Pavlova as seen in a linocut by Enid Dickson. Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Pavlova as seen in a linocut by Enid Dickson. Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South WalesMadam, you came

With your bright eyes a-flame,

And with your slim white hands

Plucked at our heart strings, till the inmost soul

Of that huge audience was with you, whole,

And we went through

With you

The opened doorway into faery lands.There, as you danced,

We (with you all the time)

Could feel the wind blow from Olympian heights,

Could smell the sweetness of that clime,

Could see the mellow moonlight, that down glanced

Between the leaves on summer nights,

And found them dancing in the Grecian glades

– Terpsichore and her white maids,

O heavenly muse, hast thou then come again

To mortal men?Terpsichore… And yet

Was hers that elfin grace

Of limbs? And in her face

Had she that changing flight

Of quick expressions, where the gay, the glad,

The mocking, and the sad

Flash into sight

And pass

Like shadows on the grass?You are not heavenly born

Nor earthly,

But had a witch for mother on a morn

Still, cold, and grey,

And with the coming of the day

You came –

When in the east a blazing torch was set

Then leapt your spirit-flame.

For you are pale and stately as the dawn

And like the dawn you came.

Joan Wilkinson 1

The thought of the five-week sea voyage to Australia frightened Pavlova. In 1926 she finally took that journey, breaking it in South Africa, and her first Australian tour commenced in Melbourne. The company comprised approximately 45 dancers, her partners being Laurent Novikoff and Algeranoff, and even though His Majesty’s Theatre in Melbourne was the venue for the first season, which ran from 13 March to 14 April, the Sydney Daily Telegraph published a photograph of her arrival in Australia on 12 March.

Before her first performance, the firm sponsoring her Australian tour, J.C. Williamson Theatres Ltd., were uncertain what to do regarding Pavlova’s superstition about entering a theatre for the first time. They had not “yet arrived at a decision as to which one of them [would] carry Pavlova over the doorstep…” 2 Who eventually did remains a mystery.

The debut performance attracted a packed audience of over 2,000. The Fairy Doll was to be performed first. Algeranoff recalls that while climbing the steps to take up her position as the Fairy Doll, Pavlova said to him, “Perhaps they like, perhaps not, who can tell?” 3 He also recalls that friends of his in the audience told him that people were bewildered because, at first, she merely stood still: but from the time she started dancing, the success was amazing. The Melbourne Argus for 15 March concluded in its massive, enthusiastic two column review that “hers is an art not of display, but of restraint.” 4

People from far and wide attended the performances during the Melbourne season. One evening, when it came to her attention that a couple had travelled a distance of 176 miles from Deniliquin in the Riverina district of New South Wales, and another lady all the way from Hobart, a distance of 451 miles, she invited them backstage to her dressing room for tea after the performance to thank them for their interest and enthusiasm.

The final night in Melbourne surprised the company with an Australian custom, the throwing of paper streamers, which flowed from every part of the theatre. The dancers, taking their bows on the stage, were almost knee-deep in them. The success of the Melbourne season had been beyond all expectations. C.B. Westmacott, Williamson’s general manager, stated that the four-week season “returned £30,000 to the box-office; it was the most wonderful season ever experienced in the southern capital”. 5 Pavlova, however, maintained that she never measured success by box-office receipts: she chose her repertoire in order to reveal her art, and her performances were given solely to delight her audience, not to meet box-office requirements.

During her stay in Melbourne, Pavlova became familiar with another Australian custom. She made many trips to the Dandenong hills, and after one of them, the Melbourne magazine Table Talk wrote that “[she] had gone on a picnic to the hills, and had sat cross-legged, to a meal of grilled chops and Australian bush-style ‘billy tea.’” 6 Her love of nature also found her spending many hours visiting Melbourne’s botanical gardens and feeding the swans on the lake.

Australasia Films had planned to make a movie of the company while they were in Melbourne, and a number of short films were made in the grounds of Sir George Tallis’ home in Toorak. The stills were printed in newspapers and magazines. Unfortunately, however, the movie was never completed.

The next part of the tour took the company to Sydney. They left Melbourne in the early evening, all very tired. They could not go to bed because they had to change trains and carry all their own luggage across to another train in Albury, as the rail gauge changed there. This was something they were unaccustomed to and were quite surprised by. They had a huge amount of luggage, which included sets and scenery made for large theatres. They also carried 20 electric heaters, as they found the dressing rooms poorly heated, or sometimes not even heated at all.

