How is performance ‘viewed’, ‘witnessed’ and ‘experienced’? What elements of a performance can be changed to vary audience experience? How can we re-engage the audience as an active participant in the creation of meaning? Is it possible to disengage the proscenium arch as a mechanism of passive viewing and re-define the theatre as a place of dialogue between audience and performance?

The 19th Century legacy of a ‘passive’ audience, which is standard in most contemporary theatres and supported by the ‘traditional presentation paradigm’, involves performance that is usually made to be ‘received’ by a seated audience, who are in the dark, front facing with restricted or no agency. ‘Passive’ in this context, refers to this monologic ‘receiving’, as well as limited physical and active choices available to the audience: ‘The spectator is generally relegated to ‘receiver’ status, having little impact on process of performance except in standard, structured response’ (Kattwinkel, 2003, p. ix). Wilhelm Dilthey who wrote extensively about the lived-experience remarks that ‘one cannot “think” a poem. One experiences it with all one's faculties’ (in Fehling, 1943, pp. 15 – 16). But within the Western presentation paradigm, experiencing dance ‘with all one’s faculties’, is near impossible.

This research examines the traditional Western presentation model of ‘passive’ viewing and offers alternatives for choreographers to create experiential performance which centres around an active dialogue with their audience.

The traditional presentation paradigm

It could be argued that most contemporary dance works throughout the world, are currently created for, and then presented within, the traditional presentation dance paradigm: seated or fixed ‘passive’ audience, a proscenium/single front theatre with a separation between audience and performer, limited or no audience agency, 60 – 90 minutes in length and created tour-ready for equivalent theatrical architecture of this paradigm.

While every country creates culturally specific dance, ‘contemporary dance’ (even with culturally specific vocabulary, thematic or content), is often made without questioning this traditional Western ‘presentation paradigm’, which does not privilege the experiential, or the audience, except from a single viewing point. While many choreographers from non-Western countries who are creating work within that paradigm (with similar vocabularies, conventions and presentation format), localise their work with geographic and cultural concerns outside that framework, these artists usually create and then present work within this established paradigm—so while the movement and content may vary, the way in which the audience engages with it does not.

For example, Indigenous choreographers in Australia working in a contemporary context are creating works with specific cultural concerns and innovative choreography drawing on their specific history of dance, but they are, more often than not, creating the works to be presented within the Western traditional presentational paradigm.

But what happens when elements of this widely accepted traditional presentation paradigm are changed to privilege the audience’s engagement with the work?

Performance works that challenge this established presentation paradigm and privileges a dialogue with audience, allow the concept of the work to reveal to the artist how best the audience can experience it. This then informs how content can be generated: Will the audience understand the concept of choice if they have choice? Will the audience remember childhood fun if they play on swings during the performance? Will an audience understand that they are voyeurs if they watch through peepholes? This research looks at how changes in the Western presentational paradigm alter how audiences engage with dance. Along with the tools of audience agency, liminality, variations of site, ritual and audience proximity—tools that that challenge the traditional presentation paradigm and create engagement via physical interactions with the audience—the current question for this paper is: can ‘performer authenticity’ also be used as a tool of connection with the audience?

Audience engagement tools – why do we want to engage more?

Heidegger (in Guignon, 1983, pp. 132 – 138) talks of experience and says that as Dasein (nature of Being) we have two potentials: one that is situated in the world of social constructs and constraints (work, domestic, children etc.) that require us to perform socially constructed functions where ‘we must draw a horizon around ourselves in order to be able to focus on our daily affairs’ blinding us to our ‘ownmost possibility’; and the other is situated in the knowledge that our lives are finite—that we will die and once we live in that knowledge (Being-toward-the-end), then we then have active choices about what we will do with our lives. The Authentic self is one that is Being-in-the world, but particular to the world—one that makes decisions (or non-decisions) about how he will go forward towards his death (ibid).

While these philosophical views situate the authentic within our daily lives, what ramifications do they have within the constructed world of performance? When an audience are engaged within an active dialogic, there is an artistic responsibility to create an environment (and an experience), which allows the audience to Be-in-the-world, even if it is only for the duration of the performance.

When exploring the role of the performer as an engagement tool, Fraleigh reminds us that "my dance cannot exist without me: I exist my dance" (Fraleigh, 1987, p. xvi). While the focus in this research is on audience, looking at ‘authenticity’ in dance may also be an opportunity for the dancers to reveal themselves as authentic, opening up possibilities for the performer that are not usually part of the traditional dance paradigm. It is this paradigm shift that I propose could be used to facilitate the audience's Being-in-the-world for the duration of the performance event.

