It is in a fug of sadness that I agree, somewhat passively, to be picked up and driven the ninety minutes’ journey to St Brigid’s Church Hall in Fitzroy, Melbourne, where a weekly 5Rhythms movement meditation class is held. It’s 2012. I know nothing of 5Rhythms. Nothing of dancing, since being told you can’t dance at the age of sixteen when in training for a debutante ball in a small town in north-western Victoria’s Mallee region. Inside St Brigid’s I take off my shoes, feeling intimidated by the grace and confidence of those already moving on the floor, and wondering when they will turn down the lights. They don’t turn them down, and we are encouraged to move with our eyes open. I am thus introduced to the 5Rhythms platform in a class taught by David Juriansz that draws an average of a hundred people to move every Tuesday night. 5Rhythms founder, Gabrielle Roth, has ‘described her body of work as sacred art – rich in theater and dancing the stories of our lives, laying down our masks, unraveling by moving – not by talking’ (5Rhythms 2016, np). The practice is described as ‘a dynamic movement practice – a practice of being in your body – that ignites creativity, connection, and community’ (ibid). I keep going, every week. I rarely speak to anyone there or take part in the optional dyad or group-work exercises. I move, on my own, finding my way into a body that has become painful and distant to me. I am suffering from severe depression and when I first begin the class it is the only time I leave my home each week. I cannot even make tea for myself most days. I am an established writer and a lecturer in creative writing, but at this point I do not write, at least not with pen or keyboard. I am not sure, at this point, that I will ever call myself a writer again. Certainly, I do not think to call myself a dancer. But in the classes I move my body. Every week. I learn Roth’s rhythms, guided by the teaching and scores, and most of all through an exploration of my body and its ways of being and moving. I begin to observe this foreign, exiled territory of my body with a growing sense of déjà vu. It’s a strange thing to note – that I begin to recognise this place and range of possible movements that comprise my body, as though I have known it before – but this is my experience and perhaps it demonstrates the extent of my disembodiment and dissociation constructed over years of being immersed in depression and trauma. One of my few attachments to my body has been in the movement of it in my creative writing practices. Now, in movement, I discover a similar altered state of consciousness to that I experience in writing. The movement practice brings me into explicit relationship with my body, something that is mostly lost to me in everyday life at this time.

This essay incorporates a poetics, taking up a definition used by Laurence Louppe: ‘a study of the factors that elicit affective responses to a system of signification or expression’ (Louppe 2010, p. 4), and also addressing the ‘mission’ Louppe describes: ‘it does not only tell us what a work of art does to us, it teaches us how it is made.’ (ibid) Particularly, I explore the question posed by Louppe: ‘what path does the artist follow to reach the point where the artistic practice is available to perception, there where our consciousness can discover it and begin to resonate with it?’ (ibid) In my journey from an almost accidental blending of corporeal presence and movement with my creative writing practices to consciously perceiving and presenting my work as performance art that brings together aspects of writing and dance, I have developed two main ways of embodying my dance of the writer. The first involves a combination of live writing improvisation and simultaneous digital projection of the text that is written during the performances. This work can be seen in my collaborations with trumpet player Andrew Darling, in the Illuminous project (Darling & Perry 2017). But in this essay, I concentrate on the second way of embodying my work: the performances in which I do not overtly share the content of creative writing written during performances. I will describe a path to the availability of perception of this work, moving from the 5Rhythms movement practice that reminds me I have a body, to my first gestures towards beginning to write with pen and paper again after a period of depression, and the accidental witnesses/audiences that I attract during the development of a daily writing practice that slowly, gradually becomes a consciously framed performance art practice. Along the way, I trace reflections of my developing practice by Paul Carter and Kim Vincs and their influences on the work, and document a series of performances, from Lake Tyrell in Victoria’s Mallee region; to Federation Square in Melbourne’s central business district; to the streets where my performance practice continues today. The dance of the writer, for me, comes to embody a three-dimensionality of poetry, one that reveals to me new tools for writing and a blended practice of writing and dance. My writing and my dance become inseparable.

