Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Abstract

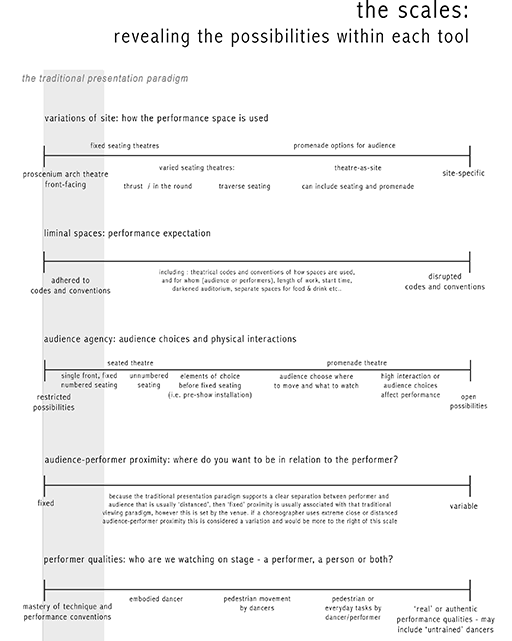

This research questions how a ‘lived experience’ of contemporary dance could be deepened for the audience. It presents a series of choreographic ‘tools’ to create alternative frameworks for presentation that challenge the dominant modes of creation, presentation and meaning making in contemporary dance. The five tools established and applied in this research are: variations of site, liminality, audience agency, audience-performer proximity and performer qualities. These tools are framed as a series of calibrated scales that allow choreographers to map decisions made in the studio in relation to potential audience engagement. The research houses multiple presentation formats from the traditional to the avant-garde and opens up possibilities for analysis of a wide range of artistic dance works. This research presents options for choreographers to map how audiences experience their work and offers opportunities to engage audiences in new and exciting ways.

Keywords: audience engagement, choreographic tools, dance, choreographic practice, audience participation

Introduction

This research considers how the creation and presentation of contemporary dance affects audience engagement by positing the body of the audience member as a site of meaning making from the inception of a creative work, rather than after the work has been created. It unpacks how we traditionally present western contemporary dance, questions how artists might engage audiences with a variety of different models, and directly links the presentation format of dance to audience engagement.

How is live performance viewed? How is it experienced? Is there a difference between viewing and experiencing contemporary dance, and what elements could be varied to impact audience experience? Many artists working in the genre of live art, performance art and contemporary performance manipulate traditional presentation formats to vary audience engagement with their work. The extreme end of these examples include: La Fura Dels Baus who brandish chainsaws at their audiences; Blast Theory who kidnap audience members; Mammalian Diving Reflex who cut audience members’ hair; or Franko B who mutilates his body in close proximity to the audience. 1 In the genre of artistic dance 2 however, many choreographers are still working within traditional seated, front-facing modes of presentation. While a series of dance movements in the 20th century shifted artistic dance outside this presentation format, many of the choreographers who are dramatically altering the traditions of their art form work in areas of live art, performance or installation. 3 While artform definitions may seem unnecessary or obsolete, particularly in light of the experiments of the Judson Dance Group artists (amongst many others) in the 1960s, and choreographers such as Xavier le Roy or Jérôme Bel who strive to create indeterminate dance works, 4 there is an assumption that some current contemporary art practices, including dance, are unable to connect fully with contemporary audiences. 5 If this is the case, then what do the makers of contemporary dance need to address if we are to begin to re-connect to our audience?

This paper looks at some of these issues, including: the global impact of proscenium arch theatres on active audience engagement; whether contemporary dance makers can engage audiences on a phenomenological level; and how choreographers can challenge the seated, passive 6 performance model. This research focuses on contemporary artistic dance created in the west, and dance works presented in major proscenium-arch playhouses throughout the world.

The traditional presentation paradigm for contemporary dance

The traditional presentation format, in which much current artistic dance is presented, supports work that is made to be ‘received’ by a seated audience, who are in the dark, front facing with restricted or no agency. While ‘receiving’ is also used in communication studies models (see Fiske & Jenkins, 2011), in this context it refers to a performance that is presented to the audience (in a monologic format), irrespective of individual audience characteristics. ‘Passive’ in this context refers to this monologic of ‘receiving’, as well as limited physical and active choices available to the audience. As Susan Kattwinkel (2003, p. ix) observes of contemporary audiences: ‘The spectator is generally relegated to ‘receiver’ status, having little impact on the process of performance except in standard, structured response’.