Anna Pavlova arrives at Central Railway Station, Sydney, 16 April 1926. With her, L to R, are Laurent Novikoff, Victor Dandré, Lucien Wurmser (musical director) and John Tait of J.C. Williamson. Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Anna Pavlova arrives at Central Railway Station, Sydney, 16 April 1926. With her, L to R, are Laurent Novikoff, Victor Dandré, Lucien Wurmser (musical director) and John Tait of J.C. Williamson. Courtesy: National Library of AustraliaThey were to arrive at Sydney’s Central Railway Station on the Melbourne Express at 10.30 am on 16 April. An invitation for the public to attend a welcome reception on the platform for Pavlova and her company had been published in the Daily Telegraph that morning and next day the paper reported that a “dense crowd” (estimated by some to be about 10,000 people) had gathered at Central Station and that Pavlova was greeted with “a burst of cheering” which “assured her of a pleasant association with the new-found lovers of her art in a strange city”. 7

Among the welcoming committee were C.B. Westmacott of J.C. Williamson, a representative of the Musical Association, G. de Calros Rego, and A. Lubimoff, secretary of the Russian Society. A photograph of Pavlova’s arrival in Sydney appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on the next day. She was interviewed by a Daily Telegraph reporter in the reception room of her suite in the Hotel Australia, sitting amidst floral tributes sent to her by admirers and friends, and, while “Seated carelessly on the arm of an easy chair she talked of her art for her art’s sake.” 8

In press interviews, on every convenient occasion, she always made a point of expressing the necessity for a state or subsidised theatre. Her view was that a government mindful of the education of its people should also have in view its “cultural development, in which the theatre plays an important part”. 9

The Daily Telegraph of 17 April reported that she spoke first of Australia’s natural beauty and wonderful climate and, continuing on, using her eyes, facial expressions and gestures to emphasise her point,said,

For 150 years the Russian Government has subsidised the Imperial College, where all branches of the art are taught: and during this century the Government has expended £300,000 on similar colleges, whose influences have spread throughout the world. You have a very beautiful country here, why cannot you do something like that? Ah, but you are so young… At the schools in Russia they combine every branch in one – dancing, scene-painting, music, and dress-designing. In these colleges they work for art alone. If the Government did not help the schools could not remain open… Governments are now helping the people of other lands – America and France – and it would be good if your Governments could be induced to do so here… The difficulty with a new country is that the perfect combination of music and dance has not been presented, and it is difficult for the imagination to follow what the original schools intended. Perhaps some day the cinema will be an aid to the student… Again art cannot exist without tradition… 10

She also emphasised the necessity for correct tuition, and the fact that harm could be caused by incompetent teaching. “The schools must be properly equipped and properly controlled, otherwise students [will] become cripples instead of artists.” 11 The report then said that no time was lost after the interview, and rehearsals by the company were commenced that afternoon.

Pavlova’s manager (and possibly her husband), Victor Dandré, said that Pavlova disliked interviews. She was aware that when being interviewed she had to give diplomatic answers but was afraid of saying more than was necessary. She was a very genuine and forthright person and detested evasion. The majority of questions she usually found common and uninteresting, but was surprised at the conscientiousness of the Australian critics, who, no doubt, not having seen much ballet, must have read up on it, as well as being aware of views that she herself had expressed in the past.

Pavlova also did not like press photos, and often hid her face with her hand or a bouquet of flowers when being photographed. She did, however, commission Harold Cazneaux (who apparently considered her the world’s most beautiful woman) to photograph her backstage in Sydney.

The Sydney season opened on 17 April at Her Majesty’s Theatre (which the company seemingly found more comfortable than the Melbourne theatre) and continued until 20 May. Music incidental to a performance on 23 April was also to be broadcast by radio station 2FC, with the Australian tenor Alfred O’Shea to sing during the intervals. A program such as this had already been successfully broadcast in Melbourne.