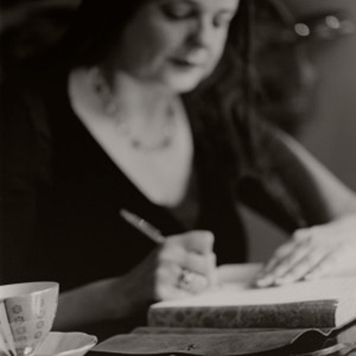

Amidst the continuing 5Rhythms movement practice, I tentatively begin to write with my pen again. It is less attached to my identity than it has been before now. I don’t think about publishing my creative writing works as poems, stories, and the like. I am not even writing works. But I write. Not at home. It is too suffocating and bleak there at this time. As well as the weekly dance sojourns on Tuesday nights, I begin to leave my flat daily and go to a café that is not too far from home on foot. I haven’t lived in the town for long. It is at the foot of a mountain, east of Melbourne, and draws many tourists. I don’t know many people here. I withdraw into deeply interior space when I go to the café and write. There is a table outside, under the shade of an awning and I can sit there in all weather. Sometimes people pause on wintery days and ask how I can bear sitting outside. I don’t notice the cold. I’m rugged up, my tea is hot, and I’m a long way inside with writing. At first, I am not quite aware that my body is here too, visible to those who walk or sit nearby. I write by hand, in my journal, using a fountain pen because I like the flowing rhythm of the ink from its nib across the pages. What I am writing has a continuous flow, uncorrected and unedited, marked with pauses in the form of dates and in the moments when I stop each day and start again the next. But it is also part of a larger flow, as life itself is in a continuous flow, marked with starts and stops according to day and night and all of a lifetime’s events and stages. I have never related well to the idea of boundaries, separations and delineations. It has not been a straightforward process to choose genres or forms for my writing – is it fiction, non-fiction, poetry, prose? Creative or academic writing? How do the edges of ‘pieces’ of writing relate to one another? My pieces are all part of a whole, and yet still ‘broken’, a perfect arrangement like when crockery breaks and falls how it will, more creatively than an artist could place the fragments.

As I turn up to dance 5Rhythms each week, I start to notice differences in my body and movements. I’m walking down a city street amidst a crowd and I begin to move through the rhythms, hearing and responding to the percussive sounds around me. I notice something similar when I am writing, but just as I go out and order tea because I still can’t make my own tea at home – there’s a whole emotional landscape between me and my kitchen – I’m not writing at home but going out to do what is perhaps my own version of ‘sacred art’ as Gabrielle Roth calls her body of work. I am observing a re-negotiation of myself and my body.

At the most intense periods of depression, I have experienced difficulty with movement. I lie in my bed on one side of my flat, looking across at the electric kettle on the bench in the kitchen area, knowing that cups, tea, and milk are nearby, and finding that I cannot will myself to sit up, stand up, cross the floor, and begin the process of making myself a cup of tea. Showering too is difficult. I will myself to get to the bathroom and turn on the taps, for hours and sometimes days before I can actually carry out the actions. And once in the shower I’m too weak to stand and must sit on the porcelain base of the shower and then stay there for as long as it takes me to will my body to stand again and turn off the taps. These recent memories are stored up in my body when I begin to write at the café. If I went back in time and documented the appearance of my body then, maybe I’d see evidence of those body memories. Louppe references Bartenieff in writing about disabled people’s movements – ‘for her, the smallest shift of weight made by a disabled person, requiring as it does the mobilisation of the whole being, is as intense, rich and moving as a dance’ (2010, p. 72). I see that my writing in the street in front of the cafe constitutes a dance right from the beginning of the practice, but it takes me years of experiencing the practice and building more deliberate intention into it, before eventually being able to call it the dance of the writer.

What I write is a pure expression of what is present for me. It’s journal-writing, sometimes known as diary-writing. A free-form inscribing of whatever streams out in the moment. I write what matters to me in the here and now.

