Coventry University, UK

Abstract

Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre (1979–1989) was a significant company in the development of dance in Ireland, and the first state funded contemporary dance group. For a period, the company were leading innovators in the country in contemporary dance and explored the boundaries of what constituted the dance form, leaving a lasting impact on Irish dance heritage, although relatively little has been written about their work to date. This paper explores the context for the company’s work, discussing the relationship between the body and language in Irish social, political and cultural history. Specifically, I focus on their production Bloomsday based on James Joyce’s Ulysses, which reveals key issues about the relationship between body and language in the company’s work.

Keywords: contemporary dance, Ireland, Joyce, language

Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre: background

In the late 1970s, Dublin-born dancer Joan Davis renovated a family property in order to construct a dance studio, which became Dublin Contemporary Dance Studio. Here, Davis and fellow dancer Karen Callaghan taught contemporary dance classes along with devising short pieces which were performed at local arts centres and schools around the country. Within two years, they set up Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre (DCDT), the professional performance company which toured regularly within Ireland and occasionally abroad. Callaghan departed to New York to study with Merce Cunningham, although she returned occasionally to choreograph works for the company. The core company members since 1980 along with Davis included Robert Connor and Loretta Yurick (who now run Dance Theatre of Ireland). Other members of the company at different times who continue to be prominent figures in the field of Irish contemporary dance include Mary Nunan, Finola Cronin and Paul Johnson amongst many others throughout the ten year span of the company.

DCDT regularly devised scores that incorporated movement and text, such as Word Works (DCDT, 1985), which included narratives on contemporary life in Ireland, and Modern Daze (Nina Martin, 1989), which explored a self-help, therapy obsessed culture. Along with writing new pieces, the company also drew on existing texts, for example, using Yeats’ prose and poetry for Lunar Parables (Pearson, 1984) and basing Search (Nunan, 1983) on Beckett’s Company. The Irish theme of these pieces is apparent, although the company also created works with a less specifically Irish context. For example, they presented a montage of film, music, and movement called Single Line Traffic (1986) choreographed by Japanese-born/New York-based Yoshiko Chuma and Tango Echo Brava November (1983) on the theme of American politics originally choreographed by Martha Bowers for the New York company Dance Theatre Etcetera. DCDT brought over choreographers and guest teachers from abroad on a regular basis in order to broaden the range of dance techniques available to the company and their students. Company members Loretta Yurick and Robert Connor originally came from America and had trained at the Centre for Performing Arts in Minneapolis, while Joan Davis trained regularly at the London School of Contemporary Dance. In addition, some dancers with DCDT came from abroad for periods of time to work with the company or came from Ireland but travelled abroad to get training before returning to work with the company. DCDT emerged during a period when Irish artists were increasingly making contact with companies in Europe and America and bringing back new methods of working (Sweeney, 2008). At the same time, DCDT attempted to explore what they described as ‘an Irish-reflected basis for contemporary dance’ (Connor in Taplin, 1985).

DCDT could be described as the first contemporary dance company in Ireland, although Aoife McGrath (2013, p. 37) points out a number of ‘danced precedents’ or practitioners who brought experimental movement practices and modern dance forms to an Irish context in earlier periods. However, these forerunners do not seem to have survived very long nor made such a long-term impact as DCDT. In fact, the fluctuating wave of modern and contemporary dance developments in Ireland has been described as a ‘culture of loss and recovery’ (Seaver, 2006, p. 36-37). 1 During the years that DCDT survived, they introduced contemporary dance to a wide audience by touring to theatres and schools on a regular basis. The company also offered training and performance opportunities to some of today’s important dance figures in Ireland. Managing director of Dance Ireland and previous company member, Paul Johnson (2002, p. 35) says that ‘it is due to the tenacity and visionary work of DCDT co-founder Joan Davis that we have a dance culture. Many of our current dance personalities … can trace their dance heritage back to DCDT and its studio’. However, funding was a continuing issue for dance in Ireland and DCDT’s Arts Council grants were completely cut in 1989. The company subsequently closed down and dancer Mary Nunan (2009) notes how the closure caused a ‘gap in terms of opportunities for young dancers to come through a repertory kind of ensemble’. In addition, although DCDT marked out a space for contemporary dance in Ireland through providing training and introducing audiences to the dance form, their work has not been documented and analysed in depth to date.

