About the International Young Choreographer Project

The International Young Choreographer Project (IYCP) is held in southern Taiwan in July/August and is hosted by World Dance Alliance Asia–Pacific Taiwan chapter. A total of eight choreographers are chosen by WDA Asia Pacific (WDAAP) to attend.

Applicants are selected from a list of young choreographers recommended by World Dance Alliance (Asia Pacific, Americas and Europe) country chapters, based not only on their choreographic work, but also on their ability to meet the challenges of working in a foreign country with unfamiliar dancers and culture, and their potential as a significant contributor to dance in the future.

The selected choreographers work with selected dancers from Taiwan. The three-week process of developing new works with local Taiwanese dancers concludes with two performances. The program highlights the diversity of dance in both styles and cultures, and how local and international choreographers perceive their daily lives and the world.

The IYCP has been providing emerging choreographers with this invaluable artistic and cultural experience since 1999.

Australian participants’ choreographic experiences

2011: Zaimon Vilmanis

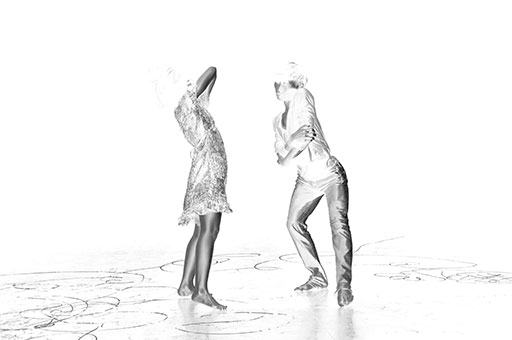

Zaimon Vilmanis choreographed The Absence of ToM. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.

Zaimon Vilmanis choreographed The Absence of ToM. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.My dancers in Taiwan were used to a more ‘directorial’ approach to choreography. I was constantly looking for ways to challenge the dancers and to show them I wanted to work collaboratively. Then I realised I could not expect them to understand my process in just three weeks. I had to make adjustments to accommodate their needs. My choreographic process with them changed dramatically. I had to take time to develop formulas which would help them to understand how I worked and feel safe in knowing that mistakes and failure were okay. Having taken more time to lead them through some of my choreographic processes, the students became more confident to ask questions and were willing to take more risks.

I have discovered that I have two choreographic processes. The first one was developed in a collective situation, where the collaborative input is evenly shared; the outcome is less of a concern. The second process is where I use more familiar formulas and choreographic tools that I can impose on the dancers and which relies on a clear concept that I can articulate to the dancers from the beginning.

Understanding this difference has strengthened my choreographic methods enabling me to adjust to new circumstances and foreign environments, to work under short time frames and with constraints. I now feel confident that I can successfully work outside my comfort zone and still enjoy myself at the same time!

Feedback from one of my dancers, Ming-Hsuan Liu, demonstrates the value of this cultural exchange:

“At the beginning of rehearsals, I had no idea of what Zaimon wanted. I concentrated very hard on the movements he taught. It never occurred to me that what he did was to make us used to his style first, and then let us rearrange the movements. This was my first experience of this choreographic method. Usually, the order of the movements, rhythm, and route are set by the choreographer.

“Since the work was not completely set, there was always excitement, spontaneity, and things beyond expectation each time we rehearsed. The rehearsals became more than repeating the same practice. I learned that dancing was more than a visual presentation for the audience. We could also learn from it.”

2009: Cadi McCarthy

Cadi McCarthy choreographed Behind the Veneer. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.

Cadi McCarthy choreographed Behind the Veneer. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.The project was a fantastic opportunity to exchange creative vision and artistic knowledge, and build friendships and long lasting connections with other artists. Although we spoke different languages, we all shared a passion for dance.

The project not only provided an opportunity to develop and explore ideas for a new work, but introduced new perspectives in dance through many and varied conversations, and the viewing of seven unique and outstanding works by international choreographers.

The project commenced with an audition process where 60+ talented young dancers pushed themselves for three hours to gain acceptance into the project. I was introduced to the dedication, generosity and desire these young artists had to be involved. After selecting six dancers (which was a difficult task as all the students were outstanding), the three-week choreographic process commenced.

