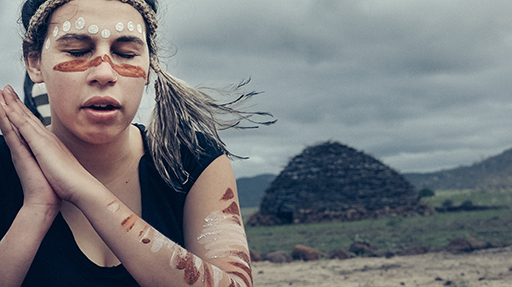

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.‘Where do you feel so at home you could dance likes no-one’s watching?’

This was a question to provoke participants’ imaginations and aid their choices in a project called Dancing Place in Wyndham, Victoria in 2016. Although the project was informed by complex sociological issues, its parameters were simple: residents were invited to choose their favourite place in Wyndham, their favourite music, and dance in that place, to that music, for video. Yet reflecting upon what transpired, the complexity returns: there is a lot going on at this nexus of place, body, identity, film (video), movement and representation.

This paper collates some thoughts about the phenomenon of dancing in relation to place, and issues of visibility and marginalised people, as represented in the video series. From my vantage as facilitator/ director of the Dancing Place project, I anticipate some insights from this engagement experience may be worthy of sharing with dance and performance practitioners and scholars, and suggest that dance offers unique potential to community development and place-making projects. I propose that an aspect of what transpired in the project could be described as a phenomenology of belonging. The participants’ danced involvement with the sites, combined with the making visible of diverse people performing an aspect of their identities, collectively generated a representation of co-presence in place.

The Project

Wyndham is a local government area west of Melbourne, which has reported stigma connected to ‘postcode discrimination’ (Warr et al 2010), is expanding rapidly in population and building sprawl, and is highly culturally diverse. As part of a sociological research project addressing stigma, I identified and sought out residents from across Wyndham that might have limited capacity to participate in social and cultural activities for reasons of social isolation or other particular issues of marginalisation, in addition to putting out an open call for participation. With this ‘pro-social’ ethos (see Atkinson, McKenzie & Winlow 2017), I visited in person many groups and individuals to invite their participation and accommodate their specific needs, in consultation with council staff and local community services. I also steered the project with the artistic outcome in mind, to represent a broad spectrum of people in terms of age, cultural and geographic diversity (across the quite vast and varied area of Wyndham), to curate an eclectic mix of music, dance genres and spatial locations. This balance between the aesthetic and social outcomes permeated the entire project; indeed, these two aspects are so intermingled in such a project that they could be considered as one. In theatre facilitator Myf Powell’s words, Dancing Place embraces an ‘inclusive aesthetic’ (2010, p.198), or perhaps an inclusive or social kinaesthetic, as proposed by Randy Martin (Lepecki 2004, p. 48).

Screendance artist Dianne Reid shot and edited nine videos featuring over seventy residents dancing in their chosen sites, from domestic spaces within their homes, to public outdoor spaces, natural environments and shopping malls. As appropriate, drawing upon my experience of site-responsive performance making, I offered direction to the participants to spatialize their dance in relation to the sites. The final Dancing Place series comprised: youth breakdancing on a basketball court; traditional Indian and Bollywood moves around a ‘hills hoist’ clothesline; a seniors group line-dancing beside a creek; a Body Weather exploration by the river; Aboriginal creation stories danced at a sacred site; salsa in a boat shed; a Lisu hill tribe (China/ Myanmar) folkdance at Werribee Mansion; a rendition of Blues Brothers’ ‘Shake a Tail Feather’ in a shopping centre; and a senior school student grooving with a box on his head (apparently in reference to ‘Minecraft’) in a park.

The videos were intended to be presented as an exhibition of concurrent, looped screen works across three or four projections and/or screens. Dancing Place aimed to represent in parallel multiple cultural and social identities, experiences and traditions as expressed through the different dance styles according to participants’ choice. By inviting participants to choose the place they felt most 'at home', the project bridged public and private spaces, from kitchen to the beach. The videos highlighted the commonality of enjoyment of dance (in many guises), music and local places across generational and cultural divides, as well as varied socioeconomic circumstances. To most participants, the invitation to choose a song or piece of music implicitly determined the style of dance they would perform to that music. By virtue of being the participants’ ‘favourite’ songs, the dance genre was also very familiar to them, thus the participants could inhabit their dance with enjoyment and ease. Dancing in a familiar mode and place was thereby a way of eliciting participants’ non-verbal articulation of self-selected aspects of their identities. The combination of these two decisions: of location and content (music/dance) facilitated a creative expression of locational identity. Each video felt like a world unto itself, specific to the participant/s.