Context: the ‘postcolonial franchise’ and globalised identities

Bernadette Sweeney (2008, p. 194–195) argues that Ireland’s postcolonial position has impacted the development and documentation of performance that focuses on the body and movement, stating that ‘the importance of language for a postcolonial society has foregrounded the text at the cost of a suppressed body’. Sweeney (2008, p. 194–195) also comments that ‘the literary discourse ensures that written language has an exchange value and is a tangible proof of cultural endeavour and cultural difference. Recording and acknowledging the performative as part of a cultural tradition are difficult tasks’. In addition to the emphasis on the circulation of the literary text in building a national culture, the strong relationship between post-independence Irish national identity and Catholicism contributed to a conservative attitude towards cultural production. The threat of immoral behaviour to Irish national identity resulted in the control of dance in social and cultural contexts. As J.H. Whyte (1980, p. 25) notes that ‘of all the new fashions in post-war Ireland, the one which the bishops seem to have feared most was the mania for dancing which spread across the country, and which led to a rash of small dance-halls’.

In 1935, a Dance Halls Act was passed to prohibit dancing in unsupervised spaces, suggesting that the Church and State were trying to moderate bodily expression, which might lead to sexual arousal and therefore sexual activity. The act was also passed at a time when jazz music and ballroom dance (linked with bodily contact and expressive movement styles) were becoming popular in Ireland, indicating a resistance to outside influence because of the presumed risk to the values and stability of Catholic national identity. In addition, The Irish Dancing Commission, set up in 1930, strove to maintain the traditional form of Irish dance separate from outside influence 2 , and was bound up with Catholic ideals of morality. Modern dance, on the other hand, came from abroad and did not always fit with Catholic ideas of decency. Anecdotal evidence of negative attitudes to the dance form exists in Jacqueline Robinson’s (unpublished, p.8) writings on her experience as a pupil of modern dance teacher Erina Brady, when she states that ‘it does seem that there was a definite prejudice against theatrical dancing on the part of the more conservative section of the community, and of several members of the Catholic Church’.

Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins (1996, p. 215–216) note that ‘women’s bodies often function in post-colonial theatre as the spaces on and through which larger territorial or cultural battles are being fought’. This is certainly evidenced in Irish theatre, as Brian Singleton and Anna McMullan (2003, p. 9) note: ‘Woman in twentieth-century Irish theatre has been iconicised from the outset, either as a patriotic Cathleen Ní Houlihan figure, stirring the young men of Ireland to arms, or as the young innocent Aisling figure of purity’. The relationship between nationalism and women’s bodies can also be seen in the Irish constitution of 1937, where the role of women in Irish society included child-bearing and home-making. The constitution states that ‘the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved’. 3 The ‘danced precedents’ recorded by McGrath were primarily initiated by women and were therefore restricted in several ways: the fact that women’s bodies were ideological sites which represented nation; the links between body, immorality and the dangers of sexual expression; the representations of women in currency on stage; and finally the primary ‘place’ of women in the home.

While many researchers have drawn on postcolonial theory to discuss cultural production in Ireland, Patrick Lonergan (2009, p. 30) challenges the ‘postcolonial franchise that has dominated Irish Studies, proposing that ‘we need a new framework for understanding contemporary developments in theatre in their social and cultural contexts’. Although it is crucial to consider how a postcolonial heritage affected the development of dance in Ireland, DCDT’s work also represents the effects of a developing globalisation in the country. In the decades prior to the establishment of DCDT, Ireland went through vast changes, which made it possible for the company to develop. The Catholic Church, an institution that had for so long been a dominant influence on the state, struggled with changes to this status, and the conflict was played out in the cultural arena. Ireland’s economic strategy also altered radically, as the government moved away from the previously protectionist attitudes to the national economy, emphasising trade agreements with other countries. This went in opposition to the prior aim of the nation state to establish a distinct and separate Irish identity through differentiation from outside influences, especially that of the coloniser. Lonergan (2009, p. 24) notes that ‘the current period of globalization in Ireland has its roots in the 1950s, when the government’s decision to embrace economic globalization unleashed a process of cultural globalization’.

