It is very fitting that the inaugural Dame Peggy van Praagh Memorial Address should be delivered at this gathering. We are very close to the first anniversary of Dame Peggy's death which occurred in Melbourne on the 15th of January last year. I regard it an honour and a great privilege to be the first in what I am sure will become a long line of dance artists and scholars who will pay tribute to Peggy van Praagh in this way.

As most of you know, Dame Peggy was a founding member of the Australian Association for Dance Education (AADE) which was established at a National Conference in Melbourne in 1977. It is not so well known that the seeds of the AADE were first sown in 1974 at Armidale in northern New South Wales at the University of New England's Summer School of Dance, where Keith Bain, Warren Lett and I were members of the faculty, and Dame Peggy was presiding over one of the celebrated choreographic workshops.

I have written elsewhere of the early influences in her life, 1 one of which was the master choreographer, Antony Tudor, and another the pioneer educator of "Summerhill" fame, the great A.S. Neil. It is little wonder that her interest in the development of young choreographers was equalled by her concern for the promotion of educational programmes in dance.

In the latter part of her working life she made many contributions to the growth of tertiary dance studies throughout Australia, notably here in Western Australia at the Academy of the Performing Arts.

Dame Peggy's life and work have been so well documented since her death that it is unnecessary for me to repeat the story again. She would have much preferred to talk about choreographers making dances, especially Australian choreographers making dances, so much so that I can almost hear her saying "Oh darling, do let's get on with it." So that is what I propose to do.

Over the next few days the question "what is Australian dance?" will be posed in many ways. We will no doubt seek to define what we mean by the question as well as make many attempts to answer it. This paper endeavours to deal with the question of our identity—as Australians who also happen to be dance artists.

We know that our experience has been shaped by the fact of living in this land. It is a unique land in every way. Judith Wright, one of our most esteemed poets, has remarked, "For Aborigines, every part of the country they occupied, every mark and feature, was numinous with meaning." 2 The spirit ancestors had walked the land, creating as they went a 'Dreamtime' in which past, present and future were inextricably entwined—and the land remains invested with their presence. Our own reality is different.

No word exists in our language for the complex of earth and sky, water, tree and spirit-human which is the Aboriginal world. Neither our language nor our culture permits us to relate to the world in this way and I think we are all heirs to this western impoverishment of spirit. And yet we know that in some ill-defined way we belong also. How else can it be? For some of us it is an adopted country.

Our ancestors now come from the four corners of the earth, but for all of us it is our shared homeland. Although most of us live in large cities on it's coastal plains we know that we sit on the doorstep of a thousand miles of open space.

Our immediate ancestors would have called it empty space. Only artists, it seems, have been able to give us our bearings. It is a space which Australian painters have invested with their own mythology, both personal and ancestral. Patrick White's Voss saw the harshness of it's sticks and stones and rocks as a metaphor for his own austere spirit. Our film makers, too, have made it's images readily available. I believe that dancers also know it, as they know many things—in their bones and nerves and muscles. Space is our natural environment: we have more of it than almost any other nation on earth.

For several months in 1990 I had the good fortune to travel around Australia (with the assistance of an Australia Council research grant) in order to ask a lot of questions of a number of our most distinguished choreographers. The answers to these questions are now recorded for posterity and lodged in the Oral History archives of the National Library in Canberra.

While talking to the choreographers I also saw many dances, some of them as many as five times, and all of them without exception "Australian Made". Very few of the choreographers actually thought of their dances as peculiarly Australian. Certainly there was a vast range of styles as well as of forms and contents. It seemed significant to me, however, that the notion of themselves as ' Australian' artists was pervasive.

So what is it I wondered that makes this so important to us, for I am sure we can all identify with the sentiment. Let us consider it for a moment in the light of my comments about the Australian landscape and our relation to it.

Most of us are familiar with the perception of Australian dancers as consumers of space, dancers who are at ease with lots of space as dancers of many other western nations are not. Every Australian dancer who has spent time overseas is made aware of this perception very quickly; the comment "you must be an Australian" is made as soon as the dancer is given the opportunity to move. Australians, it seems, move as if they own the space.

So where does it come from? Is the answer as obvious as the fact that we invariably have more room in our studios? Perhaps, but then we like the image, don't we: it fits our feeling about ourselves, it seems right, and when I think about it further I remember how my European friends always remark on Australian skies, the vastness of light and space, the distance of the horizon—and straight away we are there, led by our need for an identity, to a mirror which shows us what we would like ourselves to be; as though our landscape is our chosen image of ourselves.