Viewed as a collection, the nine videos connoted a shared place inhabited and enjoyed creatively and multifariously by a broad range of people. Our previous arts initiatives as part of the Challenging Stigma research in partnership with local council, City of Wyndham, had focused on exploring social perceptions and building place identity within particular neighbourhoods. Dancing Place was funded by the council through an ‘Inclusion, Identity and Connection’ grant and was the final artistic outcome of my 14-month (one-day-a-week) residency. From a community cultural development perspective, Dancing Place aimed to connect communities across Wyndham, contributing to the development of a sense of identity for the City as a whole—as a culturally diverse City where people create their different senses of home and ‘belonging’ side by side. Whilst a sense of co-presence (or parallel belonging) in place is evoked in the viewing of the video collection, the inter-relation between different groups of residents will be actualised at the exhibition at Wyndham Cultural Centre in late 2017, when we plan to bring together many of the participants and their respective communities for the opening.

I propose that the form of dance film offers a particular kind of belonging to this place-making context: a relationship with place that is sensory, embodied and multi-dimensional.

Sensory interstices: dance, place and film

The project aimed to visualise relationships between people and place, thus the use of video was not simply a documentation of the dance, with the place incidentally in the background. Dancers merge with the space around them as they dance, gradually entwining themselves (the foregrounded subject) with the ‘background’, or drawing the background closer into the foreground through the intricate lines created via movement. In any performative space where we are liberated from a specified ‘front’ (as epitomised by the proscenium arch stage), the possibilities to experience a fluid spatial orientation expand. Indeed, the medium of video or film obliterates spatial confines such as front/back, as articulated by writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag: ‘…cinema (through editing) has access to an illogical or discontinuous use of space’ that is an ‘emancipation from the ‘frontality’ of theatrical models’ (Reid 2001, p. 8 citing Sontag 1966, p. 367). This opening out of spatial perception afforded by film in some ways exacerbates the opportunity for audiences to engage with place or location of the film multi-sensorially, albeit through a visual medium. Film theorist Ross Gibson in his essay ‘Enchanted Country’, claims that the cinematic moving image is a medium by which the viewing subject can be ‘stitch[ed] in’ to the landscape:

Film […] folds a spectator into the scene through the all-encompassing environment of sound and through editing sequences which lay out a space over and around a viewer, who is being ‘shifted’ constantly in vantage point to a profusion of possible sites-of-being and sites-of-seeing. […] the place of the film enters the spectator’s mind and soul. (1993, p. 475)

Dance film has the potential to take the immersive experience of viewing film described by Gibson even further than other genres, to engage the viewer’s senses of kinaesthesia and touch in a rich phenomenological interplay, which brings the viewer into intimate proximity with both the visceral dancing body (Reid provokes: ‘to make my sweat bead on the surface of the screen’ (2001, p. 2)) and the features and atmosphere of the place/ location. It enables the viewer to be drawn into the place in a way that is closer to the experience of the dancer than the perspective of an audience member in the situation of a live performance, whereby the performance is viewed necessarily at a distance. Dancing Place videographer Dianne Reid is both a theorist and practitioner of dance film or ‘screendance’, whose practice is keenly immersive and kinaesthetic. She often filmed whilst running along with and weaving through the dancers with the camera, almost dancing with them. In her thesis Dance Interrogations, Reid reflects: ‘As I film the dance from within, moving alongside and in relationship to the dancer, I feel I enter my own dance of “viewing-with”’ (2017, p. 56). Thus, the view we get as audience of the dance and the site is often a mobile one, which reflects the experiential perspective of the dancers as they move through and in relation to the sites. The camera brings the viewer into closer range with the surfaces and textures that the dancer is engaging with, and follows the dancer’s point of view, movement and rhythm.

