For some years, dance staff at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) has observed that too many first year dance students have difficulty adapting to the demands of full-time dance training in the tertiary context. To address this challenge for students, dance teachers/researchers at QUT have developed the Transitional Training Program (TTP). TTP is undertaken by all first year dance students in their first month of university study. The program recognises differing patterns of learning and practice, seeking to reveal those that hinder progress, and offers alternative approaches, which promote effective repatterning for improved practice. TTP establishes a holistic approach to learning by illuminating connections between intellectual and kinaesthetic understandings. This enquiry is embedded throughout the curriculum of the Bachelor of Fine Arts, Dance, and reinforces a scaffolded continuum of analysis and discovery for enhanced learning.

Maximising student learning at QUT

Brief history

Dance courses at QUT were developed in the early 1980s using traditional tertiary models from the UK and USA. There was no entrenched history or allegiance with existing courses, dance companies or staff and this allowed us to develop modern and innovative courses that responded to industry needs in Queensland and Australia. The philosophies and practices embedded during those years have continued to allow good growth and development, keeping QUT courses at the forefront of tertiary dance programs.

The dance staff has been first movers in adopting innovative professional development initiatives (collaborative practices, teaching exchanges, cycles of peer review, national and international workshops and conference participation etc.) to upgrade their teaching and learning practices. These efforts to effect change have connected positively with both staff and students and resulted in improved delivery of curricula. For instance, the Levels System (four graded steps of technical skill levels) in both ballet and contemporary dance technique study was implemented in 1988 to accommodate individual learning needs, regardless of the student’s own year of study, course or pathway of learning.

Adjunct support services facilitate and enrich knowledge transfer between scientific and artistic practice, and between educator and student. For example, the PASS (Peak Achievement Skills and Strategy) team at QUT currently comprises a physiotherapist, sports psychologist and massage therapist (all with backgrounds in dance) who support and augment the teaching and learning processes and experiences. Data received from these services has informed content design of TTP.

Student characteristics

First year students present educators with a very specific set of issues which influence their capacity to manage different learning environments and acquire functional self-management and motivation skills. Whilst all commencing students gain entry because of their potential for learning in the field, many have trouble adapting to the demands of an increased workload in full-time training. Typically they fatigue quickly, are unaccustomed to concentrating for sustained periods of time, are easily distracted and often resist change. Together this can stall a student’s learning, limiting their potential. There are a plethora of viable explanations for these behaviours and precautionary measures needed to be introduced to facilitate effortless, injury free transitions into the pre-vocational university environment.

The characteristics of student populations shift with generational change. Research about our current (2004-2008) first year students known as Generation Y, the children of Baby Boomers, tells us that they ‘have not really had to “want” for anything, and this has impacted on their work-life balance. Boomers and older Gen X’s live to work, while the Gen Y’s work to live—and this attitude alone suggests a big difference’ (Manpower Services, 2007, p. 2).

This has implications for a tertiary dance course where learning in both kinaesthetic and intellectual domains is required. Gen Y students have easy and often unlimited access to a constant influx of information which excites interest and enables immediate engagement and consumption. However, when learning flows from sustained practices across time, building incrementally over months rather than weeks or days, and outcomes are seldom immediate, then the ‘work to live’ ethos does not always complement these longer time frames required for learning in dance.

Gen Ys are techno-friendly and highly conversant in communication and gaming technologies.

(B)ecause of their reliance on technology, they believe they can work flexibly any time, any where and that they should be evaluated on work product, not on how, when or where they got it done (Manpower Services, 2007, p. 2).

This observation suggests that many of our students are more likely to seek and value outcomes over process, a habit of mind, which can undercut sustained time commitment to learning practices. Sometimes this attitude generates a gap between knowledge and experience, theory and practice and a separation between mind and body. For example, while many students can articulate the components and importance of a warm-up, they do not practise this routine activity and nor could they explain the safe practice of many elements of the ballet technique.

These practices and behaviours are challenged in TTP, for the complexity of information and kinaesthetic experience requires sustained focus and concentration embedded into curricula.