When I examine my own feelings about this I know that I still have in my imagination the wonder of childhood experience in the bush and near the ocean. I think this is a common experience for a generation of Australians who grew up in the thirties and forties as I did. But the choreographers I have studied tell me much the same story, and their generation is often two decades younger than mine.

For many of us, the Australian landscape seems to be both an experienced reality and a poetic construct, a potent symbol of our spatial predicament; an unlimited source of powerful metaphors for the satisfactions and frustrations of our spirits.

Perhaps we will never acquire that deep affinity with the land which is the heritage of the Aboriginal people. In my mind, however, there is no doubt that our imaginations are being shaped by this land in ways which "we" do not always fully apprehend but which are recognisable to those whose experience of space is entirely different.

I have commenced this talk with this view of our homeland (or our adopted country as the case may be) because this is the reality of where we are and who we are, a nation of only seventeen million people living on the fringe of a country the size of Europe. Our preoccupation with space is not an indulgent fancy: it is the truth of our daily lives which colours every dance which is made in Australia. It is the source of our greatest distinction, and the cause of our major dilemma.

In May of last year when I commenced my research, I had little idea of the way in which my perceptions would be changed by the journey itself. In Townsville where I began, Dancenorth is a company of only six dancers. The artistic director is also rehearsal director, teacher, promoter, choreographer, and experienced ambassador. Her company tours regularly around a huge state and travels as far as the Pilbara in Western Australia and to Alice Springs, Darwin and Brisbane, as well as many places in between.

This is an area which is larger than the rest of Australia put together. Dancenorth is the only professional theatre company north of the Tropic of Capricorn. Cheryl Stock is one of our most experienced dance artists and her company's current repertoire contains works by Graeme Watson, Natalie Weir, Helen Simondson and Cheryl herself.

In contrast to Dancenorth, Tasdance based in Launceston is practically in the outer suburbs of Melbourne which it actually manages to visit once a year. It's not that Tasdance couldn't find the time or the will to do it more frequently, it's just that the cost of the journey is prohibitive if Jenny Kinder, the artistic director, is to carry out the company's commitment to provide Tasmania's school children with a quality dance experience—for this takes most of the year.

I mention these two small companies which are located nearly three thousand kilometres apart because they are similar in size and operation. Jenny and Cheryl have been friends since their meeting at Armidale in 1976 when Cheryl danced in a small work created by Jenny for a choreographic showing.

I know that they have never seen the work of each other's companies. The space which separates them has become a chasm and the cost of bridging it is not an option currently available. Undertaking a journey which is greater than the distance between London and Moscow is not something one can do on a regular basis. If either of these companies want to see the work of the Chrissie Parrott Dance Collective in Perth, the problem is compounded.

I am aware that in Western Australia, dance people feel that they are deprived of the stimulation which is available to their peers who live on the east coast. But for all of us, even those dancers and choreographers who live in Sydney or Melbourne, the 'tryanny of distance', as Geoffrey Blainey has so aptly put it, is a major source of the sense of isolation from which we all suffer. A person of my age living in New York all her life as I have done in Melbourne, would by now , have seen all the major works of the twentieth century, including those from England and Europe. Exposure of this kind is something we simply do not have.

In my own experience as a modern choreographer in the sixties I know that my sense of aloneness was very acute. Those of us working at that time depended on the occasional visit of an American company to see what the dances we were reading about actually looked like. Classical dancers and choreographers were better off.

A much longer tradition, which included Adeline Genee and Anna Pavlova, brought the Ballets Russe to Australian cities in the thirties. Helene Kirsova in Sydney and Edouard Borovansky in Melbourne established companies in the early forties. The expressionist dance of central Europe came to Australia in the thirties also. By 1939 Gertrud Bodenweiser had established her school in Sydney, and Hanny Kolm (now Exiner), a member of her company, had joined her friend Daisy Pirnitzer in Melbourne to teach and perform. It was this school in Melbourne which introduced me to the new modern dance in 1940.

It is not my intention to turn this paper into a history lesson but I am endeavouring to note the sources which have provided the major choreographic inspiration in this country and how the twin themes of isolation and convergence influence the way in which our choreographers work.