I had met previously with some of the participants and rehearsed their dance at the site, with their chosen music. I had discussed with them their rationale for choosing this place, what was significant about their relationship to it, then given directions or suggestions as to how they might highlight, activate or relate to surrounding features to corporeally represent their connection to the place. Other shoots were much more spontaneous, depending on participants’ availability and enthusiasm to rehearse prior. In some cases, Dianne and I would simply meet the participant at the site, play the music and roll the camera, and I would attempt to direct the action in the moment according to the conditions, such as weather, participants’ impulses, geographic features and incidental occurrences at the site.

I asked Dianne to capture the Country/place/site in equal degree to the performers: to treat the site as if it were also the ‘talent’ (to borrow commercial film jargon). After we had shot a few of the videos, I realised one of my interests lay in the literal, interstitial space between the dancer and the place. I observed the participants/performers’ interactions with the places, which evoked a mutual, if ephemeral, inscription of place upon body and body upon place: grass stains on the edges of white skirts, footprints on damp grass, a dapple of rain upon skin and hair, crackling of leaves and sticks as the body’s weight leaned into them, skin surfaces scratched and, reciprocally, prickles and twigs attached to clothing, arc-shaped marks upon the dirt path, mud encrusted boots, etc. I have explored and considered this reciprocal engagement extensively in my own site-responsive dance practice, in which I intentionally improvise with place (Locating: Place and the Moving Body, 2009). However, now I observed something similar, if less conscious and pronounced, occurring in the corporeal inter-relating between these community members’ bodies and the sites. Whether the dancers were conscious of these interstitial effects as they danced or not, the reciprocity of sensory impressions generated relationality between body and place.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.Evolving relationships between self/body and place

Indeed, there is always, already relationality between body and place. In ‘Between Geography and Philosophy’, Ed Casey proclaims there is (now) ‘no place without self and no self without place’; that each is essential to the being of the other in a relationship of ‘constitutive coingredience’ (2001, p. 684). Having traced historical philosophical thought on the relationship between place and self, Casey defined place in terms of its relationship to humans: ‘an immediate environment of my lived body—an arena of action that is at once physical and historical, social and cultural’ (p. 683). This seems too anthropocentric in my view, implying that places need humans in order to exist, but Jeff Malpas extends this beyond the human to the idea of place as ‘a particular locale or as that ‘within which’ someone or something resides’ (1999, p. 22 emphasis added). Casey largely credits phenomenology, as an attempt to give a ‘direct description of first-person experience’ (683), for contesting earlier dichotomies that held self apart from body (in the well-trammelled Cartesian divide of mind and matter), and self apart from place (established by Locke, who, in the eighteenth century, considered place as merely a parameter that lacks consciousness) (Casey, pp. 683-4). As phenomenologists and contemporary philosophers, such as Elizabeth Grosz (1994), have convincingly established, the body is now recognised as integral to selfhood, with no neat distinction between personal and physical identity, and place is regarded as constitutive to one’s sense of self (Casey, p. 684).

Notions which describe the enacting of relationship between self and place include Heidegger’s articulation of utilitarian actions of work, Werkwelt, whereby ‘what we create in the work-place helps us to grasp the particular place we are in as the particular person we are’ (1962)), and Bourdieu’s notion of habitus (1977), which Casey proposes as the ‘mediatrix’ between ‘lived place and the geographical self’ (p. 686). Casey also explores Sack’s notion that ‘places have become thinned out and merge with space’ through processes of ‘glocalisation’, whereby this locale is linked to every other place in global space via the Internet (p. 684). This contributes to the ‘less densely enmeshed relationships of self and place through work’ and the ‘thinning’ of the habitus linking places and selves (p. 686). Casey does not mention the (in many cases, painful, desperate) departure of people from places of ancestry through diasporic processes proliferated by disaster, persecution and war, which characterise global human movement of our time. Geographer Linda McDowell notes that the extensive movement of peoples from their places of birth and ancestry, through imperialism, immigration, refuge and simply through travel, has created a globalised sense of place, changing the notion of place as ‘authentic’ and ‘rooted in tradition.’ According to McDowell, place has come to be defined by the intersection of particular socio-spatial relations that create a place’s distinguishing qualities (1999, p. 4). She observes:

...the commonsense geographical notion of a place as a set of coordinates on a map that fix a defined and bounded piece of territory has been challenged... [and now] places are contested, fluid and uncertain. It is socio-spatial practices that define places and these practices result in overlapping and intersecting places with multiple and changing boundaries… (1999, pp. 4-5)

The new authenticity of place McDowell describes is ‘made up from flows and movements, from intersecting social relations rather than stability and rootedness’ (p. 5). That place is characterised by greater fluidity and instability now than in the past represents a major shift in the organisation of people’s lives and as such is the impetus for the sizeable body of work being produced across a broad range of fields of knowledge on the subject of place. These departures from deeply enmeshed relationships with place are literally disorientating: leaning towards both loss of place and loss of sense of self. In response to the alienation and potential social division caused by these shifts away from our earlier, presumed connections with place, a significant conscious reinvestment in place is under way in many spheres of activity, including at the level of neighbourhood via local councils and community cultural development projects.

If our experiences of habitus are ‘thinning’, causing evaporation of both place and self, perhaps a re-focus to the ‘thickness’ of seminal phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notion of ‘flesh’ as connective sensorial communication is timely. Merleau-Ponty described the intersubjective relationship between humans and the non-human world, considering that we are tangibly connected to ‘the things’ or the features of the exterior physical world through our senses, by the ‘thickness of the look and of the body’ (1968, p. 135). The body’s ability to see and sensorially perceive the world around it is our means of relating to it and this relationship—the communication that Merleau-Ponty calls ‘flesh’—is what links us to place:

The thickness of the body, far from rivalling that of the world, is on the contrary the sole means I have to go unto the heart of things, by making myself a world and by making them flesh... It is the body and it alone, because it is a two-dimensional being, that can bring us to the things themselves... (1968, pp. 135-6)

If the dancer is conscious of these sensory effects of, and connections with, their surrounding environment, these can become the ‘material’ for the dance itself. The Body Weather dancer (a professional performer), in her improvised exploration by Werribee River, utilised subtle multi-sensory listening to the specificities of that place (and her finely tuned perception of those inputs) to inform the embodied qualities and movements she performed. In the Indigenous dancers’ case, the dance was primarily a ritual enacting relationship to Country, taking stories about features of this place, such as animals or plants, as its choreographic impetus (as I understood from conversations with Wangal United cultural leaders, 2016 and similarly reflected in other Aboriginal dances I have witnessed and researched (Taylor, 2012)).

However most dance styles which emphasise spectacle and/or social participation do not attend so deliberately or closely to these affects by place. The Lisu dancers’ traditional folk dance consisted of choreographed, pre-learned spatial patterns, steps and movement sequences, performed in relation to the other dancers in the group, all executing the same movements simultaneously (although there were often different parts for the men and women). As far as my untrained eye (in viewing this form of dance) could perceive, there were no improvised movements, nor any apparent foci upon the influence of the surrounding features or atmosphere to inform the dance. The dancers were nonetheless consciously or unconsciously responding to ‘place effects’ through subtle adjustments, such as differing the degree of flexion in their ankles to absorb the impact of jumps upon landing on the tiled veranda of the Werribee Mansion, in contrast to jumping (in their previous scene) on the soft grass of the lawn. Beyond that which was perceptible in the bodies of the dancers, there were superficial traces, such as the damp green grass leaving stains on the hems of the women’s skirts and temporarily flattened trails upon the grass where the dancers’ trajectories had impressed it. But more than that, the dancers merging with the background as they dance, activating the air around them, pushing into and drawing impetus out of the ground, was an interaction with and involvement in a place which ephemerally exuded, inscribed or wove the self-body into the place, creating an atmosphere that was a combination of their (cultural) dancing presence and the existing place.

I propose that dancing in a place in these ways develops a kind of phenomenological belonging. If to ‘belong’ means to fit in or be related to a place, dancing in a place can be a literal process of physicalising belonging. Community groups of non-professional dancers may not consciously have this intention (and probably none of the participants in this project except for the Body Weather dancer would have heard of site-specific dance), but nonetheless they became involved in the place via dancing in it: they impacted the place and it impacted upon them; they were actively present in the place. This involvement, I propose, enhanced their ‘belonging’ to the place. They were at once expressing locatedness, declaring presence and in a process of further locating—or thickening their experience of habitus.