The work we created, Behind the Veneer, looked at the fragility of interactions, the exploration of collisions in relationships, and the instability of continual shifting roles. The delivery of movement material and the precise and exact manner in which the dancers replicated movement language demonstrated the talents, precision and technical training of these young dancers. But how would I get the appropriate emotional intention across without language? This proved to be my ultimate challenge. However, with six dancers who demonstrated such dedication, enthusiasm, open mindedness, and mental maturity, the work quickly evolved and communication moved beyond words. I felt extremely lucky and privileged to be part of this process. The young dancers worked so hard and invested so much of themselves into the work it was a privilege to watch their development and understanding of the work.

The city of Kaohsiung also treated me well, the friendly nature of the people, the food, the culture and tearing along the busy streets, weaving in and out of traffic on the back of a scooter will stay with me forever and I hope I have a chance to return to Taiwan very soon.

I would like to extend my thanks to everyone involved in the project. It was an honour to work with you and I am a better person for being part of this project.

2008: Felecia Hick

Felecia Hick choreographed SAME. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.

Felecia Hick choreographed SAME. Photo: Zen-hau Liu.Initially, I was a little apprehensive about this project, as I was unsure of what was expected of me as a choreographer. I was also four months pregnant, so I was not certain how I would cope mentally and physically with the climate in Taiwan. I love the Asian culture and have travelled through many parts of Asia before, but had not been to Taiwan. I thought of it as place where ‘products are made’—not as a centre for the arts and dance. I was in for a big surprise!

The Taiwanese are generous, friendly and very accommodating of foreigners. I was warmly welcomed by everyone involved in the project – from the hotel staff to the Director Su-Ling and her hardworking staff at Tsoying High School.

I was unsure as to how I could use my limited time effectively in the studio, and how to communicate with non–English-speaking dancers – only one of my chosen seven could speak English! My way of working normally involves great trust, which can only be formed over a period of time, but I absolutely fell in love with my dancers and really enjoyed being with them in the studio.

As my starting point, I used the theme of a work that I had previously created, titled Beda (meaning ‘different’ in Indonesian), which came from a desire to explore cultural diversity. I liked to see how the Taiwanese dancers interpreted the theme. The new work was called Same and was completely different to Beda. I trusted my dancers and in turn they trusted me, and the result was a sensitive collaboration and cultural exchange between an Australian choreographer and seven amazingly proficient Taiwanese dancers.

AYCP provided a brilliant situation for a young choreographer. I learnt how to deal with the challenges and stresses of producing a work in unknown circumstances, in a limited time-frame, and with unfamiliar dancers. I was truly valued as an artist by the staff and dancers and did not feel the need to ‘prove myself’ to anyone. I have made lasting friendships and I cannot wait to return to this beautiful country with my baby in tow!

When in doubt, laugh (Brolga 30). To read more about Felecia’s experience as a participant in the 2008 Asia Young Choreographers Project (AYCP) in Taiwan.

2005: Elise May

The four weeks that I spent in Taiwan this year seemed to pass so quickly, that as I returned home I felt that I was leaving a huge part of myself behind in that lively, vivid, hot strange city—Kaohsiung. I travelled to Taiwan to represent Australia in the Asian Young Choreographers Workshop, run by the Jih Sun Foundation for Education, Taiwan as part of the World Dance Alliance—Asia Pacific program.

When I first arrived in Kaohsiung I knew I was in for a very different experience. I was told that in Kaohsiung, English speaking locals are a rarity, so just communicating with people was either a frustrating or humorous experience. Luckily I was rescued by Jack Gray, my fellow Maori choreographer on the project who came from New Zealand, and who knocked on my door to introduce himself on the second day. The connection we developed throughout the project was strong, and his wildly passionate creative energy pervaded our time there. After hours we spent a lot of time articulating, reflecting, resolving, supporting and exchanging with each other—it was like having our own private little debriefing sessions. We also spent many hours watching each other’s rehearsals, offering feedback and making observations.