The first night opened again with The Fairy Doll and the Daily Telegraph reported that it was “an absolute triumph” which began

n an atmosphere of tense expectation... The custom nowadays is for the theatre-goer to seek for comparisons in attesting the value of an artist. For Pavlova there can be no such test, no weighing of her skill against another, no setting off of a quality here and another there, for she is the acme of perfection … [she] stirs the imagination and conveys the impressions of light, and grace, and passion: her dancing is poetry, and music, and rhythm expressed in the technique of an absolute genius’, and, at the conclusion of the second part of the presentation, Chopiniana, the audience ‘again burst into a delirium of delight’ (19 April). 12

The report goes that Pavlova herself said,

To realise what the dance means for mankind, to realise the poignancy and the many-sidedness of its appeal, we must survey the whole sweep of human life, both at its highest and deepest moments. 13

Of that same debut performance, the Sydney Morning Herald of 19 April reported

The genius of Anna Pavlova captivated a great audience… Pavlova regards her achievements as part of a harmonious scheme, in which music and scenery are allied with the dance… Not only her feet, but her hands, share in the poetry of her movement… all is form and rhythm… made vividly eloquent in expression. Above all else is her magnetic personality. It is this quality which explains the pre-eminence of Pavlova. It inspires all that she does. 14

Pavlova was swiftly sowing her seeds: another article in the Sydney Morning Herald of 19 April reported that a lecture on The Ballet was given at Farmers department store by Mr William Asprey for the Musical Association, wherein he described Pavlova as “the great living exponent of the terpsichorean art”. 15 Even the Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate published a series of photographs of the ballerina.

On 22 April the Daily Telegraph published an interview with the caricaturist, Maisie Sommerhoff, who said,

I should think to dance with Pavlova is to bask in reflected glory, and the inspiration derived from such an experience is anything but negligible. An artist would be stone not to be transformed from such a contact.

She continued by saying that Pavlova had stated,

I put what is in me into my dancing, and I want to make my audience feel the same way, so that they will understand… In Australia you are enthusiasts too: especially in Sydney. I notice that your people here are quick at grasping the artistic side… My art means breath, life, and charm to me, and I try very hard to make my audience understand me… [your country is] very young yet, and art must have tradition… In the older countries, these traditions have helped to build the finest of art. I think this should inspire a younger country to high ideals. You do not have your own opera, no? What a pity, because I think there must be many beautiful voices in this country, where everyone is so happy. 16

Pavlova continued to captivate her audiences. On 1 May another large audience, which included the Governor-General Lord Stonehaven and his wife Lady Stonehaven,

was captivated by the ethereal grace of Madame Anna Pavlova… the Beethoven Rondino… was the very perfection of poetic grace and beauty.[[Pavlova. “Snowflakes” Ballet. The Beethoven Rondino’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 May 1926, 5.]

“Brain and senses alike respond to the artistry that is Pavlova’s”, reported the Daily Telegraph of 10 May. After seeing the new program in which Autumn Leaves had been presented,

one left the theatre confused with the cleverness of her feet, the power of expression in her hands, and the knowledge that her dancing is mental, not physical … Pavlova had the audience entranced, and there were many recalls. 17

Autumn Leaves was her own choreographic essay, as well as her own personal favourite. Set to music by Chopin, it was rarely out of her repertoire. The effect of Pavlova’s Autumn Leaves lingered.

Tawny-hued chrysanthemums and autumn leaves decorated the tea-table when Mrs. T.S. Saywell and Mrs. B.W. Saywell entertained at a farewell party in honor of Mrs. F.H. Saywell prior to her departure abroad. 18

The Sydney Morning Herald of 15 May published in an article by A.J.M:

it seems nothing could be more beautiful… till Anna Pavlova herself enters, and then is seen the supreme beauty of the full opened rose, performed, with personality. Subtly smiling, armed with every witchery, melting from one lovely mood and posture to andother [sic] as lovely… she enables people to forget for an hour the sadness of life … And not only to forget for an hour may be. I have a fancy that many of the audience, and not only the younger ones, may, consciously or not, move a little more gracefully, walk more buoyantly, and perhaps, appreciate and honour the wonder of their own bodies a little more fully because they have for a space watched “Great Anna” and her company of dancers. 19

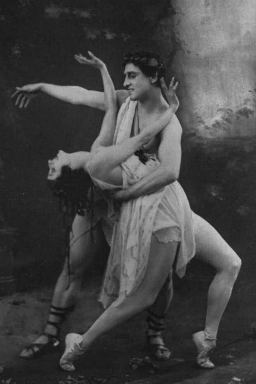

On 8 May in the same program as Autumn Leaves, Pavlova also danced Bacchanale with Novikoff. Algeranoff recalls, however, that it received no hand clap, and clearly could not have appealed to the opening night audience. The Daily Telegraph on 10 May reported that “It [Bacchanale] was a dance of desire, powerfully interpreted”, 20 and the Sydney Morning Herald on 10 May reported “[it] was simply a frenzied series of evolutions by the star and her dancing partner—amazing in their velocity, but at the same time too realistic.”