Embodying identity—claiming space

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.Notwithstanding the complex theoretical elucidations of the dancing body’s presence (Lepecki, 2004), I wish to explore how the active becoming-present and representation via video of dancing bodies holds potential sociologically. Whilst the Wyndham residents’ participation was at times joyous, passionate, sensitive, skilful and communal, the visibility to the broader community (in the public domain during the video shoots, in the art environment of the gallery, as well as further afield via online formats) of marginalised groups dancing in their favourite places, was also profoundly political. For many residents of low-income neighbourhoods, an opportunity to be seen expressing themselves creatively was rare. The seniors group and basketball youth, at their divergent ends of the age scale, were both seemingly surprised to be invited to participate. Each group had a similar response, to the tune of: ‘But who would be interested to see what we do?’, whilst they were also obviously pleased to be invited. To be viewed exuberantly taking up public space, in sites deemed to be places to be avoided, instead of complying with social norms or the behaviour one expects to witness by these age groups, takes on a more radical stance.

Our interviews about social perceptions with residents of one of the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Wyndham revealed that some residents thought they were perceived as ‘scum’ because of where they lived (‘En route to Heathdale’ project, 2015). Zoe Morrison, researcher for charity organisation Brotherhood of St Laurence, advocates for a ‘politics of recognition’ as part of contemporary debates about social inclusion (2010). Morrison argues for the need to expand the views of injustice as economically focused and take into account that ‘due recognition is not just a courtesy, but a vital human need’ (Morrison 2010, p. 10, citing Charles Taylor, 1994). Morrison notes that:

…non-recognition or misrecognition is a form of oppression because it imprisons someone in a false, distorted or reduced mode of being. People who belong to stigmatised groups in society, and who experience that stigmatisation repeatedly, internalise negative self-images. (Morrison 2010, p. 10)

Conceived as a strategy to address negative place-based recognition and portray more nuanced images of people and places than the stereotypes imposed by outsiders (and internalised by residents), Dancing Place offered residents opportunities to contest these representations by creating their own.

Passers-by at the Point Cook shopping centre smiled, photographed and stopped to watch the filming of a mother and her daughters as they performed ‘swimming’ arm movements to each other on moving escalators and shook their ‘booty’ traversing supermarket aisles to the soundtrack of Ray Charles’ ‘Shake Your Tail Feather’. The anomaly of the dancing activity in contrast to the usual pedestrian practices of consumers at these sites invoked humour and play. This little family infused their familiar environment with their cheeky attitude as their way of ‘owning it’, or claiming belonging.

The videos in the Dancing Place series raised the question: Who am I to be [dancing] here? Seeking belonging as they enacted it; the dancing participants were at once aspiring to become present, and claiming their presence-already in place. Dancing in a place could be construed as a physiological grappling with identity. From the perspective of the dancer/s, dancing in a place for video visualises what they wish to represent of themselves in relation to their chosen place/space/site. Each self/body located (dancing) in a place is sexed, gendered, has its own mix of ancestries, its own unique set of memories, experiences, abilities, etc., as well as its own relationship to the specific place, whether that be a longstanding relationship or a very recent one.

The adjunct of this project’s parameters—to bring one’s favourite music into a place—strongly permeated the atmosphere and was potentially mnemonic or evocative of another place, culture or subculture. It also activated the site, announcing the presence of the player/s of the music, and suggesting an event.

For cultural groups, such as the Lisu people from Myanmar and China, the collective experience of dancing together to music from their homelands, vitally exacerbated an effect of bringing that place to this place. We bring our identities corporeally embedded within us, and these identities take on a shifted relief with a new background. Individually it can be overwhelming being in surrounds where everything is new (let alone the struggles to find work, operate in a foreign language, bear the brunt of racism, etc.), so coming together as a group and dancing a dance that expresses one’s cultural heritage located consciously in the new place was an act of affirmation for the dancers, of simultaneously becoming present and asserting presence.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.Art historian Miwon Kwon in One Place after Another charted shifts in site-based art practices, which reflected the changing conditions of place in the contemporary world, to encompass a notion of site as an ‘intertextually coordinated, multiply located, discursive field of operation’, rather than the rooted, geographically-bound identities of the past (2002, p. 159). Kwon suggests finding a terrain between this trend of deterritorialised mobilisation and the more traditional, grounded site-specificity and imagines a new model of ‘belonging-in-transience’ (p. 166). A clue to this model, Kwon indicates, might be in considering the range of seeming contradictions together, to inhabit them at once and find a sense of belonging with the instabilities: ‘to understand seeming oppositions as sustaining relations’ (p. 166).