I start to receive feedback from my accidental audiences. At first it is distracting. I do not want to be disturbed. I am even slightly irritated to discover that I am not after all invisible when deep in my writing space. An elderly woman starts to linger at my table on her daily walk and comment on the weather. I pause, look up, respond politely, and on she walks. I note that I have a regular collection of passersby who interact with me – comment on whether I must be cold or hot; mention the beauty of my journal or the wonder of my fountain pen; admire my handwriting. Sometimes I hear yearning – I used to journal: I should start that again… Are you writing a book? Am I a character in your writing? (followed by uneasy laughter). And often there are simply looks. I glance up to find someone watching me, the expression on their face raw, perhaps showing happiness, deep thought, or pain: the look quickly hidden when they notice I’m looking back at them, witnessing my witness. I do this quiet writing on the street for two years, every day, giving me time to slip in and out of reverie, observing and witnessing those who move around me in their everyday lives along the streets of the town I’ve chosen as my home. The engagement with my street-writing extends beyond the time when I am at the table. In the local supermarket, a woman says hello in a familiar way, and I hesitate, not recognising her. I see you, she says, writing in your journal at the café. Another woman introduces herself and tells me that every morning on her way to work, she drives along the main street and turns her head to check that I am there, writing at my table. When I’m there, she says, the world feels right to her and she goes on with her day. A long time after this period of writing, a woman who has become my friend confesses that when I first began writing at that table, immersed in my flow of ink and the flow from the inside, she became determined that I would be her friend and called a cheery hello to me whenever she walked by, as I went on writing.

Eventually I return to my lecturing work, and soon afterwards, after observing me writing during a long meeting, choreographer and dance academic Kim Vincs reflects to me that I write like a dancer – the movement of my hand and my pen over my pages seeming to follow a kind of micro-choreography, she says. What she has observed is not something I have designed or implemented consciously, but in retrospect it seems a pre-conscious gesture. An early embodying of what will become my dance of the writer. Around the same time, also at the university, I meet Paul Carter. Somehow he has heard about my practice of journalling in public spaces, and describes what he sees me doing in such a way that changes my viewpoint and is a significant step in my process of the embodiment of my creative practices and indeed myself. Carter reflects that in my process of writing in public spaces I sit amidst the public, in their closed bodies, each teeming inside with story, and let my raw emotions flow as I open up my own body of story, having affect on all around me and the place itself where I write.

The public do not read what I am actually writing, but my presence and my process of writing there in the open, public space of the street, have affect on those who pass by and on the street itself, adding to its perpetual layering of writing of all that happens there, all who pass by, all who are gone or on their way here. While my audience in the street does not literally read my writing, what I am writing matters. At that time of writing at the café on the street, it is a life- and sanity-preserving practice, a writing of my way back from severe illness. The affect that Paul Carter observed could not happen if what I was writing were not significant to me. What I write matters deeply to me, just as the stories inside the bodies of the audience matter deeply to them.

Carter invites me to take part in a research process one day in Melbourne’s central public space, Federation Square, where his public art work Nearamnew lies underfoot:

Commissioned by the Federation Square Public Art program, and realised in collaboration with Lab Architecture Studio, Nearamnew is an artwork designed for the plaza of Federation Square. Inscribed into the surface of the plaza, the artwork consists of three parts: a whorl pattern, nine ground figures and nine vision texts, each engraved into a ground figure. Nearamnew’s tripartite design acts as a graphic analogue of the global, regional and local levels found in a federally organised society (2016, np).

