But if you start laughing at anyone who’s ugly or deformed everyone will start laughing at you. You’ll have made an awful fool of yourself by implying that people are to blame for things they can’t help – for, although one’s thought very lazy if one doesn’t try to preserve one’s natural beauty, the Utopians strongly disapprove of make-up.

Thomas More, Utopia (1516)

Thomas More’s quotation testifies to a long-established debate concerning attitudes to physical otherness or divergence from bodily norms. In his Utopia, it would appear that corporeal differences are not only accepted but celebrated as part of the essence of humankind—not to be covered over. In the late 20th century, stage dance emerged as a key avenue to celebrate human diversity by encompassing a range of people with different abilities and disabilities.

Integrated dance involves a mixture of people with and without disability, thus symbolically representing the wider population and society more accurately than its counterparts in mainstream dance. Choreography can serve as a vehicle for societal change, seeking to disrupt preconceived public perceptions of disability and de-stigmatise disabled people. 1 It thus parallels in many regards the disability social movement, which integrates individuals with disabilities with the non-disabled, in pursuit of a more inclusive society.

This paper investigates integrated dance centring on New Zealand. It thus fills a significant gap in existing literature, as the scholars who have addressed integrated dance have tended to focus on US- and UK-based companies (e.g., Albright 1997; Benjamin 2002), largely ignoring developments further afield. Integrated dance is still in a development phase throughout the globe, and our local investigation may promote reflections and provide opportunities to develop visions and directions elsewhere in the world.

The intent of this paper is twofold: First, to examine theoretical perspectives on dance and disability which provide useful frameworks within which to analyse specific choreographies. This is broached by a discussion of the "ideal dancing body" and strategies for how the disabled body may reiterate or disrupt such constructions.

Acknowledging that the perception of disability on stage is contingent on the audience’s own preconceived notions of disability as well as the performance itself, we shall also discuss various viewing strategies for integrated dance. Secondly, we offer concrete analyses of two choreographies—This Word Love (1999) and Picnic (2002) by Touch Compass—New Zealand’s first integrated company (Powles 2007)—as an illustration of the ways in which disability and the dancing body on stage are constructed through choreographic imagery and iconography.

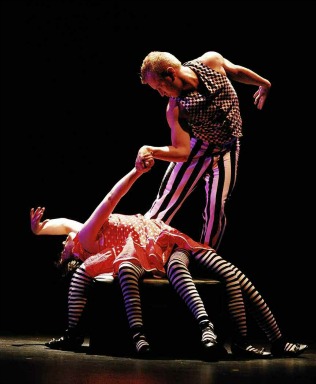

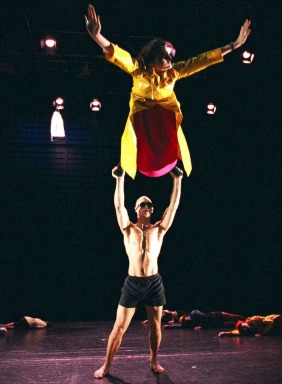

Renee Ryan and Connor Kerr in Homeland, Jolt Annual Show, 2011. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.

Renee Ryan and Connor Kerr in Homeland, Jolt Annual Show, 2011. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.Dance and disability

In New Zealand, two major integrated dance companies work with disabled dancers: Touch Compass Dance Trust, founded in 1997, and Jolt Dance Company, set up in 2001. These integrated dance companies were influenced by developments beyond the Australasian region, in particular in the USA and Europe.

In the 1960s and 1970s many postmodernist US-American dance artists included improvisation and physical theatre within their movement styles and thus began to challenge traditional notions of dance performance. Yvonne Rainer, for instance, aimed to produce work which was deliberately non virtuosic, make-believe, stylised, or glamorous, as proclaimed in her famous ‘NO’ manifesto from 1965. Her contemporary Trisha Brown took dance performance away from the proscenium stage into previously ‘unused’ spaces, for instance by creating suspension works on the outside walls of inner city buildings.

Although these performances did not feature disabled dance(rs) per se, they are indicative of developments in dance which, as scholars have rightly argued, paved the way for the birth of integrated dance (Benjamin 2002). 2 According to Ann Albright, the use of contact improvisation in the 1980s chiefly influenced the establishment of integrated dance as it led to an increased interest in the exploration of physical exchange between people with different kinds of bodies (Albright 1997). Many integrated companies were formed across America in the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as AXIS in Oakland, California, and Light Motion in Seattle, Washington. At the same time in the UK, community-based integrated companies were beginning to grow in numbers. Touchdown Dance, a company for partially sighted, blind and sighted dancers, was co-founded in 1986 by Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton who is also known as the father of contact improvisation (Benjamin 2002). In 1991, CandoCo was founded and became the first professional British integrated dance company to tour nationally and internationally (Benjamin 2002).

Aleasha Seaward and Melissa Fox in Untitled. First performed in 2010 from ‘Still’, Christchurch Art Gallery 2010. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.

Aleasha Seaward and Melissa Fox in Untitled. First performed in 2010 from ‘Still’, Christchurch Art Gallery 2010. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.These progressive changes within the Western dance world developed in parallel to the disability movement in Western societies, which helped prepare audiences for public performances by disabled dancers. During the 1980s many minority groups worldwide, including people with disabilities, began to voice their right to have control over their own lives and make decisions that directly affected them (Tennant 1996).

The disability social movement rejected earlier perceptions of disability—which were retrospectively encapsulated into the medical model—in favour of what is termed the social model of disability (Oliver 1990). The medical model had viewed disability in terms of some kind of deviation or deficiency from what was considered the range of "normal human function".