Introducing the Transitional Training Program (TTP)

History of TTP

The TTP was developed in response to these overarching issues. It was clear that how we presented information was as important as what we presented. How could change be expected when students continued learning in the same familiar class structures, only now with different teachers? In order to initiate change for life-long learning, we needed to encourage embodied learning and kinaesthetic understanding through experiential workshops and laboratories.

The intent of a dance class is to develop the movement vocabulary or a specific idiom (i.e., ballet, modern, jazz) and therefore, it is not within the scope of class to provide adequate time for the development of strength, endurance and flexibility for all muscle groups. (Grossman & Wilmerding, 2000, p. 120)

Despite research and despite Gen Y trends, the prevailing thinking of many dancers is still that a dance class should give you all that you need, so the more classes that you do, the better you become. In reality, mindless repetition will not improve things and there is simply not enough time in a single one-and-a-half-hour dance class for a teacher to respond to the myriad of technical and artistic needs presented to them and then implement individually tailored fitness and cross-training sessions. In fact if we are serious about re-educating the dancer, freeing them from non-functional habitual physical patterning and allowing for new thinking and practices, we have to alter how we approach their training. As Marika Molnar (in Smith, 2001, p. 68) says:

The best way to change their habits is to educate them. Many dancers have grown up under the misconception that cross-training is bad for them, that they should focus only on dance. But they need to realise that their bodies have to be allowed down time and alternative exercise that accentuates different muscle groups.

Information shaping content selection for TTP came from several areas: data from injury records since 2000 collated by the Dance Program’s PASS team, elite performance training information from sport and dance research, feedback from students and anecdotal information from teaching staff.

The design of TTP embraced three dimensions:

- Learning in Transition

- Physical Training in Transition

- Teaching for Transition.

The focus was to empower the student and create effective entry points for common understandings in the learning and teaching of dance techniques for improved and accelerated learning outcomes.

In 2004, it was decided that TTP would run for the first three weeks of semester for all incoming students. The plan was to suspend formal training for these three weeks and build an alternative program of work. This period in which traditional dance training was suspended, created time and space for the body to experience adjunct areas of physical practice whilst relieving ‘patterns of holding’ that may be detrimental to the advancement of their technical learning. As staff, we felt that the ‘best place to break this potentially destructive chain is at the beginning; the dancer will benefit from early detection of inefficient movement patterns and increased awareness of the functional possibilities’ (Minton, Solomon & Solomon, 1990, p. 177).

The staff was supportive, yet managing students expectations of study at QUT was more difficult. We knew they would be expecting dance classes from their first day at university and so non-dance classes would most likely be seen as a poor and impoverished alternative. Student feedback in 2004 reiterated this with requests for the integration of dance classes to TTP.

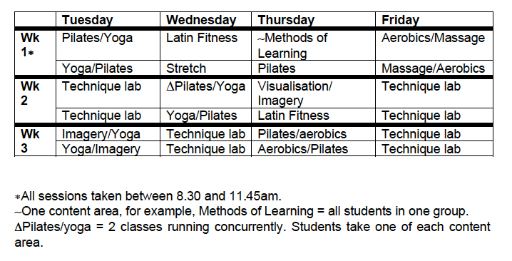

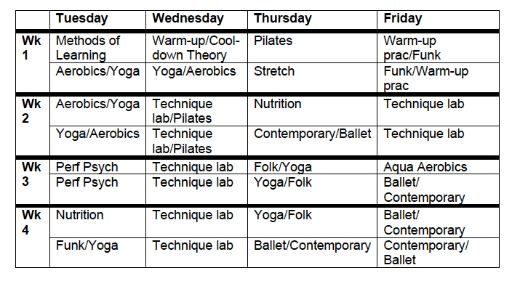

TTP now, in 2008, runs for four weeks and dance technique classes are integrated at a basic level from week two. A shortened version of TTP is currently being offered in response to student demand, at the commencement of Semester Two for all students, Years 1, 2 & 3. The following TTP Plans give an overview of changes from 2004–2008.