Authenticity in performance

When a work is specifically designed to be experienced by the audience, then the role of the performer, the actual performance, changes the experiential possibilities for that audience. With historical precedents in theatre and post-modern dance, the ‘real’ or ‘authentic’ dancer is a performer who is able to connect via immediacy, engaging their audience not by illusion, but through a visceral connection of the everyday.

Authenticity, when connected with dance, connotes a long history of therapeutic usage. ‘Authentic Movement’ and ‘dance therapy’ are established processes by which the individual embodies movement as therapy, utilises these processes as a witnessing and teaching tool, or as a process of engagement with the self and the consciousness within the body (Whitehouse, Adler, & Chodorow, 2005, pp. 11 – 12 and 142 – 149). While the processes of Authentic Movement and dance therapy have wide reaching appeal and can have a profound impact on the individual mover (whether they be dancers or not), these processes have little connection to authenticity within the presentation paradigm of theatrical dance.

What word then, to use when talking about ideas of authenticity in performance?

Dance artists who work with improvisation are often required, as part of this form, to be in-the-moment or authentic when they perform. In discussing performer authenticity, Andrew Morrish, 1 one of Australia’s leading dance improvisers, thinks that performers are always authentic if they are working within a relational paradigm: I’m in relation to you as the audience and once I acknowledge that, anything I do is authentic. In terms of his improvisational form, he prefers the word ‘present’ to ‘authentic’ as there is less judgement. What I’m interested in however, is how audiences feel about that: do audiences engage more if they perceive a dancer is being present, authentic or real?

Being There

This was an initial research question during the development of a new contemporary dance work titled Being There (2007). Audience feedback 2 from this work said that the performers’ realness made them engage with the dancers more: "We really felt them fall and cry and hurt themselves". Other feedback supported this: it was suggested that when the performers spoke text they didn’t write, the connection was broken—because "they weren’t as believable as when they were just being themselves". In other words, they were not authentic.

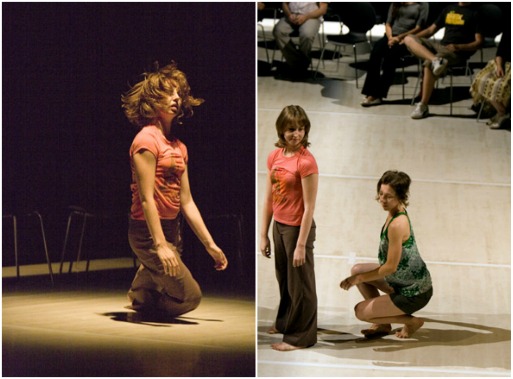

Being There. Performers: Emily Amisano and Trish Wood. Photo: Fiona Cullen

Being There. Performers: Emily Amisano and Trish Wood. Photo: Fiona CullenMathew Reason’s writing about theatre audience reveals that while performer authenticity might be unusual in dance, it is a standard way for audience to connect with actors within theatre. Reason ran a small focus group looking at ‘liveness’ and observed that implicit in his focus groups’ answers about the actors was that:

‘the speakers conflate “good” and “like” with “believable” and “bad” or “dislike” with “unbelievable”. Two examples make this relationship clear:

Roger – I thought she was really believable, really good.

Elizabeth – I thought he was very good, very believableThe speakers not only apply these assessments to the performers, but to the production as a whole, where something either feels “right” or is “not convincing”.’ (Reason, 2004)

What has to be acknowledged when looking at this area, is that however real or authentic a performer is at any given moment on stage, she is still on stage and within a constructed environment. Dance works are not performance art: the paradigm is different. In dance there isn’t an assumption that the dancer is the work of art herself, even if it is a solo. Rather, that she is revealing the work of art and is part of the work of art.

But the edges of what is possible in every art form can be blurred. Dance researcher and theorist Ryod Climenhaga believes that when there is a blurring of the dancer’s role within dance, then that process can be one of connection for the audience. To support this, he cites Pina Bausch’s work, saying that her attention to performer authenticity creates "a world of immediate presence that directly engages the audience, rather than a re-presented world that comes from a constructed idea of time and space" (Climenhaga, 2009, p. 100).

Why do we value authenticity?

Heidegger's use of the word authentic "brings with it a more sharply defined sense of what it is to be human" (in Guignon, 1983, p. 136). He suggests that as an authentic, transparent self, we know ourselves, our social requirements, our finite time as a living being and the impact of choice on our life. All of our decisions, once seen and taken responsibility for, are what make us authentic: make us ‘be-in-the-world’. It is that understanding which makes us unique. We now have choice. This pathway of transparency and authenticity, ‘as the “art of existing” points to a capacity for grasping life in a different way’ (in Guignon, 1983, p. 136).

