In this article, tracing the life of a distinguished dance artist, I hope readers will learn something of how the very Western art of ballet developed in the unique and sometimes difficult cultural, political and historic milieu in Japan after World War II.

My research for this article involved recent communications with Frederic Franklin and Jacques D’Amboise, as well as interviews with Tomotake Nakamura and his family, who shared Nakamura’s correspondence with American dancers and provided some of the photos in this article.

Tomotake Nakamura was born in 1931, the third son of a family who had founded a school near the Hongo campus of Tokyo University teaching kendo, the traditional art of Japanese fencing with bamboo swords first cultivated by 12th century samurai warriors.

In 1945, as fighting in the Pacific reached its destructive conclusion, nine year old Tomotake experienced the devastating air raids that incinerated metropolitan Tokyo, including his own family house. Fortunately, all of his family survived the inferno, and the war was soon over. After the end of the war came the occupation of Japan by the Allied Powers, which banned kendo along with other martial arts, and even calligraphy, as part of an American program intended to demilitarize and democratize Japan.

As a result, Tomotake’s father lost his livelihood. According to Tomotake’s oldest brother, who pursued kendo after the ban was finally lifted a decade later, the

real kendo was over when the war was over. Physical skill like kendo cannot be passed on if it is forbidden to practice for such a long time.

Tomotake grew up under the influence of his artistic elder brothers who, instead of kendo, studied fine art, music and literature. The brothers would often get together with their comrades and discuss their hopes for and ideals of peace and freedom, unconstrained by bans on Western activities, such as sports (e.g., baseball), social dance at dance halls and music (e.g., jazz) during the war and the reverse limitations on Japanese traditional activities by the Allied Powers in the war’s aftermath.

In 1948, three years after the end of the war, 17-year-old Tomotake was playing (American style) football in the park attached to the Imperial Palace, the official residence of the Emperor. He would have been mindful that not long before playing the sport of Japan’s official enemy would have been forbidden, even unthinkable, here at the central symbol of Japanese tradition.

After the football game, someone told Tomotake about a ballet class. Having been searching for an artistic outlet, Tomotake went to see the class taught by Yusaku Azuma, and for the next two years took lessons with him. Eager to improve his technique, Tomotake asked Mr Azuma if he could use the dance studio for practice outside class time.

The response was negative so Tomotake stopped going to Mr Azuma’s class. Instead, perhaps with memories of the kendo school, he went to the campus of Tokyo University and practiced jumping in the woods or on the intramural field. In these environments, so different from the dance studio, he felt challenged to jump higher.

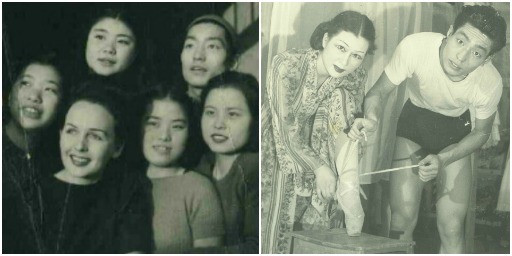

(L) Jane Burlow (second from left) and Tomotake Nakamura (second from right). (R) Yumiko Onishi and Tomotake Nakamura. Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, photographers unknown.

(L) Jane Burlow (second from left) and Tomotake Nakamura (second from right). (R) Yumiko Onishi and Tomotake Nakamura. Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, photographers unknown.In 1950, Tomotake started taking dance lessons from Jane Burlow, the wife of an American G.I., who had studied ballet with Bronislava Nijinska in Los Angeles, California, and danced in Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo before coming to Japan (Kubo, 2012).

Burlow was surprised to see many bad habits in Tomotake’s technique, the result of the fact that his first teacher, Mr Azuma, had learned ballet mainly from books. This deficiency was exacerbated by Tomotake’s unsupervised practicing, with no teacher to provide feedback. Burlow quietly mentioned to Yumiko Onishi, a young woman who had been taking her class for some time (and the future wife of Tomotake), that his aspirations towards ballet were hopeless.

Within a couple of years, Tomotake proved that prediction was mistaken. He absorbed Burlow’s styles—not only ballet techniques, but also jazz dance—and became her protégé.

An opportunity arose for Tomotake, Yumiko, and other students of Burlow’s to perform for a group of G.I. wives at the Tokyo Takarazuka (Toho) Theatre, temporarily renamed the Ernie Pyle Theater by the occupying G.I.s, wherein Japanese people were not allowed to enter as audience at the time. Tomotake danced boogie-woogie in a piece entitled Cocktail Party.

Impressed by his talent, a G.I. wives’ group wanted to sponsor Tomotake to study dance in the USA for a substantial period of time. However, in occupied Japan, he could only obtain a visa for three months, forcing the public-spirited wives to give up the idea. In the meantime, Tomotake and Yumiko took advantage of every chance to watch, learn from, and sometimes perform with ballet companies visiting from overseas.

In 1952 a French ballet company led by Serge Lifar performed Suite en Blanc and other pieces at Hibiya Public Hall in Tokyo. Tomotake, Yumiko and other Japanese dancers sneaked into the theater before it opened, hid themselves in the bathrooms until the performance started and, by that strategy, watched every performance of the company’s season.