People with disabilities were thus regarded as inferior to the non-disabled (Sullivan 1997). The social model, on the other hand, incorporates a broad cultural understanding of disability experiences, such as stigma, representation of disability in the arts and the media, and the history of institutionalization. Disability refers to an identity, as many people view their disability as an important part of who they are (for example the Deaf community); it is a cultural and societal phenomenon somewhat akin to race, gender or sexuality (Tennant 1996).

Reconciliation between the two models has been sought by developing a comprehensive model and a new independent model. As an example of the former, the World Health Organisation overarches the two older models by distinguishing between impairment and disability. Impairment is defined as a loss or abnormality of physical bodily structure or function, whereas disability was first defined in terms of limitation or functional loss derived from impairment in 1980, and then more recently as activity limitation in 2000 (World Health Organisation 2000).

Such definitions of disability are not at all applicable to integrated dance in which dancers with disabilities are not represented as limited or dysfunctional as dancers. Minae Inahara (2009), by contrast, transcends the debate between the medical and social models, by claiming that all bodies are, in effect, able:

all people are represented by only one body, the able body, and … physical disability cannot be defined except as the supposed opposite of the mythical able-bodied. (Inahara 2009, 52, our italics)

This perspective is perhaps the most useful to guide our investigation into the emergence and development of integrated dance in New Zealand.

Both the disability arts movement and social movement seek to de-stigmatise disability, on the one hand through a change in public perceptions by challenging non-disabled people to (re)evaluate their own preconceived notions and attitudes towards it, and on the other by enhancing self-determination and pride in disability identity (Morrison 1993).

New Zealand television programs on disability, such as the documentary series Inside Out (1998 – 2004) and festivals such as Giant Leap (2005), New Zealand’s first international disability arts festival, give visibility to both professional and community artists, including those working in dance, who inform the wider public about disability-related issues and can become role models for disabled viewers.

Embracing broader aesthetics

Dancers with disabilities not only struggle against societal prejudice, but also against the strictly confined body image in much Western theatre dance. The ideal form in 17th-century ballet incorporated, for both sexes, the ability to maintain elegance and decorum through uprightness, ease and effortless control in order to conceal physical exertion (Au 1988; Foster 1986). Although theatre dance throughout the 20th century challenged the strict impositions of classical ballet aesthetics, comparable notions of artistry are common in many non-balletic companies.

As Owen Smith argues, even contemporary dance often promotes an exclusive, homogeneous type of body (Smith 2005). While the professional dance world is clearly not unified in terms of body image, since each genre or style trains dancers to produce and foster a particular aesthetic which is often unique to that style (Kuppers 2000), virtually none of them, including contemporary dance, have consciously included the disabled dancer.

Hence, the appearance of such dancers within mainstream stage dance has been an important stepping stone towards challenging its elitist genesis.

Yet, integrated choreography itself also needs to create new and inclusive aesthetics if it is to promote positive images of the disabled body. If choreographers fail in this task, the movements of the disabled dancer may simply recreate and reinforce nondisabled aesthetic ideologies.

Ann Albright, a writer on feminism and dance, illustrates how this may be achieved within choreography and movement forms employed by various integrated dance companies. She draws on Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories to posit that disabled dancers can force viewers to "confront the cultural opposite of the classical body—the grotesque" (Albright 1998). The grotesque body image has the power to destabilise the status quo.

According to Bakhtin (1968), it is continually changing and never complete, in contrast with the classic body image which is entire, smooth and self-contained:

that which protrudes, bulges, sprouts or branches off is eliminated, hidden or moderated. All orifices are closed (Bakhtin 1968).

Most Western theatre dance, particularly ballet, promotes the classic image. Dancing bodies are expected to be homogeneous, exhibiting physical control and technical virtuosity; dancers must perform with closed mouths, showing a physicality that is clean, smooth, totally separate and distinct from the outside world.

A disabled dancer might physically differ from the norm of the ‘ideal’ dancing body and therefore challenge conventional restrictions as to who can dance. However, as noted above, the actual choreography too is instrumental in destabilising these classic aesthetics, for otherwise the disabled dancer may simply recreate the ‘ideal’ bodily image within his or her work, for instance by endorsing classical lines, arm postures and technical skills while deemphasising any divergence from non-disabled norms.

Recognising this danger, the New Zealand choreographer and academic Suzanne Cowan has made use of the exaggerated nature of the grotesque to maximise difference rather than trying to minimise it. Cowan has what she refers to as two "floppy legs" (she is a wheelchair user), so in her performance Grotteschi (2008), she added four more such legs to her costume to become Ava the Amazing Spider Woman (Cowan 2009).

One strategy used by disabled performers to challenge the often unspoken question "what happened to you" behind the curious gaze of the public is one of hyperbole (Sandahl 2005). Cowan chooses not to deny but instead reclaims her stigma, resignifying it through a rather humorous portrayal of Ava who seduces her acrobatic duet partner before devouring him. With six floppy legs, Ava appears a strong and confident character capable of capturing the most difficult prey.

Suzanne Cowan and Adrian Smith in Grotteschi. First performed in 2008. Photo: Kathrin Simon. Courtesy: Touch Compass.

Suzanne Cowan and Adrian Smith in Grotteschi. First performed in 2008. Photo: Kathrin Simon. Courtesy: Touch Compass.The exacerbation of difference appears possible because, as Cowan states, audience reception of integrated dance has changed:

I think we have gotten over the shock value of, oh my god, it’s somebody with a disability dancing ... so then that enables people to actually see what’s happening, what kind of movement they’re really offering (Cowan 2009).