This presentation format also supports dance works that are usually 60-90 minutes in length and created to be tour-ready for equivalent theatrical architecture throughout the world. 7 While many choreographers from non-western countries create work within this dominant paradigm (with similar conventions and presentation format), they often localise their work with geographic and cultural concerns outside that western framework. However, these artists often create and then present work within this established paradigm, so while the movement and content may vary, the way in which the audience engages with the performance does not. For example, many Indigenous choreographers in Australia are creating works with specific cultural concerns and innovative choreography that draws on their culture, but they are, mostly creating work to be presented within the western traditional presentation paradigm. 8

This particular way of viewing dance was developed in the 19th century when theatres were redesigned to accommodate innovations in electrical lighting allowing for a lit stage and a darkened auditorium. Seated auditorium rows were introduced for better sightlines and proscenium arches framed the performers’ action on stage (separating the performer and audience), making theatres front facing. These 19th century innovations are reflected in the theatres we still use today. 9 This architecture, however, rarely allows for deviations in presentation format and has a profound effect on the choreographic process. Gay McAuley (1999, p. 236) proposes that it is the physical space of these theatres that provides both ‘the fundamental condition for spectatorship and the major variable determining the nature of the theatre experience’.

This particular type of theatrical experience is commonly reinforced by touring circuits, economics and habit, rather than by the needs of a particular work, concept, or audience. 10 Irrespective of cultural differences, this traditional presentation format is seen throughout the world, with duplicate theatres on every continent. I refer to this presentation format as the traditional presentation paradigm.

The variations of presentation formats

In many countries the 1960s were characterised by unrest, revolution, empowering political movements and the upheaval of established governments. The arts were intimately involved with these changes—the Cold War, feminism, socialism, black rights and anti-war movements. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, a major choreographic revolution took place within contemporary dance in the west (predominantly in the US) transforming how and where dance could be engaged with. Dancers performed on rooftops, in parks, and in warehouses, and they opened up the idea that any bodily movement, if it had intention, could be dance. There are myriad examples of audience interaction, audience participation and audience manipulation works from this period that challenged what dance could be and the roles audiences played in this construct. 11

In the last 50 years, however, there has been a return to presenting within the traditional 19th-century model. Kattwinkel (2003, p. ix) suggests that, ‘The passive audience, of course, is a relatively new condition of theatrical experience, but nevertheless has become so prevalent that it is the status quo for most theatre in the West’.

Current choreographic experiments

While the radical experiments of the 1960s have faded from the everyday and a return to traditional forms of presenting dance are currently more common, 12 there are several notable artists throughout the world working outside this dominant presentation paradigm, questioning how audiences can engage with contemporary dance. But many artists are not. For many choreographers, their innovation comes from the content they put on stage rather than looking at the stage itself or at the presentation format as it is traditionally used.

Rather than looking to the content of a dance work and the innovative developments in this area (which include, amongst others, fragmentation, hybridisation, innovative collaboration, use of technology, varied use of narrative forms etc.), can shifts in the presentation form alter how a dance work is engaged with by the audience? This research posits that with shifts in the dominant presentation paradigm, audiences do engage differently with contemporary dance.

However, challenging these inherited paradigms is expensive, can be limiting in terms of touring and many theatres do not support formats that are created for small audience numbers, one-on-one performances or allow audience on stage. But if there is research to suggest that audiences may be diminishing for contemporary dance, 13 perhaps we should look at engagement of audiences as more complex than just offering cheap parking or access to childcare as some venues suggest.

