Josef Brown is a dancer and choreographer with Sydney Dance Company. As part of an Australia Council for the Arts Skills and Development Grant, Brown travelled to Palestine in December 2003 to learn from the work of Nicholas Rowe, as outlined in his arts workers’ manual, Art During Siege.

Rowe developed Art, During Siege in conjunction with the Popular Arts Centre of Ramallah over a four year period. It grew out of hundreds of contact hours with the children of the Palestinian refugee camps that dot the landscape of the Palestinian Territories, the West Bank and Gaza strip.

The course is designed to empower traumatised communities through using the arts as a medium to explore such life-tools as co-operation, communication, creativity and continuity. Soon upon arriving in Palestine I began grappling head-on with the fact that the ‘West Bank’, the ‘Occupied Territories’, are full of stories of tragedy and catastrophe.

Every soul met has a sad story to tell about life under Israeli occupation. Such stories are rarely ever told in the abstract but come accompanied with identifying marks and scars pointed out over and over again while travelling the beautiful yet barricaded, partitioned and walled landscape of Palestine. Here is the place where a brother was shot dead; there was once the home of a Palestinian family now torn down; here was once a village; there once a flourishing Palestinian olive grove now razed to the barren ground.

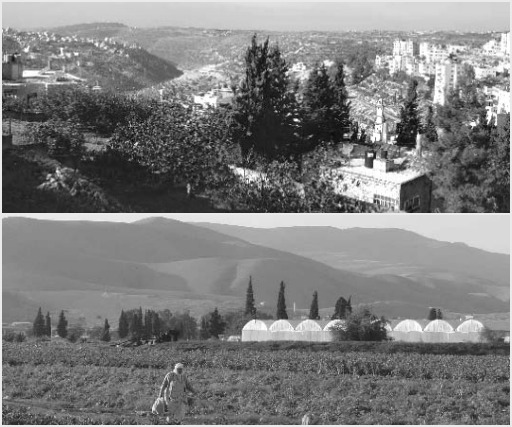

Palestinian landscapes. Photos: Josef Brown

Palestinian landscapes. Photos: Josef BrownAnd the list goes on and on. Time and time again I heard, while following the line of a pointing finger remarks such as: "Do you see there, on that mountain? That is yet another illegal Israeli settlement".

Founding member of Ramallah Dance Theatre, Maysoun Rafeedie, told me that the art of Palestine cannot be separated from the political context of this occupation. Nicholas, husband of Maysoun and also a founding member of the group, further said that art is not merely the expression of ideas, it is a place to have ideas.

So, as I sit here to write about my experiences, artistic and otherwise, of being in Palestine, I realise that this page too is a place to have ideas about these experiences and that I cannot separate them from their context, the short experience of living within an occupied Palestine.

It would be the most obvious and easy thing then to write about the tragedies of the Palestinian people, retelling the stories of all that they have suffered since Al Nakbe—the catastrophe of 1948. Instead, however, I’m going to tell a different story, one of adventure, of unflagging spirit and of love.

For five weeks I was welcomed into the Ramallah home of Nicholas and Maysoun. This is a little of their story, and the story of a small but determined group of friends and colleagues who created the first contemporary dance ensemble in Palestine, and who thus embarked on a bold adventure and a new dawn for the arts of the region.

Four years ago Maysoun, Nicholas and a handful of committed dancers from El Funoun and Siriat folk dance ensembles gathered together and began discussing the idea of creating a new entity for the Palestinian arts community. With the support of numerous organisations, both local and non-local, they were soon able to begin forging ideas into choreographic invention.

And thus in the Al Kasaba theatre in January 2004, after working in the studios of the Popular Arts Centre for four dedicated years, their work culminated in the first show by Ramallah Dance Theatre, Access Denied.

The artists of Ramallah Dance Theatre, like the folk ensemble companies of Palestine, are semi-professionals. On a regular basis they give freely of their time, usually after putting in a full day’s work at a ‘normal’ job, to come and create a production that is then performed to a paying audience.

For the folk ensembles this is often because they wish to sustain the traditional culture of Palestine as much has been leached away during years of occupation. This was sadly evident amongst the ‘Israeli Palestinians’ that I witnessed in regions such as Nazareth, who had little or no contact with their traditional Dabke dance forms.

For those who have gathered to form Ramallah Dance Theatre, the drive seems to be manifold: they want to tell new and different stories, different from those told in other mediums. They want to express in a different medium the slogans, politics and stories reiterated on television, radio and in the streets, and to express a wider range of ideas and emotions than are often accepted within the traditional Dabke form.

Some Palestinian faces. Photos: Josef Brown

Some Palestinian faces. Photos: Josef BrownThey are committed to seeing the stereotypes of Palestine, the Palestinian/Israeli conflict and the Palestinian people dismantled cliché by cliché. Importantly, I understood that their immediate aims are not directed towards performing for an international arts community but for their local population. They are creating Ramallah Dance Theatre for Palestinians. It is an attempt to make the dance medium relevant to contemporary Palestinians, and to offer Palestinians a chance to have the kind of ideas and revelations that might only come through the experience of watching movement.