Cowan suggests that audiences now appreciate integrated companies for movement aesthetics that are different from the classical ideal because they are more used to seeing diverse bodies on stage. However, it is necessary to sound a note of caution here as this might only be true for regular dance goers who have attended a wide range of performances.

Newcomers to integrated dance, who have only been exposed to dance forms with strictly selected body types or mainstream media representations of dance such as those in blockbuster dance movies, might still experience this initial shock. Possible discrimination against people with disabilities might in these cases still be wedded to normative audience expectations as to how dancers’ bodies should look.

Viewing strategies

While Cowan’s choreography seeks to destabilise conventional notions of disability and dance, the association of disability with the grotesque might be seen to have the opposite effect on some viewers, namely to reinforce the notion of an ‘ideal’ dancing body. It is important therefore to consider how a dance might be viewed.

Dance scholar, Whatley (2007) suggests there are different viewing strategies when watching disabled dancers. She argues that audience members are likely to bring certain preconceptions and expectations to the performance which will influence their viewing position. A particular frame of reference when watching a performance might determine what aspects of it are attended to and the kind of expectations an individual has about artistry and virtuosity.

Whatley points out that due to the dynamic relationship between the performer and viewer, a spectator’s viewing position may also shift as the performance progresses. A certain choreographic approach might promote a particular viewpoint, and factors such as proximity, setting and the viewers’ prior experiences play a major role in this process.

For instance, Whatley’s passive conservative strategy refers to those who judge integrated dance with an internalised expectation of a classical aesthetic. Choreographers themselves may promote or instantiate this by producing work which reflects a classical body image through the disabled dancers.

In a critique of CandoCo’s work I Hastened through My Death Scene to Catch Your Last Act (2000), the reviewer Tay (2000) not only openly compares the dancers to a classical aesthetic but appears to bring a classic perspective to his account of the performance. His judgements are made based on what does and does not look ‘pretty’, including an assumption that a true presentation of disability is one of "frustration, desire and longing."

The sight of paraplegics dragging themselves by their upper bodies, their lower extremities sliding flaccidly around the floor, was in itself another way of saying "reality is not pretty, deal with it." (Tay 2000)

Even when a choreographer challenges classical ideals, as Whatley points out, if viewers do not actively question their own perspectives then their judgement and interpretation may still adhere to such expectations (Whatley 2007). Tay’s review of CandoCo seems to illustrate this tendency.

The use of hyperbole and humour, as seen above, is a strategy used by some disabled performers such as Cowan to undermine conventional aesthetics and audience expectations.

However, this too can be problematic because audience members who adhere strongly to a classic aesthetic may indeed have this preference reinforced by performances that associate disability with the elements of the grotesque. This is not to say that performers should altogether avoid this strategy; it may assist audience members to release the stigma associated with dancers with disabilities, and instead appreciate a new aesthetic produced by them.

Here it is useful to draw on Whatley’s active witness viewing position. When viewing in this way, disability becomes "ordinary": it is seen as just another source of possibility within dance performance, albeit one which carries the potential for change (Whatley 2007).

Whatley, citing Kuppers (2003), points out that a performance can actively encourage this particular type of viewing experience. When a choreography explores the movement possibilities of each dancer rather than trying to fit or mould him or her into a classic aesthetic, viewers are more likely to view the performance from the active witness position. The review of a performance entitled A Wing/A Prayer (choreography: Mark Tomasic) by the US-American company Cleveland Dancing Wheels illustrates this: the reviewer Sucato (2006) describes the unique movements that are possible with a wheelchair, rather than looking for ways of transcending the disability:

The work pushed the wheelers in daring pops and rocking of their chairs along with precision turns and group formations … dancer Charlotte Heppner zipped about with ferocity and abandon … (Sucato 2006)

Viewed from this position, the dancers are seen as creating new ways of interpreting the body in performance that allows a shift in aesthetic and a less judgemental view of the body.

A critical analysis of Touch Compass

We now turn to consider in depth two works by Touch Compass Dance Trust, a non-profit organisation founded by Catherine Chappell based in Auckland, which has, according to Powles (2007), pioneered the way for integrated dance in New Zealand. The trust provides education, training and performance opportunities for dancers with and without disabilities. Their educational programs include community classes, professional development for dancers and teachers, and school workshops.

According to a statement on their website, Touch Compass’s mission is to produce professional, integrated dance performances and training for people of all ages and abilities; expand perceptions of ‘who’ is a dancer; and empower participants and inspire audiences through innovative, ground-breaking dance and theatre work, programs and events (Touch Compass Dance Trust 2009).

The company tours nationally and occasionally takes work to Australia, and several disabled Touch Compass dancers have gained employment with successful international integrated companies: Suzanne Cowan, for instance, has danced with the UK-based CandoCo, and Rodney Bell is now a member of the US-based AXIS Dance Company.

Matt Gibbons and Bronwyn Hayward in Lighthouse, 2002. Photo: Todd Antony. Courtesy: Touch Compass.

Matt Gibbons and Bronwyn Hayward in Lighthouse, 2002. Photo: Todd Antony. Courtesy: Touch Compass.Touch Compass employs a collaborative approach to the choreographic process, which means that dancers and choreographers work together to create their dance performances (Powles 2007). The disabled members occupy many roles within the company as dancers, choreographers and administrators, thus demonstrating partnership and power-sharing principles which are characteristic of the disability rights movement.