On the day we go to Federation Square in 2013, I am there as writer, accompanied by dancer Soo Yeun You, film-maker Dirk De Bruyn, and audio artist Glenn D’Cruz. The intention is that I will write in my journal, Yeun You will dance, and we will be filmed and audio-recorded by De Bruyn and D’Cruz. Yeun Yoo tells me that her improvisational dance practice is her way of journaling, but without words, via her body. Shortly before we begin, she decides she wants to dance with white paint on her face and limbs. She asks me to apply the paint and this process is spontaneously filmed by De Bruyn. It has a symbolic feel as I as the writer make marks on her with the paint. I sink into the sensuality of the movement. Making marks with body paint has a very different feel to putting ink on paper. I need to use more of my body’s weight and strength to shift the stiff, greasy paint. And I’m not making words, but marking out blocks of white, at Soo Yeun Yoo’s request. But since I am a writer, I make the non-verbal marks on her body into a kind of poetry-writing process. I picture words across her skin as I work. We move to a space intuitively chosen by the group of artists, and I sit cross-legged on part of Nearamnew.

I am particularly interested in the associations of Nearamnew with the Mallee, the region of north-western Victoria where I grew up, and the site of traumatic events during my adolescence. Specifically, there is a direct association with the pink salt lake, Lake Tyrell, that lies near the tiny town of Sea Lake, where my ex-husband grew up:

The form of Nearamnew is a global whorl pattern taken from an etching composed of braided lines folding over themselves representing water flowing between Tyrell Creek and Tyrell Lake. These lines of turbulence were created by a Boorong artist as a bark etching made near Lake Tyrell around 1860. (Rutherford 2005, np)

By the time we journal from and in our bodies in Federation Square, Soo Yeun You has already danced on the salt flats of Lake Tyrell, for the making of Opening, a 37-minute film made by Carter, De Bruyn and Yeun You:

Dancing through the film Soo Yeun You assumes the character of Red Sadie, a character penned by one of Australia's most loved poets John Shaw Neilson, with performances immersed in images from the deserted main street of the Mallee township Sea Lake at night, Lake Tyrrell, the largest lake in Victoria and Fed Square. (Media Launch 2011, np)

We journal in dance and writing for an hour in the hot sunshine. We have no score except for the sounds of people and traffic in the city.

That day in Federation Square lingers in my mind over the following months as I continue writing in front of the café near my home on the days when I am there, and as I keep participating in 5Rhythms classes at St Brigid’s hall. I realise that I have work to do, out in the region where I grew up in a town less than an hour’s drive from the edges of Lake Tyrell, the site of much trauma for me, deeply associated with the beginnings of severe depression. I make my own pilgrimage to the region and dance and write on the bed of Lake Tyrell, photographically documenting what morphs into a performance.

In January 2014, then, I return to the Mallee, which Carter describes as:

…characterised by undulating sandy plains, few surface water bodies and low elevation. It dominant flora are various species of multi-stemmed eucalypt that spring from an underground lignotuber. Mallee-like environments occur in Western Australia (Roe Botanical District) and south-eastern Australia. In the latter area – covering parts of New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria – the Mallee is interpenetrated by the Murray-Darling river system, a kind of Nile in Egypt phenomenon that baffled early explorers’ (Carter 2010, p. 10).

I go to my old school, drive past my old house, past the butchery my father once owned, and the Shire Hall where I danced at my first discos and went through the motions of debutante ball training. Thirty years have passed since I left this town, but I still can’t bring myself to enter the precise sites of pain and write my dance here in these rawest wounds of places. I drive on, to the town of Sea Lake, one hour west of where I grew up. Here it is close enough and like enough to my own trauma sites that I can do productive work but not so close that it stultifies and re-traumatises me. I camp out in the car at the edge of Lake Tyrell and wake early.

I walk across the flats, carrying an antique leather suitcase, a tripod, and my camera in its case strapped to my back. I take time setting up the camera on the tripod, planning vistas and angles. My focus is on a large branch of driftwood resting on the salt flats. As an adolescent it never occurred to me that the remains of an ancient sea were here, in the Mallee, a region that Carter calls ‘the sea-like Mallee, magnificent but marginalised’ (ibid, p. 5). Once, there was a sea: ‘The Mallee country with its uniquely evolved mallee flora corresponds roughly to the former location of an inland sea.’ (ibid, p. 23)

All the years of growing up, I had thirsted for a cool ocean to swim in and for tumultuous waves to match the restlessness inside me. Perhaps that thirst was at least partly conjured by my physical environment. Carter writes:

In the field, the Mallee may be exceptionally dry but it looks as if it could be wet – could harbour inland seas. The Mallee has an oceanic appearance, wide horizons, an undulating ground plane and ample evidence of former floods. In other words, the Mallee promotes humid imaginings: it suggests that within the visible field there may exist an inner region that is very different, that is fertile, incubating change and visions of other states. (ibid, p. 12).

