Old theatres smuggle their working life-blood into corridors, pint-sized rooms and studios in the shell covering the main house. Architecturally, everything is compressed, buckled even, around its central performance function and, yet, arriving in the West Australian Ballet’s diminutive home in the casements of His Majesty’s Theatre, there is a largesse of spirit at work.

Dancers burst through the confinement, negotiating corners with ease and office staff greet visitors affably. You sense that there is a determined pulse running through the place, wired to a mutual and expansive purpose, one that denies limitation.

I’ve come to interview the current artistic director, Ted Brandsen, who over the past four years has given the company more than one shot of vibrancy, before he moves back to Europe and the next episode of his story. Agile and alert, Brandsen radiates continental charm, his relaxed generosity in human relations indicating that he is the likely generator of the pervasive pulse in this wing of the building. (Maggi Phillips)

Ted Brandsen, Artistic Director West Australian Ballet 1998 – 2001.

Ted Brandsen, Artistic Director West Australian Ballet 1998 – 2001.I’m interested in factors that brought this Dutchman to Australia so I ask him how his career in dance began. “Ah well, that’s a long story … I’m a late starter.” Like in many other moments during the recollection of events, humour illuminates his features.

He completed high school in Holland and then ventured on an exchange scholarship to Hamilton College in the United States, studying history, computer science and drama. The intention was to continue with a degree in social sciences back in Holland after the exchange.

In the States however, a friend introduced him to dance classes—he was twenty years old at the time—and within weeks, he had gained a part in a local musical. Similar performances and dance classes continued until eventually it dawned on him that dance was what he wanted to do with his life.

This ‘revelation’ occurred in the face of his teacher’s warning that though he possessed ability for such a profession, he was a ‘late starter’ and, therefore, had no time to lose. In his excitement at the realisation, he rang his parents. “My father told me in no uncertain terms to call back the next day—it was 4am!” But the urgency implicit in the decision was not so easily deterred.

Back in Holland, he was accepted into Amsterdam's Scarpino Ballet School where he attended all possible classes from 8.30am to 8pm, bent on capitalising on each and every passing moment. Almost immediately following that edict of no time to waste, he began to audition, firstly for the Dutch National Ballet and then for various companies around Germany and Switzerland. Nothing eventuated.

Then at the school performance at the end of his first year in 1981, the head of the school introduced him to the director of the Dutch National Ballet, Rudi van Dantzig, who promptly offered him a job. This proposal occurred on Friday evening and “on Monday morning I was there at company class, struggling to keep my body up to the standard of the others”. After much perseverance, he became integrated into the company as a dancer.

The late starter had caught up but his appetite for sprinting towards other goals was far from satisfied. A few years later, together with two other company members, Brandsen became interested in setting up choreographic workshops. The process to convince their fellow dancers of the value of working extra hours was tortuous but the three innovators pressed on, convinced of the benefits to be gained from experimenting outside the official company artistic structure.

So it was that in 1985, Brandsen created his first work, Four Sections, to a Steve Reich composition of the same name, shaping movement patterns on Reich’s interplay between isolated instrumental sections of strings, woodwinds and brass and their loping interactions. The enthusiasm of dancers and audiences alike and the diverse movement styles generated by the choreographic workshops prompted the company to incorporate the development process within its annual program.

As a consequence of his emerging leadership skills, he was asked to remount Carolyn Carlson's Shamrock and Maguy Marin called upon him to be rehearsal director for the reconstruction of her original work for the company, Groosland. Together with the workshops, these experiences fostered Brandsen’s increasing preoccupation with choreography and soon commissions from small companies around Europe began to take him away from the company till he was spending at least half of the year in choreographic pursuits.

In 1991, he took the plunge and became a freelance choreographer. He remembers the next six years as an era of accelerated learning, even though for most of the time as he travelled across Europe and the States, he only just managed to keep himself afloat financially.

At the stage when the incessant travel was growing too punishing and ideas were being entertained of emptying suitcases and settling down with a stable group of dancers, he was short-listed for the position as artistic director of the West Australian Ballet. Knowing virtually nothing about Australia but definitely preened for taking on the next challenge to come his way, Brandsen adopted the ‘why not’ approach, flying out to Perth and Adelaide to meet up with the out-going director, Barry Moreland, the dancers and the administration.

The standard of the dancers came as a pleasant surprise and Perth appealed, so negotiating the various commitments still left to be fulfilled in Europe and the appointment of long-time colleague and choreologist, Judy Maelor-Thomas, Brandsen accepted the reins of Australia’s longest-standing ballet company.