2004 TTP plan

2004 TTP plan 2008 TTP plan

2008 TTP planSpecialist Pilates’ instructors, yoga instructors, sports psychologists, masseurs and physiotherapists with dance backgrounds deliver the program. These practitioners are able to combine their industry expertise with their dance experience and provide highly specialised programs which support our philosophical approaches to TTP. In instances where the desired teachers are not available, the program is adjusted to ensure quality of information and delivery is maintained. For example in the 2008 program Imagery/Visualisation class was replaced with an extra nutrition session.

Learning in transition

Many students enter tertiary training expecting that their learning will continue in a similar mode to their secondary schooling and dance studio experience. The danger is that mindless replication of learning patterns can be reinforced. TTP challenges this in the Methods of Learning session by introducing an analysis of learning behaviours and patterns, teasing out the hindering from the helpful. For example, the concepts of ‘good class’ and ‘bad class’ are openly debated and the students share a range of opinions that either supports or challenges their own learning experience. These discussions cover a broad spectrum of topics including how they, as students, emotionally approach class, what determines their concept of hard work, how music is used in a class, how corrections are given and received and how verbal and non-verbal languages are used. In short, discussion centres on what constitutes an effective class for them and their learning. Revealing individual learning habits and preferences, exposing them to analytic scrutiny and then investigating alternative models for learning and practice provides the opportunity for the student groups to experiment in a supportive environment.

Students are encouraged to reflect on their own patterns of muscle engagement and use such knowledge through guided practice and observation of peers. For many this reflective process is revolutionary and/or a positive learning experience. A few students found the approach boring and confusing but the time allotted (each technique lab lasts three hours) allowed good individual feedback opportunities and information was reiterated later in formal units of study in the course.

The students for whom the information was new had either not had the same levels of attention in a class prior to coming to QUT or had heard the information but were unaware that they were not practising that information in their bodies. Those for whom it was confusing either had difficulty connecting their cognitive understanding with their kinaesthetic apprehensions or experienced contradictory information, which did not confirm their prior learning.

Performance Psychology skills training introduces reframing and goal setting techniques to help students consider ways of being successful as students in their transition to and continued engagement in university life. This information is then developed in the second year of the Bachelor of Fine Arts in a more formal unit of study. The TTP discussions promote self-reflection and help prepare students to enter into and take better control of their new learning environment.

Physical training in transition

In designing this transitional program dance staff embraced the philosophies of cross-training. There is sufficient research now to support this approach and we know that appropriate ‘supplementary off-studio exercise training can, indeed, increase muscular strength without interfering with artistic and dance performance requirements’ (Koutedakis, 2005, p. 6).

According to cross-training principles, the movement principles underpinning TTP address stretching, strengthening, fitness and introduce students to principles of overload, rest and graduated work load. All sessions in Pilates, yoga, aerobics, massage and technique laboratories integrate anatomy and alignment information with adjunct classes in the use of imagery and visualisation techniques. The number of staff teaching into the program is kept to a minimum to lessen confusion created by differing use of language. Following is explanatory information about areas of content in the Physical Training aspects of TTP.

Aerobics

Aerobic fitness is an important component of TTP as much research concludes that dancers are not as fit as they should be and that improvements in this area will see a decrease in injuries and increase a dancer’s productivity and longevity.

Koutedakis and Jamurtis report ‘[t]he relatively small aerobic fitness increments measured in professional dancers are not related to their classwork but to the duration and frequency of their performances’ (2004, p. 652). There is, therefore, even less ability to improve fitness for students through regular class training within the thirteen-week-length of a semester, where performance is not a regular activity, but an end of the semester activity.

All students undertake fitness testing to measure incoming fitness levels as part of the TTP program. Although many students are surprised at having to undertake this test, they are not surprised at their less than satisfactory results. We have found that this test gives students a solid starting point from which to improve and, when repeated at the end of Semester 1, records their progress across the semester. Students are encouraged to continue two to three aerobic sessions per week as a life-long practice.

