonderful dance that has gone before.

- I want the dance world to reclaim some autonomy—to force the systems to follow, but I want it to do so with a more expansive vision of what dance is, and what functions it serves.

I have long admired the work of William Robinson, one of Australia’s most eminent landscape painters. What is interesting about his work is the way he plays with perspective – presenting a multiplicity of view points so that when observing it one feels projected into a kind of free floating state with multiple choices about how to engage, where to look, what connections to make. That is what we need to embrace at the moment. So let the revolution begin!

References

- 2004, Resourcing dance: A review of the subsidised dance sector, the Australia Council, Sydney.

- Ausdance. 2004 Media Release 1 April 2004.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996, The rules of art: structure and genesis of the literary field, translated by Susan Emanuel, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Crampton, Hilary. 2003, “Dance and physical theatre as spectacle, protest and comedy” in The Age, Melbourne, 27 October 2003, A3 p6.

- Van Gelder, Timothy and Robert F. Port. 1995, ‘It’s time’ in Van Gelder, Timothy and Robert F. Port (eds), Mind as Motion: Exploration in the Dynamics of Cognition, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts pp 1 – 43.