Few of us in the forties and fifties had the resources to take us overseas. For an exceptional talent, the ballet world provided more scope, and most of our early choreographers had their first experiences in London, as did Robert Helpmann and later Laurel Martyn and Dorothy Stevenson, who both created works for the Borovansky Ballet.

Laurel Martyn's Ballet Guild, established in 1946, eventually became Ballet Victoria and was a major contributor to the growth of choreographic awareness, at least in Melbourne. Laurel herself created many significant works which used Australian dancers, designers and musicians in ways not previously open to them. The convergence of these various artists resulted in a kind of "creative broth" and what emerged very quickly was an innovative company with high standards of performance and a considerable degree of public support. Other pioneers, like Charles Lisner in Brisbane and Kira Bousloff in Perth, were also choreographers who created small pockets of creativity, by inclination as well as by necessity.

For modern dancers, the sixties proved to be a kind of coming of age—a decade of growing awareness of compositional techniques. A group of young dancers in Sydney, which included Graeme Watson, Chrissie Koltai and Jacqui Carroll, were beginning to make work, and in 1969 Nannette Hassall won the first Ballet Australia choreographic competition and used her prize money to go to America to study at the Juilliard School in New York.

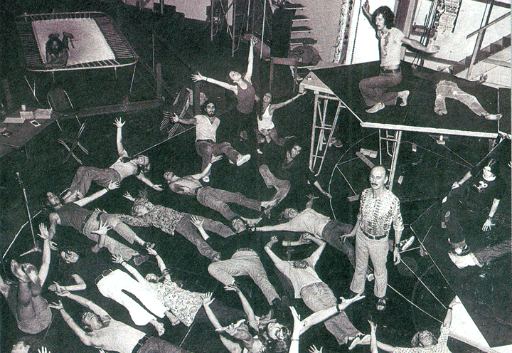

Keith Bain rehearsing the cast of Jesus Christ Superstar, 1972.

Keith Bain rehearsing the cast of Jesus Christ Superstar, 1972.Director: Jim Sharman Choreographer: Keith Bain

Keith Bain who was both teacher and mentor to many of the young moderns in Sydney at that time has commented on the creative ambience which was in evidence among the young dancers who took classes at the Bodenweiser studios. Similar developments, starting in 1963, were taking place in Melbourne within Margaret Lasica's Modern Dance Ensemble and my own Contemporary Dance Theatre, and in 1965 Elizabeth Cameron Dalman established her own creative broth in the Australian Dance Theatre in Adelaide.

It was in the Australian Ballet, however, that Peggy van Praagh's policy of developing new Australian choreographers finally began to make a difference to the 'national' scene. It was here that Garth Welch had his first opportunity to create a work. Garth has commented on his desire to look at something had made as opposed to being the passive recipient of other artists' works, although he is the first to acknowledge the debt he owes to those who taught him the elements of the craft. His first work was Variations on a Theme, made in 1964. When he returned from a year's sabbatical in the USA in 1967 he made Othello, a work so admired that it has been performed by companies throughout Australia ever since.

No account of the development of choreography in Australia could ignore the influence of Peggy van Praagh. All the choreographers who had contact with her during their formative years speak of her interest and her positive encouragement. What really mattered was that Dame Peggy valued both the creative process and the product—a dance which could be interpreted and performed by dancers.

She was interested in the growth of the art form and in the young artists who were prepared to work long hours and in difficult circumstances to make work for a choreographic showing. In 1971 the results of 'Australian Ballet Choreographic Workshop' were shown in the Princess Theatre in Melbourne. Listed in the program were works by John Meehan, Wendy Walker, Don Asker, Ian Spink, Graeme Murphy and Leigh Warren; a creative broth if ever there was one. Meryl Tankard made her first work for a similar event only a year or two later.

I believe that the choreographic workshops which were held at the University of New England in 1974 and 1976 were also seminal events in every sense of the word. Dancers, choreographers and musicians came from all over Australia and for the first time, I think, recognised that their experience as Australians was important to their development as dance artists.

A group workshop at the 1974 at UNE. Shirley McKechnie (at the piano) is leading the class.