Fitness sessions in TTP are delivered in different modes to offer cross training opportunities and comprise: folk and Latin dance classes, funk and hip hop classes, aqua aerobics, aerobics, kick boxing and aero box. The importance of warm-up and cool-down practices is embedded through guided practice and students are encouraged to develop their own practice to cater for their individual needs and preferences.

Pilates and yoga

Astanga and Iyengar yoga and Pilates’ sessions offer strength and conditioning elements and support the technique lab content.

Massage

Sessions involving guided self and partner massage were introduced to embed anatomical terminology, promote body awareness and self-maintenance and create balance in busy lifestyles.

Imagery and visualisation classes

These classes are used to assist understanding the physicalisation of technical principles and develop qualitative responses from the body in movement. ‘It has been shown that mentally practicing a skill (the act of performing the skill in one’s imagination, with no action involved) can produce large positive effects on the performance of the task’ (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott, 2007, p. 39).

Technique labs

The links between core stability information offered in Pilates classes and individual areas of difficulty observed in technique class are carefully unpacked for the students. The labs reveal destructive holding patterns and technical and anatomical habits within both ballet and contemporary techniques. Using reflection as a tool, students are encouraged to examine their approaches and practices. Students are discouraged from unsafe manipulation of their body to fit the demands of any technique. Each session seeks to reveal holding patterns that hinder progress and offers alternatives to release the old and integrate new understanding into their physical practice.

Teaching for transition

TTP presents an ideal opportunity to in-service staff who will continue the learning process initiated in TTP in their own classes. Staff members undergo this in-servicing in tandem with TTP. Students’ misunderstanding of terminology and language is fed back to staff along with technical concepts that have been examined in the technique labs. This provides staff with fertile ground for discussion and learning. Some of the technical issues that arise are: use of rotation, working heels together in first position, what happens in a plie, and arabesque, how to work in parallel, scapula stabilisation, backbends/high release, use of breath.

Staff revisit teaching styles and approaches, discuss the development and delivery of class content and the use of language and terminology in the teaching process and have built a word bank to be shared across genres. The use and meaning of language is examined and analysed and replaced with newer terms or more precise ones. Students are encouraged to move away from phrases like ‘tuck under’, ‘suck in your stomach’ and ‘straighten your spine’ and replace these with language, questions and images that are more anatomically correct and biomechanically efficient. For example, ‘neutral spine and pelvis’ and ‘relax your ribcage’.

It is recognised that we all teach in different ways and this is regarded as an advantage in the delivery of our curriculum. What is shared however is a constructivist attitude to our teaching and this was pivotal in directing the design of TTP to offset traditional training regimes.

The constructivist encourages students to use whatever experience, knowledge, and mental frameworks they bring to school, while guiding them in the formulation of newer, more powerful frameworks and concepts in order to assimilate and accommodate the subject matter of study. (Fenstermacher & Soltis, 2004, p. 40)

We could see no advantage in tearing down students’ prior learning and experience. Instead we set out to offer alternative concepts and nurture thinking processes, which would assist students to reframe and build new knowledges for more powerful learning outcomes.

Outcomes

Outcomes for students

Yearly student surveys have resulted in a significantly large proportion of the students (81-93% across all years of delivery) recognising the value of TTP and remaining committed throughout the process. One continued comment about technique labs was that they wanted them in smaller groups with more individual attention. Whilst this suggests a desire to work correctly, it also points to problems for students in trusting their biofeedback mechanisms, transferring critical feedback from other students to themselves and processing information on a kinaesthetic level.

Whilst many attempts to address this issue have been made, including two staff tutoring each group at the one time, as well as buddy system feedback mechanisms, hands on biofeedback, demonstration exampling and different methods of group management, the comments persist. The inability to focus and remain attentive for prolonged periods of time is one of the Gen Y characteristics and is difficult to accommodate when concentrated attention is needed to master quite subtle conceptual and perceptual information. This lack of capacity to attend is the main difficulty staff experience in the delivery of this program.