The assumption here, however, is that to Be-in-the-world, is better than being inauthentic and that authenticity and experiencing are nourishing ways not only of living, but also of engaging with live art. Anthropologist Charles Lindholm says that while this search for authenticity is a current concern, it has been active since the 18th Century and that ‘the quest for authenticity touches and transforms a vast range of human experience today… authentic art, authentic music, authentic food, authentic dance, authentic people….’ (Lindholm, 2008, p. 1).

But where has this desire for authenticity come from?

The breakup of feudal relationships in 16th century Europe changed established societal positions and brought into question an individual’s sincerity and broader issues of authenticity (Lindholm, 2008, p. 3). By the late 18th century, Rousseau’s Confessions (Rousseau, 1953) had been published, shockingly revealing his ‘true’ person, and in the process becoming the "harbinger of a new ideal in which exploring and revealing one's essential nature was taken as an absolute good, even if this meant flying in the face of the moral standards of society."’ This attitude, according to Rousseau, was about "directly experiencing authentic feeling. Only then could a person be said to have a real existence," (in Lindholm, 2008, p. 8), which is central to the contemporary quest for authenticity.

But does our desire for authentic experiences in society include a desire for it within the arts?

The real dancing body

Classical ballet and Western contemporary dance are art forms that are taught on the body. Separating the self from the body allows the body to be trained more easily: changes, criticisms and discussions are about the body and its facility or limitation and not about the person. The student is taught this from a very young age. Invariably there is a student to whom this has not been made clear and she is, usually in her teens, devastated by criticism that challenges her self worth. This is a high drop out age for young dancers.

But those who continue eventually find ways (some successfully) to hear discussion and criticism of their bodies, their body's movement and their performance skills, as "part of the job" and not as a personal attack. It seems that those who survive most successfully in this industry have professional skills in detachment and in leaving the personal and the emotional out of the studio. Even when asked to bring these elements into the studio, this requires maturity and additional skills from both the performer and the creator, skills that are not inherently part of dance training.

When a dancer is asked to 'be herself' on stage, what does that mean? And how does she go about looking at this question? Her training, often from the age of six, has been designed to train her body as an instrument and to separate herself from that process, although not entirely—choreographers still want 'emotion' or sometimes 'rawness' or, in rare cases, 'reality'. But what they are asking for is a pre-conceived construct of these things or for a dancer to draw on real life to expand a character—much like an actor might. If they had really wanted those things on stage the choreographer could have worked with an untrained performer, entirely removing the virtuosic training and its resultant ‘performance’. As one dancer said to me: "it’s hard to be ‘angry’ or ‘sad’ when you are doing an attitude turn." 3

The dance profession has embedded within it not only conventions of how to perform, but how to teach, create and also how to watch dance: audiences expect that a 'dancer' will 'dance'. The question of authenticity is most often discussed in terms of interpretation: "She dances that role so well, she is so believable...." But the question of her authenticity is shrouded in the expectations of the profession. There is no discussion of her authenticity in terms of who she is as a person, unless she is a dancer first, and then a person. The assumption is that "the skills, intuition, and genius of the interpreter were all that was necessary to present a piece with authenticity and conviction" (Lindholm, 2008, p. 26).

Leading Australian choreographer Meryl Tankard auditioned for Bausch’s company while on tour as a member of The Australian Ballet. She recounts her audition process: "It was the first time a director had encouraged me to project my own personality on the stage, and it opened a whole new world. I had nothing against being a sylph in a tutu and toe-shoes, but the whole classical repertory suddenly seemed like a museum" (in Climenhaga, 2009, pp. 13 – 14).

What do performers think?

Gadamer reminds us that the "question of how truth is revealed or disclosed by art also suggest how art conceals and hides truth" (Gadamer, 2003, p. 141).

Andrew Morrish’s[See previous note about Morrish.]] form is improvisation and because he is constantly required to be in-the-moment or authentic, he is an excellent person with whom to discuss ideas of performer authenticity. Morrish says that one of his expectations of himself as an experienced performer is ‘to walk in front of the audience and say: ”We’ve all just arrived and this is the only chance we’ll have to have this moment”. As if there is no tomorrow. I’m trying to give myself that much courage and that much permission to be who I have to be in that moment’ (Morrish, personal interview, Paris, 2008).