Changes in social and political conditions in Ireland at the time when DCDT emerged opened the way for cross-fertilisation of ideas from Ireland and abroad. In addition, the gradual lessening control of Catholic morality over Irish culture meant that the exploration of the body and movement became more easily acceptable on the Irish stage. A more radical split from the Catholic Church can be marked after the Celtic Tiger era and also in the wake of abuse scandals in the 1990s (McGrath, 2013), but at the same time there was quite a marked shift in the decades directly before DCDT was founded. Inglis (1998, p. 246) notes that ‘from the end of the 1950s the state began to pursue economic growth through increased industrialisation, urbanisation, international trade, science and technology. The growth of the media brought enormous changes to family and community life....The media and Catholic Church have changed positions’. The impact of the media on consumer’s choices in Ireland can be seen, for example, as trends from Fame to aerobics influenced DCDT’s income from dance classes, as Davis (2007) states:

The timing was amazing because it was right when Fame, the Musical came out and everybody wanted to be in leotards … we were swept up on that, and then of course aerobics came in and they took all our customers away.

While Irish culture was transforming because of economic development and the increasing impact of the media, attitudes towards the role of women in Irish society were also changing. Women were now acknowledged as having a role in the workplace and the nation’s economic expansion. The marriage bar, which meant that women in civil service had to resign from their job on marrying, was lifted in 1977. In 1979, a bill was passed so that contraception, which had previously been banned, could be obtained on prescription, albeit under regulated conditions. These initiatives reflected the changing attitude of the state towards the role of women in Irish society and the increasing separation of Church and State in the conceptualisation of Irish identities.

In addition, the new Arts Act was set in motion in 1973, making changes in the Arts Council of Ireland for the first time since it had been formed in 1951. At that time, there were three subsidised theatres in Ireland—the Abbey Theatre, the Gate Theatre, and the Lyric Theatre in Belfast (Morash, 2002). In the following decades, this altered considerably, with the government supporting smaller companies, thereby creating alternatives to the mainstream. Christopher Morash (2002, p. 271) comments that increased state funding for theatre from the 1960s to 2000 allowed representations of the nation to diversify, stating that ‘spreading this money among more than forty companies who now receive funding (to which can be added almost fifty non-subsidised companies) means that Irish theatre is now more fragmented and makes fewer claims to represent an entire nation than ever before’. The founding of Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre in 1979 and their funding by the Arts Council of Ireland can be seen to be part of the new wave of companies whose work broadened representations of what constituted Irish culture. At the same time, the tradition of literature and theatre in Ireland has been used to promote the cultural status of the country (e.g. Joyce and Beckett), and traditional Irish step dance ‘became a focal point for Irish cultural representation’ (Foley, 2001, p. 35) in the founding of the nation state and more recently in globalised culture through shows such as Riverdance. However, contemporary dance has struggled to develop and to be recognised, which is made apparent in the continuing infrastructural issues such as lack of funding, dance spaces and training opportunities. However, changes to the Irish economic, social and cultural system provided a space where DCDT could take root, create work with international choreographers, introduce new techniques, and negotiate changing Irish identities, influenced by media, travel and the internationalisation of markets.

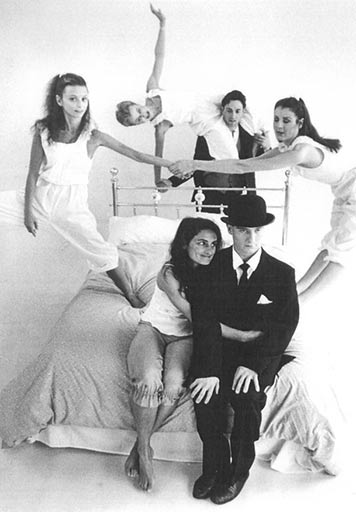

Bloomsday, Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre/Jerry Pearson, photographer unknown. From the DCDT archive, Dublin, 1988. Permission from DCDT members Joan Davis, Loretta Connor and Robert Yurick.