It is important to note that their work should not be misconceived as mere therapy for the company’s disabled members. In a television current affairs show 60 Minutes which was broadcast in 1998 on TV New Zealand, Chappell (1998) was questioned as to whether art or therapy was paramount. She replied that their work truly was art, adding that any therapeutic gain was just a by-product of the choreographic process and beneficial to all company members (see also Powles 2007).

This Word Love

1999

This ten-minute piece, choreographed by Carla Martell and premiered in 1999 at Maidment Studio Theatre in Auckland as part of Touch Compass’s RESIN8 3 season, explores expressions of love in human relationships (Touch Compass Dance Trust, 2008).

The set, lighting and space used throughout the entire work are minimalist. The set incorporates a black wall and floor, and the lighting creates four uneven rectangular spotlights which are used by the four dancers: two women and two men. One of each gender use wheelchairs, which they remain in for the entire dance. The other two dancers appear to be physically non-disabled.

The choreography incorporates several duets which explore love in various guises. There are five short sections in total, distinguishable by musical changes and pauses in movement. The first begins with a gestural phrase performed solo by the female disabled dancer; in the final section the same phrase is performed as a quartet.

The soft and flowing gestures suggest everyday activities and emotions; for instance, alternating the hands in up and down movements as if imitating a walking pattern. There is an emphasis on ‘love’ gestures within these sections, such as holding the arms in a cross shape against the chest and pulsing the palms of the hands (one on top of the other) on the chest.

The second section comprises variety of duets that appear to establish reciprocal relationships between the dancers. In the past, in particular before the 1970s, society promoted a culture of dependency of disabled people economically, politically and professionally: viewed as dependent minorities, many were institutionalized and exclusively reliant on service provision. This was also reflected in their representations in the media, arts and literature (Oliver 1990).

However, the duets in this section suggest mutual relationships between people with and without disabilities rather than the dependence of one on another. For instance, a wheelchair dancer pulls forward on the shoulders and arms of their non-disabled partner to initiate the collapse of the torso, and the non-disabled dancer then pulls back on the wheelchair dancer’s shoulder to initiate recovery to an upright position.

The first two duets separate the genders, before evolving into a duet for the two non-disabled dancers positioned between the wheelchair users. This in turn leads into further duets involving first the female non-disabled dancer and male wheelchair dancer, and then the other pair. While the music suggests romance and seduction with its light-hearted, jazz style complete with saxophone, the choreography does not entirely fit this theme, consisting as it does of a combination of duets based on pushing and pulling movements, release and recovery which conjure the emotional ups and downs associated with relationships of many different kinds.

By contrast, the third section involves a duet between the non-disabled dancers which the disabled dancers watch unfold from the sidelines. The disabled pair, who remain relatively still, frame a confined space for the non-disabled dancers to move in. The non-disabled dancers, in turn, often use the frames of the chairs to prop themselves up and balance on, therefore occasionally breaking out of the space set by the wheelchair dancers. The movement revolves around tension, resistance, pushing and embracing.

For instance, the male dancer with his hand on top of the female dancer’s head pushes her down. She resists as she gradually slides down the wall. The male dancer sits on the female dancer’s lap, but she looks away with a cheeky smile and pushes him off. The layered, progressive music invokes carnivalesque images of drunkenness and quirkiness; the tension and resistance in the movement along with impudent smiles depict a flirtatious and teasing encounter between a man and a woman.

There is thus a marked contradiction between the second and third sections of the dance. The second section involves reciprocal movement patterns between all participants, but the third draws a sharp distinction between the passive disabled performers on one hand, and the flirtatious non-disabled pair on the other. The former remain in the same lateral position, while the non-disabled dancers move around throughout the entire work, often quickly so as to create new duets. They easily pop up onto the wheelchair frames and balance off the ground; the wheelchair dancers thus providing a stable base for their acrobatic manoeuvres.

Jolt Youth—Sam Kahn, Rochelle Waters, and Jessica Stevens in Jolt Annual Show, 2012. Photo: Carolyn Jenson. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.

Jolt Youth—Sam Kahn, Rochelle Waters, and Jessica Stevens in Jolt Annual Show, 2012. Photo: Carolyn Jenson. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.This section admits of more than one interpretation. It is, with some goodwill, plausible to argue that it is a deliberate choreographic ruse whereby the ‘curious’ gaze to which many visibly disabled people are subjected is turned onto the non-disabled dancers. Here, it is the disabled performers who look upon the non-disabled ones, thus reversing the common tendency for the public to scrutinise disabled bodies (Kuppers, 2000; Sandahl & Auslander 2005).

The term "diagnostic gaze" has been used to describe this, and disabled performance artists use strategies such as hyperbole to expose these dynamics, as in Cowan’s work described above. However, if this was the choreography’s intention, then it does not quite manage to portray the role reversal successfully, as the dancers in wheelchairs appear more as bemused onlookers than as seeking to work out what is "wrong" with the dancing couple.

The more obvious reading of the scene suggests that once the choreography becomes more risqué, the dancers with disabilities are reduced to "framing" devices and outsiders witnessing an amusing and erotically-tinged encounter. The framing in This Word Love sets up a distinction whereby the disabled dancers appear relatively passive in comparison to the non-disabled. The framing of the entire work within a small area provides an intimate atmosphere well suited to an exploration of love.

When the wheelchairs create an even smaller space for the non-disabled performers’ duet, the space becomes almost suffocating, enhancing the intensity and the sexual tension of their encounter. While fortifying the drama between the non-disabled artists, however, this scene also gives the impression that one can move much more freely on legs than in a wheelchair. This evokes negative connotations of being "wheelchair bound" or "confined to a wheelchair", terms which are often used in the media instead of the more neutral "wheelchair user".