Due to Maelor-Thomas’s appointment as rehearsal director, the creative unit that had been developing around Brandsen over the previous years became incorporated into the company’s changing image when Brandsen took up the position in 1998. Together with choreographer and trusted choreologist, their respective partners in turn provided lighting, décor and costume design, creating illumination and colour consistent with the refined twists and passions of the movement.

Brandsen’s vision for expanding the company’s repertoire arose from considerations of the size and circumstance of the company. Due to the relatively small number of dancers, reconstructions of the major classics were prohibitive and, besides, what the company needed was a unique identity not just in the Western Australian context but in a national, if not an international sense.

Brandsen thus developed a policy of initiating full length works tailored to the company, like Chrissie Parrott’s ‘retro’ Coppélia and Brandsen’s stream-lined Romeo and Juliet, enhanced by regular programs of short works by a range of choreographers from Hans van Manen, Stephen Page, Gideon Obarzarnek, Natalie Weir and Simone Clifford.

At the same time, Brandsen reinstituted annual choreographic workshops in the Western Australian environment, encouraging the dancers to experiment with ideas and styles in the supportive studio environment. In 2001, nine out of the sixteen dancers voted to create new works which Brandsen acknowledges is a fantastic percentage for a company generated from classical ballet principles.

He also invited local choreographers to contribute to the choreographic explorations, conscious that the experience of people like Stefan Karlsson, Margrete Helgeby and Jon Burrt can challenge the dancers’ range of skills.

Another significant element in Brandsen’s approach to the company was to establish a rapport with the company members, encouraging a sense of ownership within each individual so that the group had a shared stake in the company’s ventures and successes. Maelor-Thomas and Brandsen had often discussed how they would run a company, sensitive to the way in which “many artistic directors forgot where they came from five minutes after being appointed to the privileged position”.

Brandsen is emphatic about the necessity to appreciate the dancers’ perspectives, nurturing their ambitions while warding off debilitating factors like exhaustion and self-doubt. The group’s heterogeneity is another factor that Brandsen views as integral to a company’s well-being, noting that Errol Pickford is a ‘Pom’, Askhat Galiamov is Russian and Emeliana Lione is Italian.

Youthfulness and experience mix into and enrich the cultural diversity. At the same time, he detects a certain parochialism within the Australian mentality that obstructs the internationalism enjoyed by European companies:

It’s fine for Aussies to gain employment overseas but I strike trouble when I try to employ the best dancers from Europe for WA. A union official intervened when I brought Hans Van Manen out to mount Five Tangos. His blunt reasoning was that “there were plenty of choreographers here mate!”

Fortunately, Brandsen won the case for van Manen and intermarriage and immigration provide, to a certain degree, a stimulating, ready-made cultural mix of personalities.

Promotion also figured prominently in Brandsen’s plan of attack for the company. Given the Australian affinity with extrovert physicality, Brandsen struck on a sport’s formula, highlighting the dancers’ corporeal prowess with an unabashed ‘sexy’ edge for both the men and the women. Gone are the images of ethereal women and effeminate men! A TV campaign complete with company jingle has been instrumental in filtering the new company image through to the community.

Here, Brandsen aimed for visibility in a company too often accused of operating behind closed doors. One of the significant strategies to profile the company comes by way of its educational programs. Early in Brandsen’s residency, an education officer was appointed to conceive and conduct special programs to make the art form accessible to young people. In liaison with Perth schools, pre-performance workshops, talks and follow-up sessions are conducted to inform the students about the works viewed and to provide a channel for airing enthusiastic reactions.

Brandsen is proud of responses like that recently received from a teacher who claimed that a book of writings and illustrations produced after the company’s performances yielded the richest feedback generated by the students from any extra-curricula activity.

Further initiatives, like Jump Start! where disadvantaged children are sponsored to attend the company’s dress rehearsals, add to Brandsen’s achievements in fostering young people’s identification with the company and building a future audience for dance.

Brandsen is also clear that touring is a crucial part of the company’s activities, not only to disseminate programs across the state’s regions and increase the economic viability of the company’s typical ‘new works’ seasons but also to make a cultural statement in the national scene. The tour to the eastern states in 2000 was a huge success, confirming Brandsen’s perception of the company as an alternative to the Australian Ballet. He firmly believes that further investment to cover the somewhat exorbitant costs of transporting even such a small company across Australia’s vast distances is imperative if the company is to acquire some form of artistic and financial stability in the long term.