Pavlova and Novikoff striking a pose for the camera in Bacchanale, which displeased the audience and was considered by a Sydney critic to be ‘too realistic’. Courtesy: Barr Smith Library, the University of Adelaide.

Pavlova and Novikoff striking a pose for the camera in Bacchanale, which displeased the audience and was considered by a Sydney critic to be ‘too realistic’. Courtesy: Barr Smith Library, the University of Adelaide.Pavlova’s final week in Sydney saw the spectacular two-act ballet Don Quixote performed. This was the condensed version arranged by Laurent Novikoff, based on Alexander Gorsky’s 1902 version, and performed to music by Minkus. The first Australian performance had been given in Melbourne on 5 April.

The Daily Telegraph of 17 May reported,

Pavlova… was vivacious and intriguing, and she danced gloriously… The occasional posturings were artistic beyond the imagination, while her inspiration seemed to disclose itself in the work of her associates. The ballet is best described in one word—superb…To say that Pavlova was the perfection of her art… is to repeat the obvious… [she] was ‘better than the best’. 21

It was said that Sydney’s enthusiasm possibly even surpassed that of Melbourne’s. Pavlova had not only captivated her audiences, but also those who were not able to see her dance. On 7 May the Daily Telegraph published a letter to the editor dated 6 May from E. Llewellin:

Sir – How many Australians, at the close of the Pavlova season, will be able to say, “I saw Pavlova”? The answer to this question is “about 100,000.” Practically six millions of Australians would like to see Pavlova, but nearly six millions will not see her. I think some arrangement could be come to, whereby Australia, as a whole, might be permitted to view a Pavlova performance, per picture show. 22

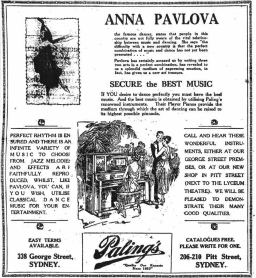

The magnitude of the public’s enthusiasm further had the consequence that Pavlova’s name and portrait were used to advertise all sorts of products including shoes, hosiery, hire-cars, confectionery and beauty products. The music retailer Paling’s was one of many companies who used her name and portrait for promotional advertisements. However, Pavlova “shared the traditional Russian suspicion of western commercialism, disliking the fact that she and her art had to be advertised and the way in which her name was sometimes used to promote various beauty products”. 23

While in Sydney, Pavlova attended a number of social functions, and although not fond of attending such engagements, she appreciated it was necessary for her to do so.

On 19 April, for instance, she attended and declared open the artist Blamire Young’s exhibition at the Macquarie Galleries. The crowd were disappointed because she gave no speech, only a “thank you” to the sculptor Sir Bertram Mackennal for his good words. Those attending a luncheon arranged by the NSW Institute of Journalists at the Smokeroom of Farmer’s Restaurant at 12.45pm on 20 April were a little luckier.

Replying to a toast to her health, she said,

You make everyone happy who comes here. I regret that I did not come here before, but I hope to come again. If you would like to do something in your country for my art, my Russian art, then I shall be glad to help you. I wish you happiness and prosperity. Your duty is to help your country to get these things.

The Institute’s president, C. Brunsdon Fletcher, who was the chairman, said,

Pavlova should be a lesson to our young folk. What Madame had acquired had resulted from endless labour. She had to begin early and remain late in her work, which had practically never ceased… she had been able to express herself through her art… was the perfection of art… There had been nothing like it. 24

Pavlova attended another luncheon on 27 April arranged for her by H.D. McIntosh M.L.C. at the Wentworth, which included many distinguished guests.