The audience’s body as a site of understanding

I have been creating dance and performance work for over twenty years, and from my observations of audience, it has become clear that often an audience’s level of connection with the work is related to their ability to physically interact with the work. This physicality may be via promenade theatre, site-specific works or simply a walk-through installation prior to the seated performance. Leslie Hill (2006, p. 48) suggests that, ‘Though conventional theatre-going is a real time, real space experience and thus has the potential to be sensually immersive, it is more often than not an audio-visual experience that offers little to the other three senses’. It is here that Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s interest in the body as a site of understanding the world seems relevant, not only to art makers, but also to the audiences of dance. Merleau-Ponty believes that the body is ‘inseparable from creative activity’ and that transcendence is ‘inseparable from bodily motion’ (in Levinas, 2003b, p. 14). His insistence that it is via our bodies that we engage fully with the world mirrors my observations of audiences who seem to engage differently with performance when they physically interact with the work. This observation has led me to unpack the physical, as well as the conceptual and metaphorical, role that audiences can play within the creative process.

If, in phenomenological terms, we experience the world via our bodies, then surely this type of understanding, an understanding via the body rather than only via the intellect, is an important and relevant aspect of communication within the live arts. While often taken for granted within the profession, the argument for the experiential to have an authoritative voice has recently been a prominent discussion amongst practice-based and practice-led researchers within some universities. 14 These discussions have served to support research practices based within non-linguistic frameworks and have been useful for those of us interested in audience engagement. But while there is now more research on how audiences and performers engage cognitively with dance, 15 there is a gap for both art makers and researchers in how different physical engagement or presentation models affect that engagement. Cognitive research suggests that understanding can be engendered in an audience intellectually, emotionally and experientially (via actual participation), 16 and as Oddey and White (2009, p. 9) observe: ‘When the spectator participates in the work, they become ‘fused with it’’. Meredith Monk says of this kind of art that it is ‘an art that cleanses the senses, that offers insight, feeling, magic. That allows the public to perhaps see familiar things in a new, fresh way—that gives them the possibility of feeling more alive’ (Monk, 1997a, p. 17).

The possibility of feeling more alive in a dance work

While it is established that the traditional presentation paradigm cannot engage the audience with all their senses, or engage via a physical bodily connection, there is little point in challenging a paradigm without offering an alternative. But the opposite of the traditional presentation paradigm for dance is just as limiting and prescriptive. To challenge the inherited, what is needed is a quantifiable framework, flexible enough to house the bewildering array of presentation formats available to choreographers—including the traditional. I have developed a series of choreographic tools that identify how we traditionally engage with presentation models and offer other options for presenting dance. Each tool focuses on an element of presentation that affects choreographic process and audience engagement. These tools are: variations of site, liminality, audience agency, performer-audience proximity and performer qualities. The scales allow choreographers to map those engagement decisions in the studio as the work is being made or to analyse the work after it has been presented.

The choreographic tools

Within the scales below, the traditional presentation paradigm is positioned on the left—indicating the use of each ‘tool’ that is accepted to have been inherited from theatrical frameworks developed since the 19th century. The variations on the far right of each scale represent the extreme opposite in terms of options available for engaging with performance, and usually house experimental or avant-guarde contemporary work. In between are the myriad presentation formats that engage audiences.

Below is a brief outline of each of these tools and the variables presented within these scales.

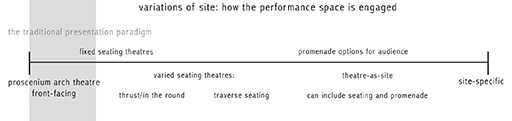

The scale of site

On the far left-hand side of this scale sit the majority of presentation options for choreographers: within a theatre, a seated audience who are front facing, in numbered seating, in the dark with limited or no agency. To the right of this traditional mode of viewing are theatres that, while still having fixed seating for audience and fixed proximity between audience and performer, are not front facing but in the round, on three sides of the stage, or more adventurously, in lines facing each other. These fixed-seat theatre options can also include un-numbered seating so the audience can choose where to sit in relation to the stage or performing space within the limited options available.

Further along the scale are promenade options for audience where seating is optional and the theatre is used as a site. This format engages the specific characteristics of the theatre and introduces audience agency by letting individuals choose where they walk throughout the performance. On the far right of this scale are performances created for site-specific environments. These performances remove the tradition of presenting dance works in a theatre entirely.

The space in which a dance work is presented is central to how an audience will engage with that performance. This choreographic tool affects all of the others, and variations of site are invariably entwined with variations of liminality, audience agency, audience-performer proximity and performer qualities.