The dreaming of ocean and waves may have been here all along. I put the suitcase beside the driftwood and open its heavy clasps. Inside, I’ve packed my costumes. My favourite pieces, coveted and collected, not often worn. A wide-skirted black organza tutu with a broad satin ribbon at the waist. Bright satin slips. A fake black fur vest. Red kid leather gloves. My friend and lover is here: he will press the camera’s shutter for me once I have set up the scene. There is a zoom lens because I need to be as alone as possible for this event. The costumes are layered with the agony of being a weird kid marooned in an arid place where any impulse towards the avant-garde is met with ridicule, persecution and ostracism. This day, I will wear my costumes and write and dance myself into the lingering dream of ocean in the desert.

I’ve been practising 5Rhythms for a couple of years by now, and writing at my table in public in my home town, and I’ve already done the performance with Soo Yeun You in Federation Square. I am finding my way towards my body in time and place, circling closer to closer to what I will call the dance of the writer.

My scene is ready. I walk away from him towards the suitcase and the driftwood, towards the horizon that looks just like the edge of a sea beyond the sand and the salt pans. I observe a shifting of time and place. He almost disappears, although not quite – for he is my witness and audience today and I need witnessing, just as I need the documentation of the photographs. I don’t plan to dance so much as try on the costumes and walk around and then sit down to write in my journal. But from the moment I walk away from him, it becomes a dance. I feel myself step into a deliberate space in which I am consciously performing an improvisational dance of part of my life and part of my entering and creating it in this moment.

Untitled. Photograph © Indigo Perry.

This particular dance could only have been danced by me, here and now, before this audience of one. His thin frame beside the tall tripod blends in, tree-like, with the bed of the lake. As instructed, he presses the shutter over and over. And over two hours, I move in and out of my costume pieces and in and out of nakedness. I write. I talk to myself and the air and the time and the place. I sing sounds that have no words to them. I dance. When I’m done, I walk naked to him, moving closer in the field of the photographs as he keeps on clicking the shutter. I walk out of the sounds of the wind and into consciousness of the clicking. And I’m back. The dance has come to an end. I’ve moved out of the dream field of the work. I dress, we pack up, and soon we leave for the city, both of us needing to leave the place behind.

The years I’d spent writing in public places in front of the café, coupled with the reflections by Carter and Vincs, had led me to know that my writing was part of my true art-form; my arts practice: but not all of it. Dianne Read writes of a seemingly similar realisation in a recent essay about her improcinematic dance work, and how she is: ‘playing with performing writing as something not separate from my practice but as a dance practice in itself’ (Reid 2016, p.17). I come from a place of writing being my primary practice, yet coming to understand through practice, observation and listening to the reflections of witnesses, that dance is a writing practice to me and my writing is also part of a dance practice. They are not separable.

As Louppe writes: ‘The perception of a moving body sets in motion each individual’s own imaginary possibilities and inner journeys which it would be inappropriate to try to control or even direct’ (2010,p. xxi). When I am present, live to an audience, even of only one – and regardless of whether it is an advertised performance or if it takes place unannounced (but not unintended) at a table on a public street – my writing practice cannot be broken apart from my body, there, alive, blood running inside, eyes blinking.

In discovering the presence of my body, through a combination of movement practice (5Rhythms) and journal writing in public spaces, as part of responses to depression, I gain more awareness of what I do with my body and create a poetics for it. From there comes a more deliberately framed practice, morphing from a semi-accidental performance, to a deliberate one. In this, though, is a conscious surrendering to improvisation. As Reid writes:

Improvisation is a long-term practice. Over time the capacity to attend to sensation develops, deepens, and over time the body reconfigures itself and its sensations. It is necessary to practice it rigorously and repeatedly, returning to the investigation anew despite the findings of yesterday. The knowledge of the body changes experientially, it is, like the physical body, not inert but alive and changing’ (2016, pp. 21-2).