But Morrish doesn’t believe that a performer, no matter what they do, can be inauthentic. This is contrary to my belief that authenticity is something different to ‘performing’ and because of that difference, it could be utilised as a tool for engagement. Morrish says of his own practice that he doesn’t know how to be inauthentic and doesn’t use the terminology because ‘authentic’ "implies that there is something deep, and something superficial (on top) and it creates a separateness" (Morrish, personal interview, Paris, 2008) and judgement of performers. The form of improvisation, however, is one that requires a performer to ‘be-in-the-moment’ because material is not pre-made. What do dancers, who work in environments where a performance is set and have seasons of up to several weeks, think of performer authenticity?

I undertook a focus group to ask dancers this very question. The group consisted of five professional dancers who have been working in a variety of large to medium dance companies 4 for their entire professional lives. These dancers represent the established core of the profession: they have worked with numerous innovative and avant-garde choreographers, but they have done so within company structures. This means they were usually on full time contracts, were expected to be at the height of their profession, have toured nationally and internationally and have an intimate knowledge of choreography, performing and performance.

The focus group came together informally to discuss ideas of performer-presence and authenticity in their profession. The general consensus of the discussion was that as professional ballet and contemporary dancers, part of their profession was to "be whatever was required" by the choreographer. In other words, as dancers, their job was to be great technicians but also to embody whatever ideas, personas or characters the choreographer wanted. This wasn’t considered a positive or a negative aspect of their job, but one that was required in all professional situations they had worked in.

George 5 , 43, spent 17 years dancing professionally and questioned what authenticity was in this context and whether ‘dancing’ is now part of that, saying that after dancing since he was six, ‘authenticity’ on stage would require a level of ‘de-coding’ of the body. "And if that’s what you want" he added, "then why use dancers at all? Why not use untrained people on stage?"

Christian, 39, said that "our profession is about getting away from yourself—about being able to leave some things out of the studio", which involves a series of professional skills that are learned over time and not easily shed. In his 19 years working as a professional dancer he said that he was only ever asked to ‘be himself’ once on stage, by an independent artist and never while he was working in a main-house company, but that the choreographer only asked for it while he was doing a pedestrian task. 6

David, 36, with 16 years dancing professionally said that "it actually really depends on the choreographer and what they think is authentic. They can see something you do and believe it’s authentic or ask to you to change something to fit their version of authentic." Tony added to this by saying that "if you are presenting something in a proscenium arch—how can it ever be authentic?" because you are presenting it in a ‘performance’ paradigm and repeating it each night.

When I asked the focus group what would happen if they were required ‘just to be themselves’ on stage, Mimi said that if she were asked to be herself on stage then ‘you’d still be an actor—you’d be clever and work out what bit of you works.’ David agreed saying that ‘you can certainly act being authentic.’

While philosophically, Morrish’s responses are different to those from my focus group, what all the performers suggested is that they are rarely required to ‘be authentic’ when they are onstage because it isn’t traditionally part of the profession unless it’s improvised. If a performer is required to be authentic on stage, it’s an inversion of an established performance code and one that often unsettles an audience into a different kind of interaction with the form:

Bausch is not the first to engage this type of presentation and expression, but she is the first to place that bodily presence at the centre of her presentational praxis. Rather than for a constructed present, the performer is present, and that presence both creates and addresses our own sense of self intertwined with others. Our own connection to the world is shown as a bodily process, necessarily fractured, but what is important is not so much the gaps created between ourselves and others, but the persistence with which we try to bridge those gaps. (Climenhaga, 2009, p. 67)

Does performer authenticity make audience engage more?

While Morrish believes that everything on stage is authentic, he does feel that there are elements of "being in the moment" that change how an audience connects with you. He also acknowledges that when an audience knows that what you are doing is ‘real’, they connect more:

You are in survival mode and that’s what we do when we perform. It doesn’t get more authentic or honest than that. It’s also clear that audiences love that. This honesty thing is part of this too. Sometimes people are very disappointed if they feel that the performer is pretending… You can’t be dishonest as a performer. You can pretend and cheat as much as you like and the audience sees you pretending and cheating. They know you are a pretender and a cheater. It’s always authentic in that sense, in that survival paradigm. (Morrish, personal interview, Paris, 2008, p.24)

The difference between authenticity and inauthenticity "lies not in what possibilities are available, then, but in how those possibilities are heard and taken up" (Guignon, 1983, p. 140). According to Bausch, she utilises these tools because they are interesting to audiences, which infers they are being used as a tools for engagement—and consciously at that.

What do audiences think?