Bloomsday, Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre/Jerry Pearson, photographer unknown. From the DCDT archive, Dublin, 1988. Permission from DCDT members Joan Davis, Loretta Connor and Robert Yurick.Bloomsday: fleshing out the bones of Ulysses

DCDT’s production of Bloomsday: Impressions of James Joyce’s Ulysses was presented at the Dublin Theatre Festival in 1988 and is illustrative of the changing attitudes towards the body and sexuality in Irish culture. It combines Joyce’s previously ‘obscene’ and now canonical text with a physicalised vocabulary, and the production was a critical success although the company closed down the following year due to funding cuts. The production was choreographed and directed by Jerry Pearson, an American choreographer who had previously worked with Nikolais Dance Theatre and the Murray Louis Dance Company, before founding the Pearson Dance Company, which toured around the world. He had an interest in Irish themes, which was an important aspect of DCDT’s programme and had choreographed a number of works for the company such as Lunar Parables in 1984. Bloomsday exemplifies a number of the main strands that run throughout the DCDT’s work. Along with working with an international choreographer on an Irish theme, the integration of text with movement was pertinent to the company who were presenting contemporary dance to an audience who were more familiar with text-based performance. As Loretta Yurick (2008) notes: ‘we did a lot of works with words, I think because we felt that was a way to help people make what we were doing more accessible’. In fact, the company’s work often crossed disciplines of visual media, dance, theatre, and sound—and likewise, Pearson incorporated dancing, acting and singing as a defining feature of this production of Bloomsday.

In a video recording of Bloomsday, the production opens with a chatty and vivacious Malachi Mulligan played by actor Séan Campion, with his face covered in shaving foam, making signs of the cross with a cut throat razor and mumbling blessings mockingly. Stephen Dedalus appears, played by DCDT dancer Robert Connor—hands in pockets, silent and brooding. Whenever Mulligan leaves the space, Dedalus starts to dance on his own. He swings his right arm into the air, letting it drop with a weight that turns his body in a full circle, and then he leans his body backwards in a fluid movement. The verbal loquacity of Malachi is contrasted with Dedalus’ covert movement phrases, as a language for expressing his exuberance. Pearson notes several practical issues in staging Ulysses, including the need to cut the text for staging purposes and to utilise the skills of the dancers, actors, and singers to their best advantage (Pearson, 2014). Within an Irish context, however, it is still an interesting choice to make Dedalus ‘mute’ in the production, particularly as Dedalus is often assumed to represent Joyce.

In an early scene, a series of projected slides say: ‘It is 8am, 16 June 1904. 7 Eccles Street. Leopold Bloom and Molly’. We see the couple asleep in a large bed. Bloom, played by dancer Paul Johnson, wakes up and the full process of his morning ritual is staged before the audience: putting on his trousers, buttoning his shirt, pulling on his socks, tying his shoe laces, and pulling up his braces. The extended use of pedestrian movement evokes both the punctuation of everyday activities and the potential monotony of the couple’s married life. To accentuate this, Bloom fills a kettle, lights a flame, puts the kettle on the boil, all in real time with material objects. Rather than conveying a type of ‘naturalism’, it allows a slowing of time to appreciate the textures of everyday movements that are informative for the rest of the production. Bloom returns to the bedroom to give his wife Molly, played by singer Joan Merrigan, a letter but she asks him for tea. When he returns with the tea, she hides the letter under her pillow. Simple movement actions are choreographed into a telling sequence, as the scene shows the care by Bloom for his wife in the small gestures he makes, but also Molly’s secrecy.

Later scenes physicalize the sexuality suggested in the text such as Molly’s affair with fellow singer Blazes Boylan, played by Philip Byrne. A slide says: ‘Tenors get all the women’ as Boylan enters the Blooms’ Eccles Street home. Molly and Boylan sing the duet ‘Là ci darem la mano’ 4 from Don Giovanni by Mozart where the protagonist tries to seduce the lady. An onstage narrator bluntly summarises that the meaning of the lady’s response to the seduction is: ‘I might, then again I mightn’t’, which contrasts with the famous ‘yes’ speech by Molly later in the book that suggests sexual acquiescence. The exchange between the singers as they enact the scene seems quite formal rather than passionate—she gets under bedcovers in a full-length nightgown while he pulls down his trousers. He tries to touch her but she pushes his hands away. The choreography plays with the push and pull of desire and power as the contract for this illicit sexual encounter is negotiated. Towards the end of the scene, the pair comically pull the bedcovers over both of their heads. In the book, the affair is alluded to and imagined, while the performance risks visually showing it in view of the audience. At the same time, the imagination or memory of the characters in the book identifies the affair as highly erotic, in contrast with the staged performance where the couple appear giddy and gauche. The staging choices invite the audience to laugh at the couple’s actions, as there appears to be a slight awkwardness in the physical contact between the characters. However, it shows a liberal attitude towards sexual behaviours, which might have been out of place on the Irish stage in previous decades.