Then in 1953, Tomotake and Yumiko encountered the legendary dancers, Frederic Franklin, Alexandra Danilova and Mia Slavenska, almost accidentally. After Tomotake had gained experience as a dancer and choreographer, he would often work for NHK, the nationwide Japanese broadcasting service.

One day, after he had finished dancing for a TV program, Tomotake left the NHK TV studio and set out walking with Yumiko, now his wife, to the Yurakucho neighborhood of Tokyo. Passing by the Imperial Hotel, Tomotake recognized the three famous dancers, whom he had heard through dance gossip that they were in Tokyo, just walking out of the hotel. Tomotake rushed forward, introducing himself as a dancer eager to dance with them. Franklin calmed down the nervous and enthusiastic young man by politely explaining that an audition would be held on the next day.

Alexandra Danilova and Tomotake Nakamura (above in black suit). Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, Photographer unknown.

Alexandra Danilova and Tomotake Nakamura (above in black suit). Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, Photographer unknown.Surprised and delighted to be chosen from among other, more established Japanese ballet dancers, Tomotake was selected to perform in A Streetcar Named Desire and The Nutcracker Suite. He believed he succeeded in getting a relatively significant part because he could dance both ballet and jazz, unlike the other dancers who came to audition.

His partner was Mia Slavenska. During rehearsals, Tomotake learned from Franklin how to support female partners with no hands but with the legs alone, and to lift female dancers with only one arm (Bronfeld, 1954).

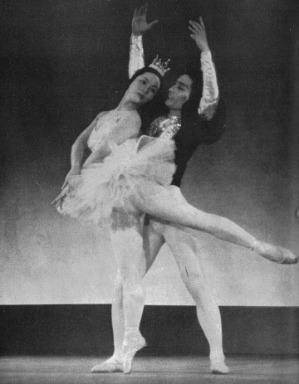

Mia Slavenska partnered by Tomotake. Photo Source: Dance Magazine September 1954

Mia Slavenska partnered by Tomotake. Photo Source: Dance Magazine September 1954As an adjunct member of the Slavenska-Franklin Company, Tomotake toured to Nagoya and Osaka. When the Franklin Ballet left Japan, Franklin told Tomotake that the company was scheduled for a tour entertaining the Allied troops around Korea. Franklin suggested that, when the company returned to the US after the planned Korean tour, he would find a way to get Tomotake to America.

However, the Korean tour was cancelled due to the worsening political situation in that country. Soon after, the Franklin company dispersed and Tomotake missed his second and last chance to visit America as a dancer.

Tomotake Nakamura partnering Mia Slavenska in A Streetcar Named Desire. Photographer: Mihori

Tomotake Nakamura partnering Mia Slavenska in A Streetcar Named Desire. Photographer: MihoriRemaining in Japan, Tomotake matured as a dancer and also established himself as a choreographer, TV producer and dance instructor. While dancing in the Matsuyama Ballet Company in Tokyo in 1954, Tomotake choreographed Peter and Wolf to the music of Sergei Prokofiev for the company (Japan European Dance History Research Association, 2003).

In the same year, Colette Marchand and Milorad Miskovitch formed the Marchand Miskovitch Ballet in France and toured Japan. Tomotake auditioned for the company, passed the audition, and danced The Miraculous Mandarin to music composed by Béla Bartók with Colette Marchand.

Before this incredible opportunity, Tomotake had seen the actress in the 1952 British film, Moulin Rouge, which won her an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. But this time, it was he who was dancing with and physically supporting the film star on the stage.

In 1958, the New York City Ballet (NYCB) toured Japan with Maria Tallchief, Patricia Wilde, André Eglevsky, Allegra Kent, Arthur Mitchell, Melissa Hayden, and Jacques d’Amboise. 1 Tomotake was no longer actively performing on stage, but choreographing for television productions and teaching dance classes.

Despite this, he still had a chance to perform with the company in a minor role in The Nutcracker. He also had opportunities to take ballet lessons with André Eglevsky, and study jazz dance with Arthur Mitchell. Yumiko served as a dresser for Maria Tallchief.

Tomotake and Yumiko travelled to Nagoya and Osaka with NYCB, which involved changing steam locomotives one after another along the Pacific Ocean coast line. When the train stopped at stations, Tomotake and D’Amboise used the opportunity to leap and dance on the platform. D’Amboise recalls:

it was a common habit of mine with other dancers to compete in dance. 'How many turns can you do to the right?... Let’s do double tours. …'Let’s see how many we can do before one of us falls over'.

Tomotake had heard of D’Amboise’s experiences performing in the film Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and in and around these impromptu competitions, discovered how the American star had learned to jump onto logs for one of the famous scenes of the movie choreographed by Michael Kidd.

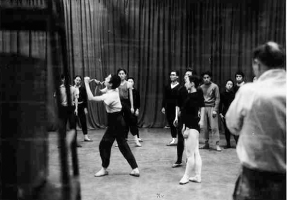

Tomotake Nakamura choreographing Incredible Flutist for a NHK TV program. Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, Photographer unknown.