It is not an easy road. Ramallah like most Palestinian towns is prone to curfews, a collective punishment inflicted on the entire populace of a town. These curfews cause the flow of normal daily activity to slow to a trickle.

Further, checkpoints, which are a regular staple of Palestinian life, must be crossed in order to travel anywhere outside Ramallah (and many other Palestinian towns). It can, potentially, mean being held up for hours in queues—or turned back—while waiting to move between Palestinian towns for business, or to connect with family.

As rationalised to the international community, Israeli soldiers at these checkpoints are there to serve the security needs of Israel. In reality, however, they do little more than frustrate and humiliate the local peoples while securing the needs of the ever-encroaching Israeli settlements. As one Palestinian man put it to me:

It is not about security, there is always a way around. They are doing it simply to frustrate us, to try to get us to leave our land.

I wish I could say that my experiences proved this to be wrong or naive but they did not.

Creating art within such a context comes with a particular and unavoidable baggage. Watching rehearsals for Access Denied was a fascinating insight into how dance can marry the expression of the political and the personal within daily life.

Maysoun once said with a sad smile: "Well now we Palestinians will soon have our Wailing Wall". She was referring to the new ‘security wall’ being built around Palestine—and inside the Green Line of 1967, the UN recognised border.

Thus a wall features heavily in Access Denied, as do checkpoints. There is even a prison dance depicting torture, created by one who had been held in administrative detention for six months. 1

But then, away from the overtly political references to the occupation, Access Denied gives us love duets. In one the lovers dance with each other from opposite ends of a pole, which, while cleverly restricting the possibilities of their personal contact (a culturally sensitive issue), in no way diminishes their intimacy. Other duets and ensemble pieces use props such as walls, barricades, tables and benches to fascinating effect.

Since returning to Australia and my comfort zone, I have felt a strange sense of displacement. I feel oddly guilty about leaving, as though it were my people I was walking out on. While I am loath to apply my limited pseudo-psychological analytic skills to why this is so, I am willing, precociously, to speculate that perhaps this is a little of what keeps Nicholas and many others in Palestine, fighting in their own ways to bring about change: guilt that while we with foreign passports can move with relative ease across checkpoints and borders, those we have met, and whom we now value as welcoming, generous friends, cannot.

In some sense I feel I have fled with my bag full of stories, abandoning the others to their fates while I return to parade and trade my stories to a world thirsty for the sensational, hungry to live vicariously through the episodes and prime-time slots of others. Perhaps this is why I feel such a reluctance, an uncomfortable hesitation, to tell my ‘stories’; that I grit a little when people innocently and good naturedly ask how was it, what was it like, eager to hear some first hand report, thinking perhaps that this dancer might be able to shed some insight onto this tragic ever-recurring news story.

I can’t. I really wish I could. I have my view, my bias, much of which you would have gleaned from the preceding paragraphs. But I have little to offer by way of wisdom as to how to resolve the ongoing conflict.

Burnt out car in the streets of Palestine. Photo: Josef Brown

Burnt out car in the streets of Palestine. Photo: Josef BrownWhat I do know, what I have seen and clearly experienced, is that people are still managing to get on with their lives. They are still making dreams and plans, caring about their present and about the stories of their past. They continue to possess and/or create hope for and in their children, a hope that yearns for a better, a more noble and compassionate world. I can tell you that amid the many stories of catastrophe there exist compelling stories of hope, love, success and inspiration.

A strange place, this so called ‘Holy Land’: eerily beautiful and—somewhat ironically and unexpectedly—timelessly peaceful yet torn asunder at intervals and geographical points and thus offering no deep rest. I pray the prayer of the non-believer and hope for a more merciful year ahead.

I thank the people of Palestine, the dancers of Ramallah for their generosity of spirit and honest, open hearts. I thank them for their art—their art that endures, persists and carries within it the expression, inspiration and dreams of so many.

Postscript

In part due to the controversy that has been stirred, particularly in the United States (which I witnessed first hand during a recent tour), with the opening of the smash-hit Hollywood film Passion of the Christ, and in part because, in my experience, there appears to be some confusion, I would like to clarify what I believe is an important point. To be against the Israeli occupation of Palestine—and I am—is not synonymous with being against the Jewish people, the Jewish faith or even against the just desire of the Jewish people for a homeland.

The argument at the heart of the Palestinian/Israeli conflict is neither ethnic nor religious, but about justice and law. It is about land and under what conditions, if any, one people is just in appropriating the land of another. In Australia our own issues of ‘land’ still burn. Indeed, I discovered as part of this journey just how much Australia’s issues with land parallel many of the problems found in the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, though time and demographic differences have created somewhat different paths for the conflict.