All of these presentation possibilities have a major impact on how audience perceive the work and each variation has ramifications in terms of a lived experience for the audience.

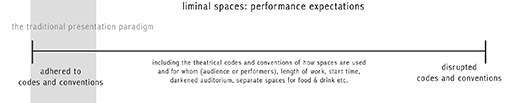

The scale of liminality

The word limen in Latin literally means threshold, and cultures throughout the world have used liminality in rituals to mark transformation between roles, such as from childhood to adulthood, single to married etc. Artists can create versions of this kind of transitory physical or metaphorical limen in live performance: environments where the codes and conventions of daily life are suspended, where audience roles are unclear and expectations are challenged. Artists use this tool to unsettle audiences, to open up different ways to engage with a work or to form new communities within their audience. Victor Turner (1988, p. 84) calls this a communitas of spectators who may never cross paths in daily life, but connect within the liminal space of a performance. Liminal spaces tend to disorient audience members, but disorientation (depending on how fast you can recover from it) is not always negative. If ‘the rules’ of a performance are discovered quickly and easily then sometimes disorientation can be liberating because it shifts audience from their old self into a new unknown self for the duration of the show.

Because liminality is focused on audience expectations, it is often used in conjunction with variations of site. Some examples would be to change the ‘expected’ use of individual spaces (i.e. to invite the audience on stage with performers), changing the ‘expected’ length of a work (i.e. to very short or very long), changing the ‘expected’ start time (i.e. very late etc.) or changing the ‘expected’ audience-performer ratio (i.e. one-on-one performance in a major playhouse). Works on the far right of this scale also often include audience agency and shifts in audience-performer proximity.

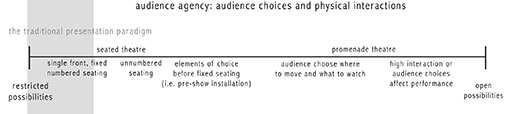

The scale of audience agency

When we look at audience agency within the traditional presentation paradigm for dance, it is often limited or non-existent: seating is usually numbered, proscenium-arch architecture precludes audience looking anywhere but front and non-participatory engagement is a widely accepted form of spectatorship. In this viewing format, active physical interaction on the part of the audience is virtually impossible. While we are active in making the choice to go to a performance, traditionally once we are in our seats our sense of agency is diminished. We are physically passive. That is not to say that we are unconnected or emotionally removed from the work. Classical ballets, for example, can be highly engaging and often work best seen in this viewing format. But the active physical nature of agency, and the implications in both our mind and body, is not usually part of dance presented within this presentation format. In fact, within this viewing format, the only physical choice available to an audience member is to stay or leave.

On the scale of audience agency the possibilities range from restricted to open. Performances on the far left of this scale incorporate the status quo where audience agency is ‘restricted’ or non-existent. On the far right of the scale are performances where the possibilities for audience agency are ‘open’. These works often include audience interaction or audience immersion. The myriad possibilities between these two extremes include works that allow the audience to choose where to sit or stand to watch the work, or promenade environments where audience need to make choices between competing performances within a single work. This scale represents the amount of choice offered to the audience to make individual decisions within a particular work. It also maps who is making these decisions: the venue, the choreographer or the spectator.

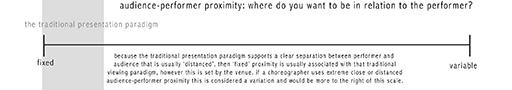

The scale of audience-performer proximity

In the middle of the scale are works where the audience proximity might be fixed, but the distance is unusually (in reference to traditional theatrical venues), close or far away from the performance. While audience agency may not be offered, the traditional presentation paradigm is being challenged because the distance spectators are from the performance is specifically connected to the content of the work. This means that it is the choreographer, not the architecture of the venue, who is making this decision.

Postdramatic Theatre theory suggests that it is the space between the performance and the audience (metaphorically and physically) where meaning is made (Lehmann, 2006). Whether this is the case in contemporary dance is an important question for choreographers working in a post-structuralist paradigm; however, for a number of reasons, both contemporary dance and ballet are usually seen from a fixed distance.