The use of the wheelchair dancers as inactive framing devices and props, contrasted with the energetic dynamism of the non-disabled couple, thus propagates a common (mis) conception of disability. In fact, research has demonstrated that wheelchair users often find that their chairs increase their mobility, speed and agility (Haller 2006; Kailes 1985).

Equally importantly, the disabled dancers’ lack of overtly displayed sexuality during the others’ flirtatious duet reinforces an image of disabled people as ‘asexual’: an issue which has been addressed in scholarly literature. Research has shown that non-disabled people often believe it is inappropriate for the disabled to engage in sexual activity and that disabled people should not produce children (Anderson & Kitchin 2000).

Reproduction thus seems to be traditionally viewed as a privilege of the "fittest" with an emphasis on their offspring’s survival, and not on the pleasurable aspect of sexual activity (Tepper 2000). People with disabilities are often portrayed as either uninterested in sex, unable to engage in it or—if they do—to feel any associated pleasure (Milligan 2001; Anderson 2000; Tepper, 2000; Longmore 1985). This idea, clearly an absurdity, usually relates to people with physical disabilities (Milligan 2001).

Its opposite extreme is the myth that people with psychiatric disabilities have an unrestrained libido; that they are unable to control their desires and feelings and are therefore unable to engage responsibly in sexual relationships (Milligan 2001). A famous example of this is the character of Bertha, Edward Rochester’s first wife, in Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre published in 1847. Bertha is not only portrayed as mentally ill, but as a violently sexual woman who cannot sublimate her wild desires. A femme fatale, she is depicted as the incarnation of evil and a legal impediment to Rochester’s ‘responsible’ marriage with Jane and thus to his happiness.

Our analysis of This Word Love has suggested that while it contains moments of mutual physical exchange between disabled and non-disabled dancers (particularly in its second section), the piece overall tends to reinforce the classical notion of the ideal dancing body. The disabled performers’ static, prop-like roles and minimal use of space in contrast with the lithe and active movement vocabulary of the dancers without disabilities seems to encourage a passive conservative viewing position, whereby the audience perceive the dance with the expectation of a classic aesthetic.

Given the topic—love, as indicated in the title—this work would have been a perfect opportunity to deconstruct the association between disability and asexuality by presenting unconventional images of sexuality in disabled people. Sadly, however, this opportunity was missed.

Julia McKerrow, Melissa Fox and Jane Mieka in Homeland, Jolt Annual Show, 2011. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.

Julia McKerrow, Melissa Fox and Jane Mieka in Homeland, Jolt Annual Show, 2011. Photo: Sean James. Courtesy: Jolt Dance Company.Picnic

2003

This piece is just six minutes in length, one of Touch Compass’s three short films from the Acquisitions 03 season (Powles 2007), directed by choreographer and videographer Alyx Duncan and produced by Catherine Chappell. It centres on a countryside picnic set in an old run-down, abandoned building.

The choreography appears to be improvisational: the dancers explore with movement low to the ground in a courtyard area before dancing on a wall and subsequently frolicking wildly in the open field. The film involves seven dancers with disabilities (two of whom are wheelchair users) and six without, as well as a three-legged dog.

The first shot is of a young girl who has no hands and is perched in a small wall aperture sleeping. When she awakes, she discovers adults around her having a picnic and attempts to gain their attention. The adults, dressed in beige and white colours, engage socially in small groups of two or three, talking, laughing, eating and drinking but shoo the girl away as she approaches them. The girl gives up, sits in the aperture and drifts off to sleep. After some time the adults too fall asleep. The girl wakes up again, follows the three-legged dog up some stairs and is surprised to find the same adults as before dressed in vibrant reds, inviting her to dance on a wall and subsequently on the grass.

As the credits roll, the adults can be seen leaving the picnic area waving goodbye to each other as they go their separate ways. Here the film colour changes to black and white; perhaps an ironic allusion to the silent era during which the industry used characters with disabilities to portray comic figures, beasts or objects of pity (Norden 1994).

The film plays with the formal property of ambiguity—a typical feature of art house cinema (Cf. Bordwell 2003)—as it is difficult for the viewer to distinguish between reality and fantasy or dream; several figures, notably the young girl, are shown sleeping and waking during the piece.

Are viewers witnessing the young girl’s or the adults’ dreams? Which part of the film is reality and which fantasy? The tension between the "real" and "imagined" is furthermore underscored by the loosening of causality, the eccentricity of many of the movements, and their execution in slow motion or time lapse, engendering an air of surrealism that allows for multiple readings.

In the beginning of the film, which is shot from the young girl’s perspective, the camera is positioned at low height in courtyard of the abandoned building and pans left and right. Apart from a very short female adult dancer and the wheelchair performers, the other dancers sit, lie and move about in a crouched position to remain within the camera’s view. Later in the film, after the girl has ascended the stairs, the camera remains lowly positioned but is held at an acute angle, compelling the viewer to look up at the dancers, which in turn empowers them.

The film thus progresses from images of confinement shot from a low-positioned camera and symbolised by square shapes, crouched movements and muted colours, to images captured in the high camera angle which portray the blue sky and ocean, larger movements and vibrant colours to evoke associations of freedom and power. Perhaps these contrasting scenes signify a shift from a restrictive world which marginalises minority groups, such as people with disabilities, to one which embraces diversity and empowers everyone regardless of their (dis)abilities.