At the initial audition/selection process I was taken aback by the very youthful enthusiasm of the dancers. Ranging from fifteen years old, right through to third year university students, their training seemed very balletic, yet their response to new ideas was vigorous and wholehearted. After a strange bidding/auction style selection meeting (the project co-coordinators sat around a large table calling out numbers and speaking rapidly in Mandarin, negotiating their desired cast), I was delighted with my carefully chosen eight dancers.

As soon as rehearsals began I knew that the dancers I had chosen would bring a real wealth to the work—I just had to find a way to communicate effectively, as we weren’t allocated a translator. I also knew that I needed to find a way to break through the ballet/ rigid modern dance training that seemed to be very present. I mostly used the approach of keeping the dancers engaged by moving, and spoke in English, only because it helped me to verbally express myself as I demonstrated. (I was told later that much of what I said could be understood, yet not responded to, as much of their experience of the English language came from watching western television.)

As a result my work evolved away from my original concept. I began to pursue things as they arrived, working more intuitively and really adapting to my lack of verbal expression by becoming more detailed and creative with the movement rather than obsessing over translations of meaning. I would usually create work from a conceptual framework, so this was really different for me.

I felt that the dancers’ response was one of commitment to the new sensations and kinesthetic concepts and they had a real openness and attack to their approach. I believe that their education system instills a sense of unquestioning respect for the teacher. In Australia, my experience with young dancers is that they are quick to verbalise opinions and questions, but I found with the Taiwanese, questions may arise but are less likely to be verbalised. This unquestioning quality made the dancers ‘sponge–like’ in their learning. I found them to be so committed and really self disciplined and creative. Yet I had the distinct impression that their natural creativity is under-utilised in their usual choreographic work. They really came up with some very complex and mature movement patterns, and they pursued everything with the kind of commitment and seriousness that I would usually expect of much older dancers.

I became aware that with my work they were getting a real experiential approach, a touch-based, sensation-based knowledge of their bodies, perhaps different from their more traditional ballet or contemporary training. Our rehearsals became a ritual that began with releasing the weight into the floor, closing our eyes and using our touch to facilitate our own and each other’s release. It became obvious some days that their bodies had absorbed information overnight. Bodies connecting with information. Bodies responding and changing to new stimuli. I have never seen such rapid progress and such a whole-hearted approach to my work. I felt at various times as though I was experiencing some kind of awakening with this group of people. This was very creatively rewarding for me. Most days my contentment and excitement experienced during rehearsal spilled over into the evenings when we confidently wandered Kaohsiung inner city streets experiencing the culture. I felt happy to be there is this amazing city.

But it was the closeness that that I came to feel with the dancers and the other choreographers on the project that added such value to my experience of Taiwan. It wasn’t just the rehearsals, the night markets, the ice eating, the sight seeing, the meals or even the trips on the back of scooters that did it for me. It was the learning that we all experienced together, the sense of journey that made departing seem so unbearable. I call my four weeks in Taiwan ‘my little month of awakening’.

Elise May, a young dance artist based in Brisbane, was selected to represent Australia as part of the World Dance Alliance – Asia-Pacific program of events co-ordinated in the region. The Young Choreographers Forum is generously supported by the Jih Sun Foundation for Education in Taipei and has become an annual WDA event co-ordinated by Prof. Yunyu Wang at Taipei National University of the Arts.

2004: Amanda Phillips

In 2004, Amanda Phillips, an award-‐winning independent choreographer, director and filmmaker, created the dance work subliminal translation as a participant in the Young Choreographers Project. Her performance was part of the opening of the World Dance Alliance, Taiwan, 2004.

Closing date for applications

February each year. Application forms will be available from Ausdance National in the middle of January 2015. Potential applicants should plan to answer these questions.

- What you would gain from a professional experience such as this

- Why you would like to work in Asia

- A brief concept of your work

- A 200-word autobiography and a resume/CV

In addition to an honorarium of US$800 for WDAAP choreographers and $1,200 for WDA Americas and WDA Europe, accommodation, local transportation, dancers, studios, publicity production and office assistance are also provided; the participants fund their own travel.

Contact Ausdance National for more information.