A later scene portrays the sexually explicit potential of staging segments of the book. In Joyce’s text, the internal dialogue of the young woman Gerty MacDowell allows her to fantasise through language (and potentially visual imagery in the mind of the character and therefore the reader). However, in the production, the internal dialogue voice is represented by a live voiceover of actress Sarah-Jane Scaife while DCDT dancer Loretta Yurick physically portrays the character. Sitting by the seaside, Gerty notices Bloom opposite her and she imagines him as her dream husband, fantasising that she has ‘raised the devil in him’. She looks up to the sky to watch fireworks, which are taking place nearby, exposing her ankles as she leans back on her seat. Bloom starts rubbing his knees and legs vigorously as he looks at Gerty. The lighting darkens as we enter her imaginary world and the tempo of the female storyteller’s voice quickens with Gerty’s physical arousal. She cycles both her legs in the air, slowly allowing her dress to reveal her calves and thighs. Crowds can be heard ‘oohing’ and ‘ahhing’ at the fireworks in the background which mixes with Gerty’s sighs and moans of ecstasy. However, Gerty is called back to reality by her friends. She noticeably limps off the stage and drops her head as Bloom watches her leave, suggesting a shame both of her sexual desire but also the stigma of her physical disability. While this scenario divides up the role of speaker and mover, the physicality is supported by the increasing tempo of the narrator’s voice, the projection of the fireworks, the soundscape and the lighting. The movement score reveals both Gerty’s physical and imaginative capacities (and disabilities), while the actor’s voice imagines the sexual excitement as much as the dancer’s body. Through the staging of the piece, it also seems significantly focussed on the desires of the young woman rather than on Blooms’ arousal, offering a space to explore female sexuality.

Movement, physicality, sexuality, and the various uses and abuses of language through literature, law, and religion are intermingled in Pearson’s production. Joyce’s text deals with these issues and DCDT’s stage production responds to them by exploring further nuances through the material actualisation of the scenarios. One scene depicts DCDT founder Joan Davis as prostitute Bella Cohen, bringing Bloom through a rollercoaster of desire, pain, repression, and expression that emerges from the shifting pressures and pleasures of body and language. Two prostitutes hold Bloom down while Cohen interrogates him, grasping his face in her hands. Moving between dialogue and movement, they engage in sadomasochistic play: he falls to the ground and she stands over him with her foot on his shoulder; he leaps up and runs after her crying ‘exuberant female’; she orders him onto his hands and knees and he starts barking like a dog. The prostitutes scream with laughter and play games, sometimes jokingly like when Cohen smacks his bottom asking ‘how’s the tender behind?’ and sometimes violently as when she pulls his arm backward saying ‘I will hurt you’. Finally, two prostitutes hold Bloom down while Cohen extinguishes a cigarette on him—he leaps up onto his hands and knees and cries in pain while she sits on his back and laughs. Extreme vocal and physical behaviour appears to erupt from the multiple pressures of reason and impulses of desire, which push him over the edge.

At the end of the production, Bloom drunkenly wanders home and falls asleep beside Molly. A soundscape starts: inaudible utterances, sharp intakes of breath, and a tirade of words unfold. Several layers of the voice and breath are overlaid so that it becomes an array of voices, creating a night time dreamscape. We start to realise that this is the voice of Molly Bloom, as a more distinct vocal layer is heard repeating the well-known ‘yes’ segment from the end of Ulysses. At this stage, Molly has awoken and is looking at Bloom, as the voiceover says ‘I took more pleasure leading him on til I said yes’. Unlike other scenes that try to show a physical representation of what the text imagines, here the text is ‘embodied’ in voice while bodies appear to inhabit another parallel world. A procession of ghosts of characters from the story circle the bed, as the voiceover continues, blending dreamlike vocal and visual scenographies. The voices and bodies are like an outpouring of thoughts running through Molly’s mind, transforming from an internal monologue to a mirage of influences, characters, and scenes from her life. The multiplicity in this scene hints at the disintegration of the monologic authorial voice suggested in Joyce’s text, towards a sense of the multi-dimensionality of experience as it layers across self, others, places, and events.