Dance is a form that can straddle these contradictions, indeed embody Kwon’s idea of belonging-in-transience, by relating to the present moment in place and simultaneously referring to and viscerally recalling (through cultural choreographies) other places from whence the dancers, dance and/or music has come. For the Lisu group, who were so persecuted in their own country that they were prohibited to engage in their cultural activities, performing and recording the dance is especially significant: it is perpetuating a cultural form which is at risk of being ‘lost to the world’—on the steps of a colonial house in Wyndham, Australia.

For the young dancers from Wangal United Aboriginal Corporation, performing dance and song at sacred site Wurdi Youang was a conscious ritual to embody their ancestral identities and affirm their continuing cultural connections to Country. The intergenerational psycho-physical trauma that has fractured families and communities of Indigenous Australians since colonisation has still not been properly acknowledged in the official national narrative. Reflecting on this ruptured past which impinges upon the present, a mother and organiser of Wangal United who was interviewed for the video (which morphs between dance film and documentary), recalls:

Protecting my younger sister meant that I needed to … provide for and protect my family, and in between that my sacrifice was that I wasn’t able to connect to Country [through participation in cultural education]. So I’m so proud that my daughter now has the opportunity to do that [by learning about culture including dance through Wangal United]. And she’s learning such amazing things! And I’m learning amazing things through that. (Wangal United group video interview 18/6/2016)

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.

Still image from video by Dianne Reid, Dancing Place series, Wyndham, Victoria, 2016.Other Wangal United dancers and family members at the film shoot at Wurdi Youang also reflected upon the young people’s pride in their cultural heritage through dancing at this site, which they inferred enhanced their individual and collective wellbeing through their embodied expression of identity, which is intrinsically related to place. That family members only a generation prior, were denied these kinds of opportunities (for many reasons, but most traced to legacies of colonisation), gives political and sociological salience to the act of performing cultural dances on Country for these First Nations youth.

In ‘The Black Beat Made Visible: Hip Hop Dance and Body Power’, Thomas F DeFrantz analyses how African-American social dance ‘constantly reconstitutes narratives of identity and politics by choreographing the body’s expressivity within the crevices of hegemonic racist systems. Here presence assumes its non-metaphysical aspect: it is synonymous with a will for power...’ (Lepecki 2004, p. 7) It is this kind of politically charged presence I am gesturing towards here, although the Wyndham residents would not be so avaricious as to express a ‘will for power’ but rather, and merely, a sharing of space. In Dancing Place the participants are not necessarily or consciously resistant to power dynamics, but in some cases the (cultural) groups’ visibility in these locations is relatively new, and, in a larger context of issues of diversity, multiculturalism, refugees and immigration policy, it is contested.

Considering methods to ethically facilitate diverse cultural performances, I reflected upon other examples of performing place with community members. Renowned Australian performance artist Jill Orr invited Indigenous groups and other local community groups as well as performers from various immigrant cultures to contribute to her place-based performance The Crossing (Mildura, 2007) and video installation From the Sea (Warrnambool, 2003). The Indigenous groups in particular were encouraged ‘to perform their own dances, chosen by them, in their own terms, in their own place’ (Taylor- Orr interview, 2009). Orr deduced that this was the best way to acknowledge Indigenous history and contemporary Indigenous presence without reiterating colonising paradigms by ‘telling them what to do or by anyone else attempting to tell their story for them’ (Orr 2009). In this way, Orr invites Aboriginal and other cultural groups to represent themselves, whilst understanding that their contribution forms part of a larger work. As a performance maker/ director she believes she cannot represent others’ perspectives; she can only create the space for them to represent themselves. The open-ended parameters for Dancing Place similarly set up a framework within which participants could represent themselves. As facilitator/ director of the project I had a sense of the overall effect of the collection of videos: that it would be multiple and varied in terms of representation as well as aesthetic. How participants chose to fill these frames was up to them.