This reading is underscored by the fact that in the first scene disability is concealed, whereas in the second scene it is in full view. In the former, the wheelchair of a female dancer with cerebral palsy is covered with a white cloth, resembling an armchair. In the latter, after the girl has climbed up the stairs, the dancer races across the grass with her chair no longer covered at all. Moreover, in the first scene it is hard to recognise that one of the adult dancers is very short as everyone moves low to the ground, while in the second part of the film the dancers’ different heights are much more visible. Hence, the film progresses from hiding visual signs of disability to offering much more overt and active images of disabled people.

The choreography thus explicitly goes against the grain of covering up visible signs of disability and otherness, signs that are tabooed within and outside the dance realm in a society which demands a controlled body: "control over ageing, bodily processes, weight, fertility, muscle tone, skin quality and movement" (King 1993). A New Zealand-based example of the pressure to cover over what might be perceived as a grotesque body in Bakthinian terms can be found in a June 2008 article in the Sunday Star Times.

Here, university lecturer Alison Jones discusses public reactions to her decision not to cover her bald head after chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer and her refusal to have a breast reconstruction or silicone-pad prosthesis after her mastectomy operation. Jones describes how people thought that wearing a wig "would make you feel normal", and the astonishment of the mastectomy bra-fitter when she requested a one-cup bra, who "had never heard of such a thing" (Jones 2008, 37).

All the prostheses are designed so that ‘no one would ever notice!’ Everyone can pretend you still have two breasts: in telling visual lies to each other, we can avoid literally facing the shocking loss that is not so uncommon (Jones 2008, 37).

Indeed, the pressure on Jones became so strong that she occasionally suppressed her desire to oppose society’s normative body image and wore a head scarf and silicone pad prosthesis to avoid unwelcome attention.

Much like Jones, many people with disabilities are seen as having "incomplete" bodies. The assumption is that when a body does not physically conform to the norm (however this is defined in any given society), any deviation should be covered over to give the illusion that it does, in fact, fit the ideal standard. Lennard Davis, a researcher in disability studies, points out that by acknowledging only whole, systematised bodies, people can ignore their own repressed fear of the ‘unwhole’ or ‘altered body’ (Davis 1997).

Indeed, both Jones and David point to a crucial psychological issue, namely that human beings often seek to construe their world in such a way as to afford protection from fear and angst, and that it is vital to this end that we are personally detached from the sight of things that potentially disturb our sensibilities. In our context, this means that only a conventionally beautiful, immaculate body maintains the normative, reassuring order.

It fulfils our desire for an aesthetic which projects a perfected human body while concurrently submerging the "real"—and, according to this perspective, "imperfect" and somewhat uncanny—image of the human being. Picnic, however, transgresses this logic: Initially, the piece demonstrates the restrictive view of disability which hides "grotesque" or "incomplete" bodies to give the illusion of a classic, complete human form.

But subsequently, the narrative deconstructs this image by painting an extremely positive picture of the performers’ diversity as they proudly dance in a large, colourful and open space.

The film, particularly its second section, has something of the character of a "freak show" or carnivalesque festivity. Freak shows developed in the US in the 1840s, consisting of "the formally organised exhibition of people with alleged and real physical, mental, or behavioural anomalies for amusement and profit" (Bogdan 1988 p 10).

Often associated with circuses, they captured the Victorian imagination and their profitability demonstrated the appeal of grotesque imagery to large audiences. They have been interpreted in ambivalent terms, as Rebecca Stern argues with reference to a famous Mexican-born woman called Julia Pastrana whose genetic condition caused excessive facial and body hair, and who was exhibited in the mid-nineteenth century as the ‘Ape’ or ‘Bear woman’ sensation.

On one hand, Pastrana can be seen, in more conventional scholarly terms, as a commodity whose physical difference validates the audience’s normalcy and confirms normative exclusionary ideologies. But going beyond common critical paradigms in disability studies, Stern claims that rather than merely being objectified and "othered" by mainstream culture, Pastrana was a part of that culture and incited "empathy with the disruptive body" and an "effort towards alliance, collaboration, and understanding" which "recognizes difference but neither fetishizes nor seeks to erase it" (Stern 2008, 204).

Daniel King and Matt Gibbons in Lighthouse, 2002. Photo: Todd Antony. Courtesy: Touch Compass.

Daniel King and Matt Gibbons in Lighthouse, 2002. Photo: Todd Antony. Courtesy: Touch Compass.Picnic references the freak show and carnival—which have in common their display of grotesque bodies—through a combination of quirky music, 19th-century circus-like costumes, early black and white cinema, and comical movement; engendering, as one critic puts it, impressions of a "bizarre Victorian garden party envisaged through the lens of Alice in Wonderlands sic looking glass, peopled by an eclectic mix of strange folk" (Hambrook 2009).

The first part of the film uses the alienation of everyday, mundane activities to create, for the viewer, a sense of estrangement from ordinary reality, akin to surrealism. A male dancer, for example, receives a sip of another performer’s drink as he holds his trunk off the ground by lodging his feet up against a wall, challenging the idea that there are "normal" ways of accomplishing everyday activities.

In the second part of the film, the dancers, clad in vibrant red costumes, are filmed parading from right to left on a wall against the backdrop of a blue sky which puts their bodies fully on display. No attempt is made to cover up the wheelchairs or the fact that some performers are missing limbs; indeed, arguably the viewers’ attention is drawn to this very fact, underscored by the performers’ clownesque and boisterous dancing.

While the work thus seems deliberately to promote a curious gaze, not to say voyeurism, it does so by dissolving the high-low, centre-margin dichotomies witnessed both in society and the arts, just as Bakhtin, in his analysis of carnival, attacks the social hierarchies in favour of a free mixture of opposites, high and low, serious and popular. The carnival, so Bakhtin claimed, was "the feast of becoming, change, and renewal. It was hostile to all that was immortalized and completed" (Bakhtin 1968, 10).