Tomotake Nakamura choreographing Incredible Flutist for a NHK TV program. Source: Yumiko Onishi's collection, Photographer unknown.After the Slavenska-Franklin Company left Japan in 1953, both Tomotake and Yumiko kept in correspondence with one of the company members, Lee Becker. In 1983 Becker (now Lee Theodor) came to Tokyo leading the American Dance Machine (ADM), a company aiming to preserve American musical dance, which performed at the Koma Theatre.

She took the members of her company to Tomotake’s and so the strands of interaction between dancers from the States and Japan continued. During the last two decades, the theatre arts have declined in popularity in Japan, alongside the specialised theatre venue which was becoming dilapidated. In May 2008, sadly, this particular theatre was closed down.

In the 1980s, Tomotake stopped choreographing and producing for the genre of children’s TV programs that he had pioneered in Japan since 1960s. Instead, he focused on teaching, establishing his own ballet studio, the 'Tomotake Nakamura Ballet Research Institute' on the top floor of the theatre arts complex in Shinjuku, Tokyo.

In the mid 80s, I was preparing myself to study dance therapy in USA, taking dance classes with Nina Werness at the American Dance Machine Tokyo which had established a continuing base in the Roppongi neighborhood. Recognizing my unique learning needs, she thought I would benefit from studying with Mr Nakamura. Werness described Mr. Nakamura to me as "the best kept secret human treasure of a dance artist in Japan". I thus entered Mr. Nakamura’s studio and experienced for myself how he taught dance technique and expression.

Into his fifties and sixties, Mr. Nakamura was still a brilliant turner and jumper; performing several revolutions of pirouettes from a single preparation and wonderfully demonstrating how to achieve the elusive effect of lightness that dancers call ballon. The intention of his spectacular demonstrations was to show his students how to achieve these specific skills. For example, he would borrow a toe shoe from a female dancer, put in on, and display how the added degree of pivotal freedom allowed him to spin faster and achieve more revolutions.

One of the many dancers who took class with him at his studio was Koichi Kubo who currently dances in the Colorado Ballet. In a 1998 Dance Magazine cover story interview, Kubo described his two years of study with Nakamura:

It was so hard, it was the hardest time in my life, but I was proud that I didn't try to run away from his class. He was a very tough guy. He didn't let me give up; the key was, don't ever give up. (Gastineau and Schatz, 1998, p. 66)

As a fellow student in Tomotake’s class at the time, I remember Kubo’s extraordinary turning skill and also how much he liked to demonstrate this virtuosity at every opportunity. This cockiness was harshly scolded by Mr Nakamura. "Dekirukoto bakkari yatterunja naiyo!" (Don't waste your precious time with me for something you can already do! You have lots of other things that need to be improved!)

As demanding and as skilful a teacher as he was, Mr. Nakamura’s focus centred, unwaveringly, on the goal of developing his students' full potential. Mr. Nakamura would often sit on his favorite director’s chair next to the piano, intensely observing his students. Immersed in this mission to enhance the students’ talent, his facial expressions and words were often unforgiving. Indeed, he had an intimidating reputation of being one of the most demanding teachers in Japan.

By contrast, Mr. Nakamura could evoke extreme happiness when he demonstrated ballet or jazz combinations for us, his body transformed by the lightness and ease of movement and his visage expressing profound joy. When he realized that dancers were too caught up with technical details, he would jump up from the director’s chair, and show us that it was actually possible to dance with full expression, even when executing highly complicated technique or combinations.

Outside classes, the Nakamura family—Tomotake, Yumiko and their daughter, Kumiko—entertained us all, from young children to middle-age dance teachers, by throwing parties at the studio with a spread of delicious homemade food. Unlike his formal self as a teacher, Mr. Nakamura was smiling, friendly, and talkative at the parties.

Responding to questions, he retold the stories of his fascinating encounters with international dancers soon after the war. The themes of our discussions ranged over dance history, criticism, and philosophy—not to mention the hopes and ideals of contemporary dancers. Indeed, the studio was a research institute of dance theory and practice.

Together, Nakamura, Yumiko and Kumiko continued teaching new generations of dancers at the studio into the 21st century, until Nakamura’s physical condition deteriorated after 2005. Nakamura passed away on 4 May 2008 from a stroke, survived by his daughter, Kumiko who studied in and supported the dance studio until the end.

References

- Bronfeld, S. 1954. Ballet in Japan. Dance Magazine, 28, 38 – 54.

- Gastineau, J. & Schatz, H. 1998. Standing tall. Dance Magazine, 72, 64 – 69.

- Kubo, M. 2012. Jane Burlow. Accessed on 22 November 2012. [Japanese]

- Japan European Dance History Research Association [Nihon Youbushi Kenkyu Kai]. 2003. Japan European Dance Historical Calendar 1900 – 1959 [Nihon Youbushi Nenpyo 1900 – 1959]. Tokyo: Japan Society for Promotion of Art and Culture [Nihon Gejyutsu Bunnka Shinkoukai]. Accessed on 22 November 2012. [Japanese]

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Jonothan Logan for editorial and research assistance in New York.