Dancing Place embraces an ‘inclusive aesthetic’ as articulated by Melbourne theatre maker Myf Powell as riposte to the tensions between ‘excellence’ and ‘access’ debated over the last decade with the increasing prominence of socially-engaged arts practice (see Holden 2008, correspondence between Kester and Bishop 2006, Kester 2011, and Bishop 2012). Powell advocates for an aesthetic, such as inclusive theatre (all abilities, all ages), that ‘feels truthful, almost painfully real’ by its more accurate reflection of the spectrum of human existence (Powell 2010, p. 198), and argues that, far from the oft-inferred compromise of quality, the site where art meets ‘real life’ has historically been the site of the avant-garde (pp. 204–5). Many performance and dance projects of recent years have attested Powell’s proposition that this nexus with community is indeed a productive stimulus for the art (see also Warr, Taylor & Jacobs, ‘You can’t eat art’ for further critique of these developments). Randy Martin refers to a ‘social kinesthetic’, whereby there is a ‘sentient apprehension of movement and a sense of possibility as to where motion can lead us, that amounts to a material amalgamation of thinking and doing as world-making activity’ (in Lepecki (ed.), 2004, 48). An inclusive or social kinaesthetic might be construed in the commonality of corporeal enjoyment that is evident across the vastly divergent dances performed by participants of Dancing Place, and empathetically felt by its viewers via Reid’s immersive mode of filming.

Towards co-presence

In a review of Peter Read’s Haunted Earth, Emily Potter observes that Read’s comparison of Indigenous and non-Indigenous presence in place is laden with the anxiety that non-Indigenous Australians ‘live thinly on the land’, which she proffers is itself unproductive. She suggests that,

It is perhaps by looking beyond depth as the site of affective meaning and towards the tremors and vibrations of the earth’s surface that fear can be replaced by hope. For here, in the irreducible tactile, aural and visual encounters that occur between self and other, the future opens up. (2005:125)

In inviting the diverse peoples of Wyndham to engage with local sites through dance, the video series valued this close-range encounter with place as common ground: a kind of phenomenological equity. Dancing in non-dance spaces is unavoidably sensory and immersed, whether the participant’s relationship with this area goes back for generations (even millennia) or just a matter of weeks. Knowledge of place of course differs and expands with time and the Indigenous experience is profound, deep and special, hence Wangal United’s video for the Dancing Place installation was presented on its own continuous loop on its own screen/ projection, whilst the other videos rotated on other screens. But in the moment of encounter we all perceive place through our senses and our differing experiences of this phenomenological relationality transcend assumptions, judgement and stigmatisation. Place is a leveller: it is literally common ground, hence my advocacy for further explorations of site-responsive art in community cultural development contexts.

Perhaps the point of any endeavour to engage community members in arts projects could be subsumed under a broad aim of creative participation that facilitates learning to live in better co-existence with each other and our environments. In a place that is experiencing rapid change such as Wyndham, it would not have been accurate to depict these groups and individuals together as a unified ‘community’. The nine videos of Dancing Place exhibited in parallel connoted a shared place, embodied, inhabited and enjoyed creatively by a broad range of people in all their multifarious styles, side by side. Dancing brought each participant’s body, embedded with its unique combination of experiences, into communication with place in an ephemeral articulation of identity. The collective impression gave value to many ways of being (living/dancing) in relation to this place by diverse people. Whilst the video outcomes were light-hearted—often joyous—they also engendered a claiming of presence in place, which was significant sociologically through positive recognition by the broader community, as well as having political potency in the context of debates about immigration policy and evolving acknowledgement of First Nations’ culture, knowledge and presence. Through the immersive visual experience of screendance, audiences were enticed to expand their perceptions of this area to encompass manifold relationships to place. The multiple moving images, drawing the viewers into the action and place through their senses of kinaesthesia, generated nuanced perspectives, which interrogated stereotypes and evoked an optimistic sense of co-presence.

Dancing Place was an artistic outcome of an ARC Discovery Project entitled ‘Challenging the stigmatisation of poverty and place-based disadvantage’ led by sociologist Deborah Warr at University of Melbourne. Dancing Place premiered at George Paton Gallery as part of Not THAT Place: Art versus Stigma exhibition (December 2016), and was a major exhibition at Wyndham Cultural Centre in late 2017.