Likewise, Picnic casts off the Western cultural notion of a normative, perfected body and renounces the idealised remoteness promoted by much romantic and classical ballet whose stage is populated by unearthly creatures such as sylphs and fairies. The figures in Picnic are marked as earthly, human and "imperfect" (performing as they are mundane activities such as eating, drinking and sleeping). Yet the film avoids brutal realism by cleverly transcending the movement vocabulary through stylistic devices such as alienation. Moreover, it draws on popular entertainment forms; and yet clearly aims at making a high-brow art statement.

The film thus challenges binary thinking, instead promoting the fusion of previously separated categories, and decentres the normative body while vindicating disabled corporeality as part of mainstream contemporary dance culture. Allusions may furthermore be drawn between the destabilising of dichotomies in Picnic and the "universal" view of disability.

The universal model, promoted by researchers such as Bickenbach, Zola, and Price and Sheldrick, examines disability as an "identifiable variation of human functioning" (Bickenbach 1999, 1183) as opposed to the medical model which pits it as a point of difference against notions of normalcy. Universalising disablement means that disability and impairment are seen as fluid, continuous and context-based, and hence as a universal feature of the human condition. The renunciation of notions of embodiment as ‘stable identity categories’ (Shildrick 1998, 245) complicates the separation of individuals into oppositional binaries.

Consequently, this perspective on disability gives individuals the agency to shift beyond normalised expectations. It is, ultimately, the empowerment and liberation of the disabled person which Picnic brings to the fore through a refusal to comply with established categories of identity, perfection, and aesthetics.

Conclusion

People with disabilities have made a remarkable journey from being viewed as inferior, deviant and state-dependent to the disability pride festivals of today.

The changes brought about by New Zealand’s disability social movement in conjunction with the innovations of postmodern dance have opened up the world of performance to a much wider range of dancers. The fact that there are now professional integrated dance companies within the mainstream concert dance arena demonstrates the desire to challenge the hierarchical and exclusive foundations on which the Western dance tradition was built.

However, companies need to ensure that they do not reinforce common negative cultural representations and constructions of disabilities within their choreographies. Our discussion has shown that the subversion of "ablest" aesthetics and beliefs can be achieved through different types of performance strategies, including a rethinking of the works’ framing, the use of multiple layers of narratives, the guidance of the viewers’ gaze, the deliberate exaggeration of a dancer’s (dis)ability, and shock tactics.

In This Word Love there remain elements which promote distinctions and comparisons between the disabled and nondisabled dancers; but Picnic certainly does not adhere to classic aesthetics and no particular style of movement or bodily shape is held up as an ideal.

The chronological analysis of these performances has highlighted Touch Compass’s move toward multi-layered narratives and an increasing awareness of the importance of the ways in which disability is presented on stage. This includes attempts to show the transparency of boundaries surrounding apparently fixed or stable categories such as in Picnic.

This tendency seems to be continued in their work Harmonious Oddity (2008), in which one performer’s reality and his fantasy are fused in a mixed media performance. The company also seems to be taking greater risks in their efforts to dispel myths of disability, such as the belief that people with disabilities are asexual. Works such as Lighthouse, Lusi’s Eden and Harmonious Oddity show disabled dancers as being physically attracted to others and as sexually desirable.

Thus, it would appear that Touch Compass have become increasingly wise with age as their choreographies now show greater complexity and consideration for the on-stage representation of disability.

As regards the disability social movement’s demand for self-governance (Tennant 1996), it will be interesting to observe the emergence of professional dance groups that are founded and run by artistic directors, choreographers and dancers with disabilities.

Will there be a time, moreover, when major mainstream companies which have not traditionally employed disabled dancers, such as the Royal New Zealand Ballet, begin to do so? And will New Zealand tertiary dance programs become more accessible so as to train professional dancers for integrated companies? The same questions need to be asked about major ballet companies and tertiary dance programs in other nations. 4

Inclusion and integration at these levels would increase the variety of performance opportunities beyond Touch Compass and Jolt in New Zealand as these two companies are obviously limited in the number of dancers they can employ at any one time and in their performance opportunities. If the current trend continues and more disabled dancers enter the dance network in New Zealand and elsewhere, we anticipate that audiences will witness self-governance with the formation of a collective of disabled dancers.

It is, indeed, possible that integrated dance offers the next progression in the Western contemporary dance tradition of challenging previous dance eras and established aesthetics.

References

- 60 Minutes: Dancers with Wheels, 1998. [Television series] TVNZ, TV One, 24 May.

- Adair, C., 1992. Women and Dance: sylphs and sirens. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan.

- Albright, A.C., 1997. Choreographing Difference: the body and identity in contemporary dance. Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press.

- Albright, A.C., 1998. Strategic Abilities: negotiating the disabled body in dance. In Dills, A. & Cooper, A.A. ed., 2001. Moving History / Dancing Cultures: a dance history reader. Middletown, CT: Wesleyn University Press, 56 – 66.

- Anderson, P. & Kitchin, R., 2000. Disability, Space and Sexuality: access to family planning services. Social Science & Medicine, 51(8): 1163 – 1173.

- Attitude TV, 2009. Past Episodes: dancing with Suzanne Cowan. (You Tube video) [on line]. Episode 3, aired 22 March 2009. Available at: http://www.disabilitytv.com/past_episodes/shows/dancing_with_suzanne_cowan [Accessed 24 March 2010].