The Feminist Club at 77 King Street also entertained Pavlova, but this time she was given an interesting musical program on 14 May. Afternoon tea was provided by voluntary workers of the Golden Shower tea rooms. Three days later she was off to lunch with the Governor-General and a photograph of her at Government House was published on 18 May in the Daily Telegraph.

The final performance of the Sydney season was on 20 May. “Thank you very much. Au revoir.” 25 was Pavlova’s farewell ‘speech’, given, contrary to custom, at the close of the first act. The audience that night included the State Governor and Lady de Chair, as well as the president of the Russian Society of New South Wales (and a notable women’s hairdresser) John Datsis, who presented Pavlova with an address of appreciation and a bouquet.

The conclusion of the Sydney season saw the company depart by boat for a short tour in New Zealand. On her journey Pavlova had collected many birds which she transported in small cages, making larger cages for them when she stayed in a place for a while. The birds were left in Sydney while she was in New Zealand.From New Zealand the company sailed back to Sydney, and on the same night that they arrived they caught the train to Brisbane.

Because of a change in gauge size they had to change trains in Toowoomba and then a second time owing to a train derailment. They did not reach Brisbane until the second morning, very fatigued. They were happier with the warmer Queensland weather after the cold of New Zealand, however, and even went swimming during the weekend.

Pavlova appears in an advertisement for the Sydney music store Palings. Courtesy: Nina Melita

Pavlova appears in an advertisement for the Sydney music store Palings. Courtesy: Nina MelitaDuring the Brisbane season, which ran from 12 to 20 July at His Majesty’s Theatre, the artist Enid Dickson, in whose work Pavlova took an interest, did some sketches of the dancers. She was given permission to go backstage and sketch Pavlova on the stage from the wings. After three nights all she had managed to draw were her nose and eyes; she never managed a detailed portrait as she couldn’t take her eyes off Pavlova’s dancing. 26 The dancers’ return trip from Brisbane to Sydney took 28 hours, as the new rail line had not been completed.

After attending a function at the Adyar Hall on 22 July, Pavlova gave an afternoon charity performance at Her Majesty’s Theatre and the faithful Daily Telegraph reported next day that over £1,200 had been received, the expenses being minimal. The performance was to a capacity crowd, with many content to stand, and music incidental to the performance was broadcast by 2FC. During the recalls, amounting to about 15, and while again being showered with paper streamers, Pavlova was presented with a ‘flower-decked boomerang’ by a little girl who said to her, “And I hope it brings you back!” 27 Pavlova’s “Tribute to Australians” was published in the rival Sydney Morning Herald on 23 July.

After the matinee performance of 22nd in Sydney, the company continued that same evening to Melbourne for another charity performance to be given the next afternoon at Her Majesty’s Theatre. They changed trains as usual at Albury at 6am and on arrival in Melbourne immediately went to the theatre for the matinee, leaving their luggage at the station. As the scenery and costumes did not arrive in time the matinee was slightly delayed.

The audience, however, ultimately witnessed the unforgettable Autumn Leaves for the first time. After the performance, the great Russian bass, Chaliapine, who had just arrived in Australia on a tour for the Williamson organisation, paid Pavlova a visit with his daughter. All the proceeds of these two charity performances were donated to Pavlova’s Home for Refugee Russian Children at St Cloud in Paris and the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Sydney.

Pavlova made a point of giving such charity performances and worked endlessly for orphans. Pavlova’s Appeal for a mothercraft centre, ‘Karitane’, on behalf of the Australian Mothercraft Society, 28 was published in the Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate on 18 May and the Daily Telegraph on 11 May.

After the Melbourne matinee, the company continued their journey that evening on a special train to Adelaide. Gratefully, they were able to have some rest as the rail gauges were the same on this part of the trip and they did not have to change trains.

The farewell season in Adelaide was from 24 July to 14 August. It has been estimated that some 18 ballets and 55 divertissements had been presented during the Australian tour. On its conclusion, a number of dancers bid their farewells and left the company. J.C. Williamson made an offer to two dancers, Thurza Rogers and Robert Lascelles, to star in a musical, Tell Me More. Another dancer, Alexis Dolinoff, went back to Sydney and opened a ballet school where he taught the Cecchetti syllabus for two years.

Exhausted, the rest of the company boarded the ship Narkunda in Adelaide, disembarking only in Fremantle for an evening meal in Perth before re-boarding that night for the five-week journey home.