An emphasis has been placed on developing and encouraging a mind set that will enable information to be transferred into alternative settings for practice and learning throughout life. The relevance of autonomous and reflective learning for future career success and longevity was highlighted by over 50% across all years as the top value outcome of the program.

Students named Pilates, yoga and aerobics as their top three most engaging activities in 2004 & 2005 with Pilates, yoga and technique lab in 2006 and technique lab, aerobics and Psychology of Learning in 2007 and technique lab, aerobics and funk in 2008. We suspect Pilates has dropped off the list because of the increased availability of classes offered locally in Brisbane and across Australia. When asked ‘What are three of the most significant things you have learnt during this program’, the top responses from each year all named core stability information and practice, increased body knowledge and awareness and alignment issues around pelvic placement.

Outcomes for dance at QUT

It is rewarding to note that many students understand and value the impact of this program on their current and future learning. One student teacher of dance, for example, perceived that ‘I can pass the information I learnt to the students that I teach so that eventually (hopefully) there will be more and more students that are knowledgeable about dance practice’ (Respondent 4, TTP Questionnaire, April 2008).

Although the statistics for injuries are inconsistent, in that not all years demonstrate fewer injuries in second semester compared with the first, what staff have noticed is that fewer students have missed exam and performance periods because of injuries. This is a recognisable improvement. We have observed positive change in the area of injury prevention and management with students and staff being better informed about prevention mechanisms and rehabilitation programs: ‘[The program] really focused in on the body’s correct alignment and taught me a lot about what I was doing to my body which was actually bad for me and promoted bad posture and injury’ (Respondent 12, TTP Questionnaire, April 2008). Students who carry chronic injuries are exposed earlier in the course, allowing the PASS team and staff to implement positive rehabilitation strategies. The massage therapists in particular have noted that more students are using massage as a preventative tool and there are fewer injuries necessitating the interruption of study pathways.

It has also been noticed that students are able to engage in analytic dialogue with staff and their peers from a much earlier stage in their training which has fast tracked their learning. Many students are moving into Level Two by the end of their first semester of study rather than after their first year of study. Improved communication skills, reflective skills, strength in core stability and a greater appreciation for and acceptance of the individual body’s potential have all contributed to this development. These skills also provide a secure grounding for effective learning in many future units of study technically, creatively and intellectually.

TTP allows students themselves to identify areas of strength and weakness in their work and sets the scene for future training expectations. Teaching staff now spend less time establishing clear and correct principles for safe dance practice and anatomical, technical and stylistic fundamentals. Shared understandings of language have lessened confusion over terminology, positively affecting class content and learning outcomes. As a result of all the changes, course expectations are more transparent for both students and staff.

Conclusion

Although there is a need for conclusive empirical data in this field, the experience of QUT dance staff will attest to the value of TTP as it has been implemented across the past 5 years. Difficulty with establishing control groups will always be problematic for any formal research with such a program as TTP, yet QUT Dance remains confident of the efficacy of this program which will continue to shift and respond to meet the demands of evolving student populations.

References

- Fenstermacher, G., & Soltis, J. (2004). Approaches to Teaching. NY & London: Teachers College Press.

- Grossman, G., & Wilmerding, M. (2000). The Effect of Conditioning on the Height of Dancer’s Extension in a la Seconde. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 4(4), 117 – 121.

- Jamurtis, A., & Koutedakis, Y. (2004). The Dancer as a Performing Athlete: Physiological Considerations. Sports Med, 34(10), 652.

- Koutedakis, Y. (2005). Cardiorespiratory Training for Dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine and Science, 9(1), 6.

- Manpower Services. (Australia). (2007). Generation Y in the Workplace Australia. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.manpower.cz/images/GenerationYintheWorkplace.pdf

- Minton, S., Solomon, J., & Solomon, R. (Eds.). (1990). Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. VA: American Alliance for Health, Recreation and Dance.

- Shumway-Cook, A., & Woollacott, M. (2007). Motor Control. Translating Research into Clinical Practice (3rd ed.). Pennsylvania and Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Smith, L. C. (2001). Niche practices: performing arts. Magazine of Physical Therapy, 9(2), 68.