- Au, S., 1988. Ballet & Modern Dance. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Bakhtin, M. M., 1968. Rabelais and His World. Translated from Russian by Iswolsky, H. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press.

- Benjamin, A., 2002. Making an Entrance: theory and practice for disabled and non-disabled dancers. London; New York: Routledge.

- Bickenbach, J.E.Chatterji, S., Badley, E.M. & Üstün, T.B. 1999. Models of Disablement, Universalism and the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps. Social Science and Medicine 48 (9): 1173 – 1187.

- Bogdan, R. 1988. Freak Show: presenting human oddities for amusement and profit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bordwell, D. & Thompson, K. 2003. Narrative as a Formal System. In Film Art: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Cheu, J. Performing Disability, Problematizing Cure. In Sandahl, C. & Auslander, P., ed. 2005. Bodies in Commotion: Disability & Performance. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Davis, L.J. Nude Venuses, Medusa’s Body and Phantom Limbs: disability and visuality. In Mitchell D.T. & Snyder S.L., ed. 1997. The Body and Physical Difference: discourses of disability. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Foster, S., 1986. Reading Dancing: bodies and subjects in contemporary american dance. Berkeley; CA: University of California Press.

- Haller, B., Bruce, D. & Rahn, J., 2006. Media Labeling Versus the US Disability Community Identity: a study of shifting cultural language. Disability & Society, 21(1), 61 – 75. Available at IngentaConnect [Accessed 25 February 2009].

- Hambrook, C. 2009. 2009 Touch Compass: The Sleep of Reason begets Monsters. [accessed 3 March 2011].

- Hutchison, N. 2006. Disabling Beliefs? Impaired Embodiment in the Religious Tradition of the West. Body & Society 12 (4): 1 – 23.

- Inahara, M. 2009. This body which is not one: The body, femininity and disability. Body & Society 15 (1): 47 – 62.

- Jolt Dance, 2009. Jolt Mixed Ability Dance Company [Accessed 10 February 2009].

- Jones, A., 2008. Cancer Etiquette 101. Sunday Star Times: Sunday Magazine. 10 June, 37A.

- Kailes, J.I., 1985. Watch Your Language, Please! Journal of Rehabilitation, 51 (1).

- King, Y., 1993. The other body. Ms, 3 (5): 72.

- Kuppers, P., 2000. Accessible Education: aesthetics, bodies and disability. Research in Dance Education, 1 (2): 119 – 131.

- — 2003. Disability and Contemporary Performance: Bodies on Edge. London: Routledge.

- Longmore, PK., 1985. Screening Stereotypes: images of disabled people. Social Policy 16 (1): 31 – 37.

- Milligan, M.S. & Neufeldt, A.H., 2001. The Myth of Asexuality: a survey of social and empirical evidence. Sexuality and Disability, 19(2), 91 – 109. Available at: SpringerLink [Accessed 11 February 2009].

- Morrison, E. & Finklestein, V. Broken Arts and Cultural Repair: the role of culture in the empowerment of disabled people. In Swain, J., Finkelstein, V., French S. & Oliver, M., ed. 1993. Disabling Barriers Enabling Environments. London: SAGE Publications.

- Norden, M. F., 1994. The Cinema of Isolation: a history of physical disability in the movies. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Oliver, M., 1990. The Politics of Disablement. London: Macmillan Education.

- Powles, M., 2007. Touch Compass, Celebrating Integrated Dance. David Ling, Auckland. (See review by Sally Chance, Brolga, 30: 46 – 48).

- Sandahl, C. & Auslander, P. ed. 2005. Bodies in Commotion: Disability & Performance. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Shildrick, M. & Price, J., 1998. Vital Signs: feminist reconfigurations of the bio/logical body. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Smith, O. 2005 Shifting Apollo’s Frame: challenging the body aesthetic in theatre dance. In Sandahl, C. & Auslander, P. Bodies in Commotion: disability & performance. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Stern, R. 2008. Our Bear Woman, Ourselves: Affiliating with Julia Pastrana. In Marlene Tromp, ed. Victorian Freaks: The Social Context of Freakery in Britain. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State UP.

- Sucato, S., 2006. Dancing Wheels Review. Arts Air, 18 December. [Accessed 5 December 2008].

- Sullivan, M., 1995. Regulating the Anomalous Body in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Disability Studies, 1: 9 – 28.

- Tay, M., 2000. CandoCo Dance Company: in the company of able(d) dancers. The Flying Inkpot Theatre Reviews, 2 October. Available at: [Accessed 5 December 2008].

- Tennant, M., 1996. Disability in New Zealand: an historical survey. New Zealand Journal of Disability Studies, 2: 3 – 30.

- Tepper, M.S., 2000. Sexuality and Disability: the missing discourse of pleasure. Sexuality and Disability, 18 (4): 283 – 290.Available at: SpringerLink [Accessed 11 February 2009].

- Touch Compass Compilation: with full length version of 'Lighthouse', 2008. [Unpublished DVD recording] Auckland: Touch Compass Dance Trust.

- Touch Compass Compilation: see films, ‘Union’ or ‘Picnic’, (2008). [Unpublished DVD recording] Auckland: Touch Compass Dance Trust.

- Touch Compass Dance Trust, 2008. Past Productions: RESIN8'99 (company website). [Accessed 2 June 2009].

- Touch Compass Dance Trust, 2009. Mission Statement (company website). [Accessed 26 December 2010].

- Whatley, S., 2007. Dance and disability: the dancer, the viewer and the presumption of difference. Research in Dance Education, 8 (1): 5.

- World Health Organisation, 2000. ICIDH-2 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva, World Health Organisation..