Changing the proximity between audience and performer changes what possibilities both parties have to engage with the other. One of the difficulties with presenting work within the traditional presentation paradigm is not that audience proximity is fixed per se, it is that it is always the same, irrespective of what work is being presented on stage. When proximity between audience and performer is actively considered, then the venue, seating arrangements and content all need to be questioned and the resulting work makes these connections central.

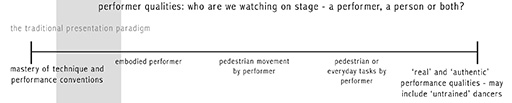

The scale of performer qualities

With historical precedents in theatre and post-modern dance, 19 the ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ dancer is a performer who is able to connect via immediacy, engaging audience not by illusion but through a visceral connection of the everyday.

For post-modern choreographers, the everyday was utilised to highlight the form of the work and the body as an everyday instrument, often in everyday situations. Pina Bausch took a different standpoint in her work: she utilised theatricality and front-facing theatres but asked her performers to undergo often difficult situations on stage, so we saw how they revealed themselves as people, which formed an unexpected and individual connection with the audience. Bausch’s dancers were still performing, but their ‘authentic’ performance quality was used as an engagement device. In his 2009 book about Bausch, Climenhaga discusses his audience experience:

For the moment sitting there in the dark I am stunned, oddly uncovered, and exhausted … Despite the artifice of the situation, the woman goes through a very real event, and her presence on stage is a product of both her actual existence in this moment, and the long and dense collage of images that lead up to it. The moment has power, in part, to the degree that we are able to see the woman as a real person enduring a real as well as a metaphoric trial. (Climenhaga, 2009, p. 87)

Performer authenticity in this work looked to activate audience empathy with performers as an engagement device. However, for dance artists with established movement vocabularies, shifting performer qualities away from the virtuosic can be problematic. As one dancer I interviewed for this project said: ‘It’s hard to be sad or happy or even real when you’re doing an attitude turn’ (Focus Group: Performer Authenticity, personal communication, March 1, 2009).

The rest of this scale encompasses a variety of possibilities for dancers which include: an ‘embodied dancer’; performing pedestrian tasks on stage; presenting entirely ‘untrained’ dancers on stage; 20 or a combination of virtuosity, embodied movement and pedestrian tasks in a single work. In this scale the traditional presentation paradigm is not necessarily on the far left but may sit somewhere closer to the middle, depending on the intention of the choreographer.

The scales in choreographic practice

As both a creator and an audience member, I wonder whether we as dance artists sometimes forget about our audience in the moment of creation. In past centuries when performance was constructed ‘for the people’, audiences felt they owned the works on stage, which were a vital form of communication and understanding in their societies. Sixteenth-century audiences often sat on stage with the performers and booed them off the stage (to be replaced by another actor) if they were not deemed acceptable.

But simply deconstructing the established paradigm is not enough. Artists need to find pathways of connection with their audiences that actively construct new paradigms, frameworks and processes. This paper presents a very brief overview of ongoing research and includes scales that have been tested in the field for over ten years. It challenges how we traditionally present dance—offering new possibilities for dance makers to make active choices regarding their audience, and proposes that innovation need not only be in the content but can also be in the presentation formats of dance.

References

- Adshead, J. (1981). The study of dance. London: Dance Books.

- Australia Council for the Arts. (2004). Resourcing Dance: An analysis of the subsidised Australian dance sector. Sydney: Australia Council.

- Australia Dancing. (n.d.). Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre (1976–ca. 1998). Canberra: National Library of Australia. Archived 26 June 2012 and retrieved from: http://nla.gov.au/nla.arc-35285

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1994). Cultural trends in Australia: A statistical overview, 1994.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1997). Cultural trends in Australia: A statistical overview, 1997.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2004). Arts and culture in Australia: A statistical overview 2004.

- Banes, S. (1987). Terpsichore in sneakers: Post-modern dance. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Bangarra. (n.d.). Bangarra Dance Theatre. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- Boal, A. (2006). The Aesthetics of the oppressed. (A. Jackson, Trans.). Georgetown: Routledge.