This large production of Bloomsday was successful and celebrated in many reviews, with bookings for the show filling almost at full capacity for the duration of the run. Carolyn Swift (1988) declares the production ‘a triumph for Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre’ while Mary MacGoris (1988) nominates it as ‘possibly the most painless Joyce of the century’. MacGoris continues: ‘Bloomsday as presented by Dublin Contemporary Dance Theatre, joyously fleshes out the bones of Ulysses while relieving them some of the larding of self-regarding loquacity’ indicating a complex relationship with Ireland’s literary heritage. While it may not have been the choreographer’s intention to cause competition between the physicality of the piece and Joyce’s text, this review highlights the dialectic between language and movement that occurs in many reviews of the company’s work. At the same time, the work was deemed ‘provocative too, but mildly so’ (Brogan, 1988), suggesting that the company’s embodiment of Joyce’s text was acceptable rather than subversive. In a society where bodily expression had previously been a taboo subject, changes had obviously taken place in the country. On the production, critic Teresa Brogan (1988) states that ‘it’s the best possible antidote to the Top of the Morning stage Irish image of Paddy abroad, and yet cry for shame, it was devised by an American’. The presentation of an Irish text produced by an American choreographer is stated as challenging stock representations of Irishness, suggesting that the cultural capital of that particular brand of ‘Irishness’ had become out-dated.

Changes to Irish society can be seen in comparing DCDT’s production with another attempt to stage Joyce’s writing in the early years of the Dublin Theatre Festival. Unlike DCDT’s production of Bloomsday in 1988, a theatre production of Ulysses at the festival of 1958 was cancelled due to complaints by a senior representative of the Catholic Church, Archbishop MacQuaid, about the ‘inclusion of this “obscene” and “objectionable” material’ (Grene and Lonergan, 2008, p. 227). In 1957, the first Dublin Theatre Festival had suffered similar issues, with the arrest of Alan Simpson for his staging of Tennessee William’s The Rose Tattoo at the Pike Theatre. The production involved a pre-marital seduction scene where a condom was allegedly dropped on the stage and Simpson was charged with ‘presenting for gain an indecent and profane performance’ (Simpson, 1962, p. 148). Lionel Pilkington suggests that the closing down of Simpson’s performance represented wider tensions arising from the social changes where the state was slowly separating from the Church. He says that,

In many ways, therefore the arrest of Simpson was itself a dramatisation of the ideological battle that was taking place in the 1950s: between an expansionist state agenda (championed by politicians like Lemass and senior civil servants like Whitaker) and the defensive reactions of dominant elements within the Catholic Church (Pilkington, 2001, p. 157).

By 1988, when DCDT staged their adaptation of Ulysses, attitudes to representations of sexuality and the body had vastly changed. Joyce’s book had become a canonical and widely acceptable text, adopted as a valuable source in promoting Ireland as a culturally rich country. Reviewers of DCDT’s Bloomsday, in fact, commented that the production had updated the classic and challenged the image of what represented Irishness, while the sexual references were only considered mildly provocative.

Conclusion: body, language and archive

The changing economic and political situation in Ireland in the years prior to the founding of DCDT impacted Irish identities and meant that the company could survive without the extreme levels of censorship to dance apparent in the nation’s early history. 5 DCDT built on these conditions to educate their audience and performers through dance classes and schools programmes, touring Ireland and abroad, inviting guest choreographers and providing a starting point for dancers to go on to further training or set up their own companies. Bringing together this increased mobility and shifting nature of identities within an Irish landscape, the company explored Irishness through contemporary techniques, updating representations of national identities, and playing with ideas about what constituted dance performance. Despite the fact that the company was the national representative of contemporary dance for a period of time, highlighted by support from Arts Council reports, documentation of the company’s productions is limited. Revisiting and rewriting histories is necessary to indicate the ways in which previous accounts of history have been selective and for what reasons. I would like to argue for the significance of DCDT in Irish performance history, and as such the importance of the documentation of the company’s work. While DCDT adapted their work in an attempt to make it more accessible to an Irish audience, they also played a considerable part in introducing Irish performers and audiences to contemporary dance forms. The company’s work not only represented issues that arose at the time surrounding language and movement in performance, but also altered the performance landscape as a catalyst for new forms of expression in Ireland.