A group workshop at the 1974 at UNE. Shirley McKechnie (at the piano) is leading the class.When I tell you that Garth Welch, Jacqui Carroll, Ian Spink, Paul Saliba, Julia Cotton, John Meehan, Rex Cramphorne, and Stephanie St Clair were among those at the 1974 school you can begin to assess the impact that these artists had on one another, especially as they all filled the dual role of both dancer and choreographer.

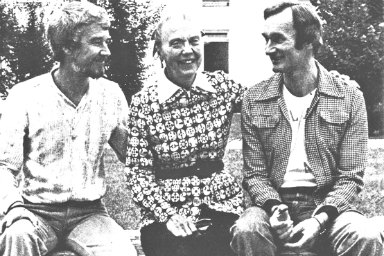

In 1976, the last year of the Armidale Summer Schools, a distinguished faculty included Peter Brinson, who is to be honoured by the AADE at this conference for his contribution to the founding of the organisation. It also included Norman Morrice, and Martha Hill who was then still directing the Dance Division of the Juilliard School in New York.

L–R: Norman Morrice, Martha Hill and Peter Brinson at the 1976 summer school in Armidale.

L–R: Norman Morrice, Martha Hill and Peter Brinson at the 1976 summer school in Armidale.Also at Armidale that summer were a number of people, who, beginning with Peter Brinson's course in Dance History and Criticism, have since made important contributions to the beginnings of Australian dance scholarship. But perhaps most significant of all there were young dancers from all over Australia and a number of choreographer-dancers as well.

Two young artists who created enormous interest were Graeme Murphy and Nannette Hassall, both in the early stages of their choreographic careers in 1976. Carl Vine was a composer in residence; his first collaboration with Graeme Murphy was on the New England campus. For everyone present the excitement was pervasive. Fresh ideas came from all directions. The creative broth, New England 1976 was a memorable one. It bubbled away for a good three weeks. 3

Both stimulation and transformation then, are at work when artists converge in this way, and it has seemed important to me to review some of the moments in our history when this has occurred. Working in the studio, as most of you can testify, brings all our powers into play, knowledge is passed from body to body by purely kinesthetic means, lots of talking too... "how does it seem to you?" or "can we try it this way now?"

It all seems so common-place now that we forget that this way of knowing is not always accessible to others. Many people, like athletes for instance, use movement as naturally and as easily as a dancer does, but it is only in dance that movement can comment on the nature of human experience, a part of which is the nature of dance itself.

When the ambience is right and artists feel safe to take risks, the creative ideas begin to flow together and enrich one another. Whenever this has happened it seems to me that a confluence of imagination and movement invention begets a synthesis which results in a harvest of riches for everyone involved.

I think it is important to remember that a nurturing milieu is one in which there must be freedom to fail. If lack of immediate success results in one being made to feel personally diminished, then it is likely that no more risks will be taken, and without risk there is no creativity. This applies whether the work is shown in a studio to one's peers or is given a full production for an audience of two thousand people.

Only the most experienced and proven are permitted to fail in this circumstance, and then not very often. It follows that the apprentice choreographer should be carefully nurtured and not exposed to unhelpful or ignorant criticism until the work is mature enough to stand on it's merits.

I have been speaking of some aspects of the creative broth—one of these is the process with which we are familiar in the guise of the choreographic workshop when the milieu is conducive. Another is the one which operates, when, in a particular time and place, artists are brought together by circumstances which favour their interaction and mutual support. Only in isolated instances as we have seen, has this happened to any degree in Australia.

A relatively recent example is the group of artists who worked under the name of Dance Exchange in the late seventies. Nannette Hassall, a prime mover in Dance Exchange went on to form Dance Works with a group of choreographer/dancers in Melbourne whose mutual concern was the exploration of new ways of making dance works. Beth Shelton, a foundation member of this group is now one of it's Artistic Directors. There have of course been others. Kai Tai Chan's One Extra Company is one which has been commented on at this conference.

Mickey Furava, Lee Lei and Kai Tai Chan in Ah Q Goes West, One Extra Company. Choreographer: Kai Tai Chan

Mickey Furava, Lee Lei and Kai Tai Chan in Ah Q Goes West, One Extra Company. Choreographer: Kai Tai ChanPerhaps the best known international example of choreographers who choose to work in what I have been calling a "creative broth" is the group which showed work at the Judson Church in New York from about 1961 – 1968. One wonders if they would have become quite so famous if Sally Banes had not written Terpsichore in Sneakers.