As early as 1908 ads for Coke earnestly exhorted consumers to "get the genuine." This is only one example of manufacturers’ efforts to persuade buyers that their brand was more natural, more located in history, or more pure, or more real, that anything their competitors had to offer. (Lindholm, 2008, pp. 55 – 56)

But does this translate to audiences or consumers of contemporary dance? Bruce’s answer, one of the participants of a recent audience focus group, 7 was an unequivocal Yes: "Of course if I see someone on stage really telling their story I will connect with them more." But his assertion was that it would have to be really ‘real’ and not a constructed real. A point, he said, that made a difference.

As Lindholm points out, "If a Rembrandt can " (Lindholm, 2008, p. 1). In the case of performance, the ‘experts’ become the audience, and if they believe a performer is being authentic then their experience of her is different. Allain and Harvie take this assertion further by saying that the "performer's presences strongly engages the audience's attention and cultivates the audience’s own sense of presence—a sense of the importance of being in the moment at that event" (Allain & Harvie, 2006, p. 193).

Engagement, proximity, authenticity

After each of my performances I ask for feedback about audience experience. The questions for Being There (2007) were about audience proximity to the dancers, and there was a specific question about whether the performance quality/authenticity of the performers made the work more engaging. The majority of the feedback said that the authenticity of the performers engaged them in unexpected ways:

‘With the intensity of the performers I couldn't help but be engaged.’ ‘The emotional honesty of the dancers drew me in.’ ‘It broke my heart’ ‘The dancers’ performance quality—particularly their ability to cross performance genres was far more engaging that any work I've seen.’ [She] ‘drew me in with her groundedness and the “genuineness” of her emotion.’

What is interesting to note about the reactions to these particular performers, in this particular work, is that the ‘engaged’ responses 8 were centred around the audiences’ proximity to the dancers: the audience was asked to sit in an ellipse on stage and the dancers were often performing quite close to them. While the audience didn’t move once the work began, the proximity to the dancers allowed them an unusual opportunity to see these dancers deconstructing their own profession and their own world of performance in an intimate environment. This was done for, and with, the audience, and for some it connected them deeply with the performers.

For Georg Simmel, an early 20th Century sociologist, "the eye of a person discloses his own soul when he seeks to uncover that of another. What occurs in this direct mutual reciprocity is the entire field of human relationships" (in Flanagan, 2004, p. 109). It seems from feedback over the last three years that audiences do engage when elements of the traditional performance paradigm are inverted or consciously manipulated by choreographers. What is interesting to observe however is, that while some inversions are gimmicks and done without thought or intent, those artists specifically wanting to engage their audiences via shifts in this paradigm, often make works that connect on profoundly experiential levels.

While in theatre or film, an audience might expect 'realism or 'authenticity' as a performance quality from the actors, in dance, this is not usually the case. Authenticity is used widely throughout society to denote ‘real’ or as in the case with Reason’s focus group, ‘better’. Used in dance, these connotations challenge traditional conventions of a distant, virtuosic dancer, and facilitate performer authenticity as a tool for choreographers to form deep connections with their audience via reality and the immediacy of live performance.

References

- Allain, P., & Harvie, J. (2006). The Routledge Companion to Theatre and Performance. London: Routledge.

- Banes, S. (1987). Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Climenhaga, R. (2009). Pina Bausch. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fehling, F. L. (1943). On Understanding a Work of Art. The German Quarterly, 16(1), 13-22.

- Flanagan, K. (2004). Seen and Unseen: Visual Culture, Sociology and Theology. Bassingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fraleigh, S. H. (1987). Dance and the Lived Body. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2003). Gadamer on Heidegger: Heidegger's Later Philosophy. In D. Milne (Ed.), Modern Critical Thought (p. 12). Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Guignon, C. B. (1983). Heidegger and the problem of Knowledge. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company Inc.

- Kattwinkel, S. (2003). Introduction. In S. Kattwinkel (Ed.), Audience Participation—Essays on inclusion in performance (pp. ix-xviii). Westport CT, USA: Praeger Publishers.

- Lindholm, C. (2008). Culture and Authenticity. Malden: Blackwell.

- Reason, M. (2004). Theatre Audiences and Perceptions of 'Liveness' in Performance. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies Particip@tions Volume 1, Issue 2 (May 2004). Retrieved October 23, 2008, from http://www.participations.org/volume%201/issue%202/1_02_reason_article.htm

- Rousseau, J-J. (1953). The confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (J. M. Cohen, Trans.). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Whitehouse, M. S., Adler, J., & Chodorow, J. (2005). Authentic Movement (5th ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.