Video recordings of the DCDT performance of Bloomsday were made available to me by Loretta Yurick and Robert Connor at their Dance Theatre of Ireland venue in Dun Laoghaire, County Dublin, where the chairs from the production are still in use twenty-five years later. Meanwhile, Jerry Pearson, who is now Professor of Dance at University College Santa Barbara, tours with his production called Body of Work that reflects on the performed history of a lifetime, referencing his time with DCDT. He recently performed at the University of Limerick in Ireland where previous DCDT dancer Mary Nunan is now course director of the M.A. in Contemporary Dance Performance. In Wicklow, Joan Davis has sent her DCDT photographs and reviews to the important new National Dance Archive of Ireland, while making a somatic-influenced dance film called In the Bell’s Shadow, which includes Nunan and a new wave of local and international practitioners. During the process of research, I have also become enfolded as a participant in the company’s work and in 2014, I began work with Davis, Nunan, Yurick and Connor on a project that explores the embodied archives of DCDT. The research and writing process is part of a complex series of exchanges, which I hope can reinvigorate the (bodily and imaginary) memories of the productions and stimulate further dialogue. In this first instance of an in depth exploration of DCDT’s piece Bloomsday, my writing reflects on key contextual issues which might need to be considered in understanding their work. As my research on the company’s work expands, there are further layers of material to share—the sensorial and intersubjective process of research; the thoughts, feelings, and actions stimulated by contact with the company’s work; and the embodied histories that continue to permeate Irish dance culture today.

References

- Brogan, T. (1988, October 5). Bloomsday so stimulating! Evening Press.

- Connor, R. (1985). In D. Taplin (Ed.). One’s company. The Sunday Tribune, May 19.

- Davis, J. (2007) Interview by author. Dance House, Dublin, May 23.

- Foley, C. E. (2001). Perceptions of Irish Step Dance: National, Global, and Local. Dance Research Journal, 33 (1), 34-45.

- Gilbert, H. & Tompkins, J. (1996). Post-colonial drama: theory, practice, politics. London and New York: Routledge.

- Grene, N. & Lonergan, P. (2008). Interactions: Dublin Theatre Festival 1957–2007. Dublin: Carysfort Press.

- Inglis, T. (1998). Moral monopoly: the rise and fall of the Catholic church in modern Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 1998.

- Irish Constitution/ Bunreacht na hEireann (1937). Articles 4.1, 2.1 and 2.2. 1937, with amendments up to 2004.

- Johnson, P. (2002). Dancing in the dark. Irish Theatre Magazine, 3 (12), 34–38.

- Lonergan, P. (2009). Theatre and globalization: Irish drama in the Celtic Tiger era. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacGoris, M. (1988, October 5). ‘A painless case.’ Irish Independent.

- McGrath, A. (2013). Dance theatre in Ireland: revolutionary moves. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Morash, C. (2002). A history of Irish theatre, 1601–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nunan, M. (2009). Interview by author. Dance House, Dublin.

- Pearson, J. (2014). Interview by author. Brown’s Café, Coventry.

- Pilkington, L. (2001). Theatre and state in twentieth-century Ireland: cultivating the people. London & New York: Routledge.

- Oireachtas/ National Parliament Dance Halls Act. (1935). Retrieved 6 July 2009 from: http://acts.oireachtas.ie

- Robinson, J. (unpublished). Dance in Dublin in the 1940s. Manuscript available at the Dance Ireland Library, Dublin.

- Seaver, M. (2006). Loss and recovery. Irish Theatre Magazine, 6, (27), 36–38.

- Simpson, A. (1962). Beckett and Behan and a theatre in Dublin. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul.

- Singleton, B. & McMullan, A. (2003). Performing Ireland: new perspectives on contemporary Irish theatre. Australasian Drama Studies, 43 (October), 3-15.

- Sweeney, B. (2008). Performing the body in Irish theatre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Swift, C. (1988, October 5). Bloomsday at Lombard Street Studios.The Irish Times.

- Whyte, J.H. (1980/1971). Church and state in modern Ireland, 1923–1979, Dublin: Gill and Macmillan; London: Macmillan.

- Yurick, L. (2008). Interview by author. Dance Theatre of Ireland Studios, Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin.

This article has not been published, submitted, or accepted for publication elsewhere.

© 2015 Emma Meehan