Many tertiary students might have been spared the conundrums of Trio A if she had been a little less enthused! One is reminded of another American advocate, the critic John Martin who invented the term 'modern dance' when he saw the results of the creative broth being cooked up on the Bennington campus in the thirties by those three truly awesome ladies, Martha Graham, Hanya Holm and Doris Humphrey.

In Australia we have no one great centre like London or New York or Paris to which all aspiring artists flock. Nor do we have large populations spread over relatively small areas as in Holland and France, which can provide support for a number of different groups. With Australia's population around one quarter that of France, and with a land mass fourteen times as large, it is clear that the parameters of our experience are vastly different.

In 1990 there were seventeen regional dance companies in France, all funded by a cooperation between the French government, the regions and the host towns. 4 In addition to these 'choreographic centres', the Paris Opera Ballet employs one hundred and thirty two dancers and thirteen apprentice dancers. All these companies are within easy reach of one another—at least by Australian standards. The prevailing wisdom is that France is where it is all happening. No wonder! The creative broth must be on the boil most of the time.

Fortunately we also have the Sydney Dance Company and the handful of even smaller companies spread around the coastline from Townsville to Perth on the fringe of three million square miles of a largely uncomprehended terrain. "The typical Australian" says Geoffrey Blainey, "has never seen the real outback. He imagines it. That gives the outback a firm grip on the minds of people." 5

Space and distance then, have shaped our imaginations and our images of ourselves. They have also shaped the way in which our dance has developed. Many of our artists feel isolated from the freely available convergence so natural for artists in other circumstances. Not infrequently, choreographers have spoken to me about their love for this country. They also speak of their hunger for the stimulation they took for granted in Europe or New York.

Most of our creative artists have felt this need at one time or another, but for dance artists, the problem is critical. Videos, important as they are, are no substitute for the dynamic presence of the dance itself. Instead of catching a bus to the other side of town, our artists must catch a plane to the other side of a continent. I think that this environment of separation and isolation over a long period of time has had some significant results.

One of these is the erosion of confidence in one's own abilities when faced with what appears to be a superior way of doing things—the typical colonial cringe. But there are positives too. Our dance artists have been among the most enthusiastic seekers of knowledge and cultural stimulation since the 'brain drain' was recognised as a national problem.

Fortunately for us, most of them came home. What they have done with this heightened experience in the past fifteen years has made Australian dance what it is today. I am so fascinated by this phenomenon that I am in the process of writing a book about it. I believe that both the character and ideology of the American and European models which have stimulated our dance artists in recent times have been substantially modified in this country.

Our choreographers have been drawn to styles and ways of working with which they have felt a special kinship, but on coming home have passed to students and other dancers their own particular interpretations of these, coloured as they inevitably are, by both early dance experiences, and the independence of thought and action which has been the legacy of an Australian childhood. The results of this process have been of a quality and diversity of which we may well be proud, for the new ideas have been filtered through some rather remarkable talents.

Somewhere in this equation the quality of Australian life and culture is an inevitable factor. While fairly static for most of our history, this is now changing very rapidly for all of us, regardless of where our ancestors were born. Surely one of the major tasks which face us in this last decade of twentieth century dance is to find ways and means of bridging both the space and distance between practicing dance artists in this country. We may speak of social distance, psychic space or political gaps, but what we finally mean is that our many and varied cultures do not readily learn from one another although the desire and will may well be there. For this we need as much energy, determination and vision as we can muster.

I believe that in the nineties this will be our major challenge. If we continue to turn our faces exclusively towards Europe or America we may just miss noticing the richness of the resources on our own doorstep. Surely we will have come of age when we choose to take up this challenge. I would like to conclude by suggesting that Australia will have a truly Australian contemporary dance when other cultures cross the oceans to find out about it.

For this we must continue to be part of the global culture, but in a way which contributes to it's diversity—by every means our imaginations can conceive. In my view, this could be the most exciting, and perhaps one of the most difficult challenges we have ever faced. If we can ensure that a share of our national resources, imaginative as well as material, are directed towards the making of our own creative broth, we may just find that we have transformed our spatial imperative into a spatial option.

A relatively recent work by Tasdance—Silverlining (2001)

A relatively recent work by Tasdance—Silverlining (2001) Choreographer: Chrissie Parrott

Dancers: Leanne Mason and Trisha Dunn

Photo: Paul Scambler