Over time – years – I begin to feel in to my street-writing as a performative practice, noting its subtle differences with every day. I notice that I have practised the same set of rituals around my street-writing for years. I sit down – I’ve stopped even having to order: the staff see me approaching and begin to prepare my tea – and take my journal from my bag, the pen tucked inside the pages as a kind of bookmark, and lay it on the table, closed. My tea arrives. English Breakfast. I take the little milk jug from inside the cup and place it on the table. When the tea has brewed a few moments, I pour milk into the cup, place the strainer over the top, and slowly pour in the tea. I pick up the spoon from the saucer, and stir, gently, without touching the bottom, to disperse the milk in a cloudy swirl that reminds me of my process of sinking inwards to what I will write. (Once I knew someone who stirred his tea with a graceful motion of the wrist, and when I commented on it, he said, Some people stir tea like they are trying to beat it up. I think of that, and soften my own stirring.) I sip, elbows resting on the table, holding the cup aloft. Sometimes I think of my paternal grandfather when I do that, for he too held his cup in this way and gazed dreamily over the top through the steam. And I open my journal to write. I write for at least an hour at a time, often two or three, pausing periodically to order more tea. When the flow of writing comes to a still place, I order a last pot of tea and finish as I began, gazing over my teacup’s rim and letting it all settle.

By now I am developing my other works involving live improvisation and projected writing, but my journalling-dance in the streets continues to be one that is spontaneous, unannounced, and is for an accidental audience. That first café closed down long ago, and so I move between various cafes. Photographer Kate J. Baker observes me and asks to photograph me. On the day, she asks me to ignore her and do what I usually do, and she documents my practice.

‘Indigo’s Journal’, photograph ©Kate Baker http://www.lumennaturae.com.au

I have postcards of the image printed, and begin to leave the cards on tables, explaining that I have been here, writing, directing people to my website if they want to know more about my practice. And thus, my street-writing practice quietly becomes consciously performative. I am not on a stage. The performances are not advertised, apart from on the postcards. But it is my dance of writing.

Many of my movements are subtle, even tiny. In the beginning, to pick up on Louppe’s work, I have no aim or intention to be expressive in my movement. And yet the movement is expressive: ‘All movement is automatically expressive even if it does not have expression as its aim.’ (2016, pp. 4-5) Mostly the dance is of my pen across the page, as Kim Vincs noted. There is movement of my head, too, and my shoulders, micro-movements travelling all over my body, and my facial expressions are very changeable when writing – very open, emotionally. I have long hair that I touch with my left hand often when I write. There is a periodic getting up and stretching and walking to the bathroom, still immersed in my interior writing space. It is not unlike walking through a dream. Louppe notes that contemporary dance has moved focus away from the primacy of the torso as a focus of movement, to other parts of the anatomy, explaining that the head, for example, could be ‘body, weight, matter’, or become ‘dislocated like an appendage almost to become detached from the body’, or ‘a character: it can become a body…’ (ibid, p. 41)

As I become more consciously aware of what I am doing in my creative practices, I note the poetry of the body as well as the poetry in language. Louppe writes:

…we can understand how an art such as dance which, like poetry in language, tends to develop activity in the affective movement factors, is, more than in verbal poetics, connected to all of the deepest roots of the individual and that these are able to ‘colour’ a gesture (enonce gestuel). Dance, which can be considered the body’s poetry, intensifies and exemplifies this connection. Here, more than elsewhere, the double presence, dance-spectator – also a corporeal encounter – actualises itself in an intensified dialogue. This dialogue is even more able to awaken aesthesias because it takes place as an encounter in time and space (ibid, p. 5).