References

- Atkinson, R, McKenzie, L, & Winlow, S (eds.) 2017, Building better societies: Promoting social justice in a world falling apart, Policy Press, Bristol. (especially Warr, D, Taylor, G & Williams, R, ‘Artfully thinking the prosocial’, pp. 81-94)

- Bainbridge Cohen B, 1993, Sensing, feeling and action, Contact Editions

- Bishop C, 2006, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’, Artforum, pp. 179-185

- Bishop C, 2012, Artificial Hells: Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship, Verso, London, New York.

- Bourdieu P, 1977, Outline of a theory of practice, trans. N.M Paul & W.S Palmer, Zone, New York.

- Casey E, 2001, ‘Between Geography and Philosophy: What does it mean to be in the Place-World?’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 91 (4), pp. 683-693

- DeFrantz T. F, 2004, ‘The Black Beat Made Visible’, in Lepecki A, Of the presence of the body, pp. 64-81

- Gibson R, ‘Enchanted Country’, in World Literature Today, Summer 1993, p. 475, cited in Muecke S, 2004, Ancient and modern: time, culture and indigenous philosophy, UNSW, Sydney.

- Grosz E, 1994, Volatile bodies: towards a corporeal feminism, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- Heidegger M, 1962, Being and time, (trans. J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson), Harper & Row, New York.

- Holden J, 2008, Democratic Culture, Demos, London.

- Kester G.H, 2006, ‘Another turn’ (Response to Claire Bishop), Artforum International 44 (9), p22

- Kester G.H, 2011, The one and the many: Contemporary collaborative art in a global context, Duke University Press, Durham & London.

- Kwon M, 2002, One place after another: site-specific art and locational identity, Massachussetts Institute of Technology Press, Massachesstts.

- Lepecki A, (ed.), 2004, Of the Presence of the Body: Essays on Dance and Performance Theory, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT.

- Malpas J, 1999, Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography, Cambridge University Press

- Martin R, ‘Dance and its Others: Theory, State, Nation and Socialism’, in Lepecki (ed.) 2004, Of the Presence of the Body, pp47-63

- McDowell L, 1999, Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies, Polity Press

- Merleau-Ponty M, 1968, The Visible and the Invisible, Northwestern University Press, Cambridge.

- Morrison Z, 2010, ‘On Dignity: Social inclusion and the politics of recognition’, Social Working Paper No. 12, Brotherhood of St Laurence, Melbourne.

- Orr J, 29/6/2009, Interview with Gretel Taylor, Melbourne

- Orr J, 2003, From the Sea video installation, Warrnambool Gallery, Victoria.

- Orr J, 2007, The Crossing performance, Mildura festival, Loch Island, Mildura.

- Potter E, 2005, ‘The Anxiety of Place’ (review of Peter Read, Haunted Earth), Colloquy text theory critique, Monash University, Melbourne, pp. 124-129

- Powell M, 2010, ‘The inclusive aesthetic – inclusion is not just good for our health, it is good for our art’, Local-Global: Identity, Security, Community, Vol. 7, pp. 198-208

- Reid D, 2001, (thesis) Cutting Choreography: redefining dance on screen, Deakin University

- Sontag S, 1966, Against Interpretation: and other essays, Picador

- Taylor C, Appiah K, Habermas J, Rockefeller S, Walzer M & Wolf S, 1994, Multiculturalism: Examining the politics of recognition, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Taylor G, 2009, (thesis) Locating: Place and the Moving Body, Victoria University

- Taylor G, 2012, ‘Dancing Country Two Ways’, Writings on Dance 25

- Warr D, Kelaher M, Feldman P and Tacticos T, 2010, ‘Living in ‘Birdsville’: Exploring the impact of neighbourhood stigma on health’, Health and Place 16, pp. 381-388

- Warr D, Taylor G, Jacobs K, (under review) 2017-18, ‘You Can’t Eat Art: Exploring a sociology-art practice for challenging poverty stigma’, The Sociological Review, London

Acknowledgements

Special thanks: A/Prof. Deborah Warr, City of Wyndham, Dianne Reid, all 73 performers, Bec Cole, Rahima Hayes, Sally Beattie, Bonnie O’Leary, Uncle Reg Abrahams, Ruth Milhelic, Louise Holley, performers’ families, McCaughey Community Wellbeing Unit, University of Melbourne.