Once the company is able to establish an identifiably discrete identity, overseas touring via the festival circuit should be able to fully exploit the company’s carefully developed repertoire. At the moment, their profile is not sufficiently distinctive to attract the attention of Perth’s arts-affluent neighbour, Singapore, but Brandsen is confident that this perception will change. “Recognition”, he adds, “by way of last year’s choreographic award for my version of Carmen is a step in the right direction”.

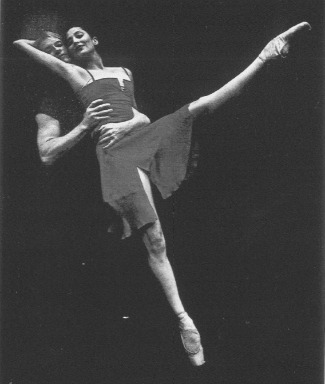

Benazir Hussain & Daryl Berandwood in Ted Brandsen's production of Carmen for West Australian Ballet, 1999. Courtesy WAB. Photo: Ashley de Prazer.

Benazir Hussain & Daryl Berandwood in Ted Brandsen's production of Carmen for West Australian Ballet, 1999. Courtesy WAB. Photo: Ashley de Prazer.Touring raises the constantly vexed issue of funding. Brandsen’s frustration with the disinterest of politicians and bureaucrats is not veiled. He acknowledges the incremental increase of funding recommended in the Nugent Report but quickly warns that suggestions of merging the opera and ballet will just not work since the two disciplines pursue parallel but distinct philosophies that entail specific strategies and programs. “The arts in this country are peripheral in contrast to Europe where they are perceived as the centre of the society”.

Brandsen cites the relative funding figures (for dance) between Europe and Australia as not simply a question of demographic inequity. The 80 percent average government support for companies in Europe is bolstered by a small 1 – 3 percent from private sponsorship with the shortfall, up to 20 percent, secured through box office.

In contrast, Australian companies acquire an average of 60 percent of their budget from government funding agencies and struggle to sustain themselves, chasing the deficit through elusive sponsorship deals and box office takings from a relatively low population base. “Even Britain is coming into line with continental Europe with Blair’s new policy for the arts”, he adds as if to point to a peculiarly Anglo-Saxon reserve with respect to cultural matters.

Ideas about investment in the arts prompts a Brandsen analogy: “If you want a healthy, vital and muscular body, then you feed the man well. If you just throw him the crumbs, how can he grow?” The present tight financial climate aggravates him even more considering the successes of 2000 with the tour, awards, and the national telecast of Chrissie Parrott’s Coppélia. “What more evidence do they want of the company’s viability?”

In spite of Brandsen’s recognition of creative time lost in the pursuit of sponsorship, he voices a positive note about future cultural development in this country for he believes that the private sector’s credits will result in national and local identification with the company and its endeavours. When asked if there are factors to offset the depressing funding situation experienced in relation to the valued position of the arts in Europe, Brandsen’s reply is prompt:

Here, companies are not bound down by tradition and its subsequent red-tape that are detrimental to innovation. I have confidence that, in this country, I can initiate and be supported in making changes aimed to enhance the company. In Europe change tends to be viewed with suspicion.

Paradoxically, adverse financial conditions enable greater creative freedom. In this respect, he is highly appreciative of the administrative arm of the company. The board of management has supported him every inch of the way and the executive director, Louise Howden-Smith, “has been fantastic, contributing huge initiatives on her own behalf”.

The future for Brandsen after WAB is replete with honour and challenge. He could not refuse the offer to return to the Dutch National Ballet as associate director alongside the current director, Wayne Eagling, formerly of the Royal Ballet.

So in 2002, Brandsen will return to the home company to be responsible for its contemporary neo-classical repertoire, guest choreographers and reconstructions and thereby secure his place alongside his cherished icons, Rudi van Dantzig, Hans van Manen and Toer van Schayk.

Size too sparkles in his eyes since, as Holland’s largest company, some eighty dancers are employed to work on stages that would gobble up His Majesty’s. With space-eater instincts, he is looking forward to the prospect of creating new works that, like his initial Four Sections, propels dancers out into the musical flow of space. As much as he has appreciated the atmosphere of His Maj, “its nineteenth-century stage was not conceived for the athleticism of dance in the twenty-first century”.

One endearing quality in the late starter’s next move is his comprehension of the accumulative depth that experience entails. While the injunction that the WAB “better bring me back to mount work” is flippant and by no means written in stone, the remark suggests that ties made in the past will be knitted firmly into the future. I suspect that we will see more of this man who refuses to let time get the better of him.