In my street-writing work, I find that my poetry in language is given a further level of expression when I explicitly combine it with the body’s poetry. And in not sharing the content of my writing during performances, I am playing with another dimension: expressibility, and more pertinently, inexpressibility in language – as theorised by Julia Kristeva, who:

…finds in acts of artistic expression that press language to its limits – that is, in the ruins of the symbolic – a zone, by definition incommunicable, in which desire bursts forth (Eliot 2004, p. 83).

Eliot goes on to ask:

Is this zone a set of organized meanings, a language, or is it pre-linguistic, and hence indescribable? Not so much pre-linguistic, according to Kristeva, as an expression of the pro-linguistic: affects, bodily dispositions, silences, rhythms’ (ibid p.83).

And I note the circling back to rhythms and to the body on the path I’m tracing.

The corporeal presence has its own poetry – according to Louppe the body’s poetry is dance. The act of writing too has its own poetry – not just words but a gesturing and reaching away from words into space, into dream, vision, and what is sensed and desired but not necessarily made explicit in words. And the constant separation between language and meaning, and gesture towards expression forever falling into an abyss of impossibility of expressing what the writer most hungers to express, is exacerbated and layered again and again like flesh in a dance – the dance of the writer. This is why I continue my street-writing today: it has different purposes and perhaps mysteries to the writing practices that involve sharing my writing’s content explicitly with my audience.

Through poetic language, I gesture towards expressing the inexpressible. But in my embodied practice of writing, with an awareness of the presence of my body in my making of writing, I observe a greater sense of power in expression. What is taking place shifts beyond the two-dimensional page of writing. The presence of my writerly body is not separable from the words I write. The practice that I find myself inhabiting is one in which the corporeal presence of my body is not one I want to separate from the body of my writing. I have shifted from writer to writer-performance-artist, and perhaps most aptly, writer-dancer, with Louppe’s beginning to a chapter entitled ‘The Poetic Body’, coming to mind:

To be a dancer is to choose the body and its movement as one’s relational field, as one’s instrument of knowledge, thought and expression. It is also to trust in the “lyric” character of the inorganic, without at the same time ascribing to a precise aesthetic or form; neutral movements or body states (expressly unaccented and without “design”) have their own lyrical quality as much as any overtly spatialised and musicalised movement. The main thing is to work first of all on the organic conditions of this poetic emergence. Once this fertile choice is made the body becomes a formidable tool of consciousness and expression (ibid p. 38).

And so, today, I am writing in the streets again, outside a café in the late winter, with soft rain falling, the clouds an inky, shifting body not unlike an intermittent lake in the sky. I dance and write in a sensual dialogue.

References

- Carter, P 2010, GroundTruthing: Explorations in a Creative Region, UWA Publishing, Crawley.

- Darling, A & Perry, I 2017, ‘Illuminous’, Illuminous Project, Melbourne, accessed 12 June 2017. http://www.indigoperry.com/illuminous

- Eliot, A 2004, Social Theory Since Freud: Traversing Social Imaginaries, Routledge, London & New York.

- 5Rhythms 2016, ‘Gabrielle Roth’s 5Rhythms’, 5Rhythms International, New York. Accessed 24 August 2016. http://www.5rhythms.com/gabrielle-roths-5rhythms/

- Louppe, L 2010, Poetics of Contemporary Dance. Translated by Sally Gardner, Dance Books, Alton.

- Material Thinking 2016, Nearamnew, Material Thinking, Melbourne, accessed 24 August 2016, http://www.materialthinking.com.au/portfolio/nearamnew/

- Media Launch 2001, ‘Fed Square Story Telling Turns Another Page’, Media Launch, Melbourne, accessed 24 August 2016, http://medialaunch.com.au/media-releases/1-latest-news/303-fed-square-story-telling-turns-another-page

- Reid, D 2016, ‘Improcinemaniac’, Brolga 40, 16-29.

- Rutherford, J 2005, ‘Writing the Square: Paul Carter’s Nearamnew and the Art of Federation, Portal, vol. 2, no. 2, July 2005 1-14.