- Brown, S., Martinez, M. J., & Parsons, L. M. (2006). The neural basis of human dance. Cerebral Cortex, 16 (8), 1157–1167.

- Calvo-Merino, B., Glaser, D. E., Grèzes, J., Passingham, R. E., & Haggard, P. (2005). Action observation and acquired motor skills: An fMRI study with expert dancers. Cerebral Cortex, 15 (8), 1243.

- Camurria, A., Lagerlöfb, I., & Volpe, G. (2003). Recognizing emotion from dance movement: comparison of spectator recognition and automated techniques. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 59(1).

- Climenhaga, R. (2009). Pina Bausch. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cross, E. S., Hamilton, A. F. d. C., Kraemer, D. J. M., Kelley, W. M., & Grafton, S. T. (2009). Dissociable substrates for body motion and physical experience in the human action observation network. European Journal of Neuroscience, 30 (7), 1383–1392.

- Diamond, E. (1997). Unmaking mimesis: essays on feminism and theater. London: Routledge.

- Dyson, C. (1994). The Ausdance guide to Australian dance companies 1994 (1st ed.). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Dyson, C. (1 March 2009). [Focus Group: Performer Authenticity].

- Fiske, J., & Jenkins, H. (2011). Introduction to communication studies. New York, London: Routledge.

- Goldberg, R. (1979). Performance: live art 1909 to the present. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Goldberg, R. (1988). Performance Art: From Futurism to the present (2nd ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Gray, C., & Malins, J. (2004). Visualizing research: a guide to the research process in art and design. Burlington, VT, Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate.

- Haseman, B., & Mafe, D. (2009). Acquiring know-how: Research training for practice-led researchers. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology.

- Hill, L. H. (2006). (Dis)placing the senses: introduction. In L. Hill & H. Paris (Eds.), Performance and place (pp. 275). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kattwinkel, S. (2003). Introduction. In S. Kattwinkel (Ed.), Audience participation–Essays on inclusion in performance (pp. ix-xviii). Westport CT, USA: Praeger Publishers.

- Lehmann, H.-T. (2006). Postdramatic theatre. (K. Jürs-Munby, Trans.). London: Routledge.

- Levinas, E. (2003b). Humanism of the Other. (N. Poller, Trans.). Illinois: University of Illinois.

- Madden, C. (2000). Planning for the future: Statistical profile: Dance. Sydney: Australia Council for the Arts.

- McAuley, G. (1999). Space in performance: Making meaning in the theatre. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- McCarthy, R., Blackwell, A., DeLahunta, S., Wing, A., Hollands, K., Barnard, P. & Marcel, A. (2006). Bodies meet minds: Choreography and cognition. Leonardo, 39 (5), 475–477.

- Miller, L. (2005). Creating pathways–an Indigenous dance forum: overview. Dance Forum, 15 (4), 28.

- Monk, M. (1997a). Mission Statement 1983, Revised 1996. In D. Jowitt (Ed.), Art + Performance: Meredith Monk (p. 17). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Monk, M. (1997b). Process notes on Portable, May 10, 1966. In D. Jowitt (Ed.), Art + Performance: Meredith Monk (pp. 18-22). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Moya, C. J. (1990). The philosophy of action—An introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Oddey, A., & White, C. (2009). Introduction. In A. Oddey & C. White (Eds.), Modes of spectating (p. 265). Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Phillips, M., Stock, C., & Vincs, K. (2009). Dancing between diversity and consistency: Refining assessment in postgraduate degrees in dance. Sydney: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

- Scarpetta, G. (1997). Meredith Monk, Voyage to the limits of the voice. In D. Jowitt (Ed.), Art + performance: Meredith Monk (pp. 94-96). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Stevens, C. J., Schubert, E., Morris, R. H., Frear, M., Chen, J., Healey, S., & Hansen, S. (2009). Cognition and the temporal arts: Investigating audience response to dance using PDAs that record continuous data during live performance. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 67(9), 800.

- Turner, V. (1988). The Anthropology of Performance (2nd ed.). New York: PAJ Publications.

This article has not been published, submitted, or accepted for publication elsewhere.

© 2015, Clare Dyson